By: Edward Spannaus

Did you know that Loudoun County is one of the few counties in the Commonwealth of Virginia that has retained its historic records intact? And, did you know that Loudoun is only one of two or three Virginia counties that has a separate archives division for public access?

These and other little-known facts were discussed on August 7, when Thomas Balch Library hosted Eric Larson, Loudoun County’s Historic Records Manager, for a presentation on “Making Loudoun’s Historic Records Available to the Public.”

Larson told how the County’s official records were preserved during the Civil War – a time when many counties’ records were destroyed or lost. On the eve of the war, the Justices (Judges) of the court ordered the then-Clerk, George K. Fox, to remove the most important records to a safe location. Fox, however, took all the records – not just those deemed most important – about 200 miles away to Campbell County, Virginia, which at that time included the city of Lynchburg. After the War, Fox brought the records back to Loudoun. Other nearby counties, such as Fairfax, were not so fortunate, and lost many of their old records.

Larson’s presentation (see the video here) discussed the types of records available at the courthouse, and the challenges in preserving these very old documents — which date back to the establishment of Loudoun County in 1757. He also went through the ongoing program to make more and more of these records accessible online, which we will discuss in more detail below.

Carrying out a vision

But first, let’s explore how Loudoun County managed to establish a separate Historic Records Division, and one with such extraordinary public access. To help in understanding this, I spoke with Gary Clemens, who has served as the Clerk of the Circuit Court for the past 25 years. Prior to being elected Clerk in 2000, Clemens had worked in the Fairfax County Circuit Court, where he became familiar with that county’s extensive collection of historic records – the largest in the Commonwealth of Virginia. And long before that, he had developed a passion for Virginia and Loudoun County history while a student at Loudoun Valley High School, under the inspiration of long-time history teacher Richard Gillespie (who is now a member of the Board of Directors of the Lovettsville Historical Society).

In Clemens’ early years as Clerk, his deputy clerk was John Fishback. At the time, Fishback was “wearing many hats,” as Clemens puts it, particularly carrying out courtroom duties. But when he had time – such as during his lunch hour – Fishback would undertake preservation and management of the County’s historic records. Clemens learned from Fishback that Loudoun – one of only five counties in Virginia that has its entire collection of historic records intact – had never had a full-time employee devoted to records preservation. The majority of the historic documents were locked up in cabinets, and were generally not accessible to the public.

In 2001, Clemens spoke to then-County Administrator Kirby Bowers, and explained how valuable the County’s historic records were. He urged Bowers to help with establishing a full-time position devoted to preservation of these irreplaceable records. Clemens then met with every member of the Board of Supervisors; he singles out then-Supervisor Mark Herring (like Clemens, a Loudoun native) as being particularly helpful. When the issue came before the full Board of Supervisors, the Board unanimously approved Clemens’ request for a full-time Preservation Manager to be included in the 2002-2003 County budget.

Naturally, John Fishback was appointed to this position. As the new Historic Records Division grew, it added a second, then a third, full-time staff position. This enabled the Division to apply for outside grants, to supplement taxpayer funding. The Library of Virginia provided major funding for preservation of records and improving public access, Clemens notes. The Ketoctin Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution has also made substantial donations for the preservation of Colonial-era and Revolutionary War records. Al Van Huyck provided funding for preservation of Road Cases and Slave records.

As a result of these efforts, Clemens says, he now tells people from other jurisdictions that “it’s really a museum for public records.”

“And that’s exactly what my vision was,” Clemens adds. This perspective includes public programs (such as a number of “First Friday” exhibits at the old Courthouse) to expand public awareness of the scope and uniqueness of the courthouse archives. “We want people to know that we have this really valuable museum of Loudoun history, manifested in the court records.”

Long after his retirement, John Fishback has continued to work — as a volunteer — three or four days a week on conservation of old records. Meanwhile, Clemens points out that Eric Larson, the current Historic Records Manager, has taken things to a whole new level – including the popular Loudoun history trading cards which were created during the Covid epidemic, and a number of informative brochures. With funding from the Board of Supervisors and outside sources such as the Library of Virginia, the Historic Records Division has now obtained some sophisticated equipment for preservation and scanning of archival records, which is enabling them to put more and more records online, where researchers and the public will be able to access them from their own homes and offices.

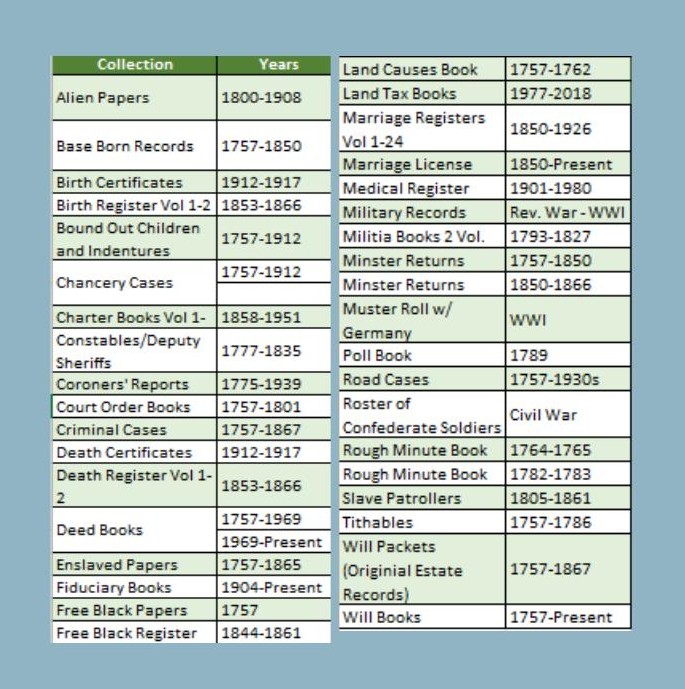

What kind of records does Loudoun have?

This would be good point at which to return to Larson’s August 7 presentation at the Balch Library.

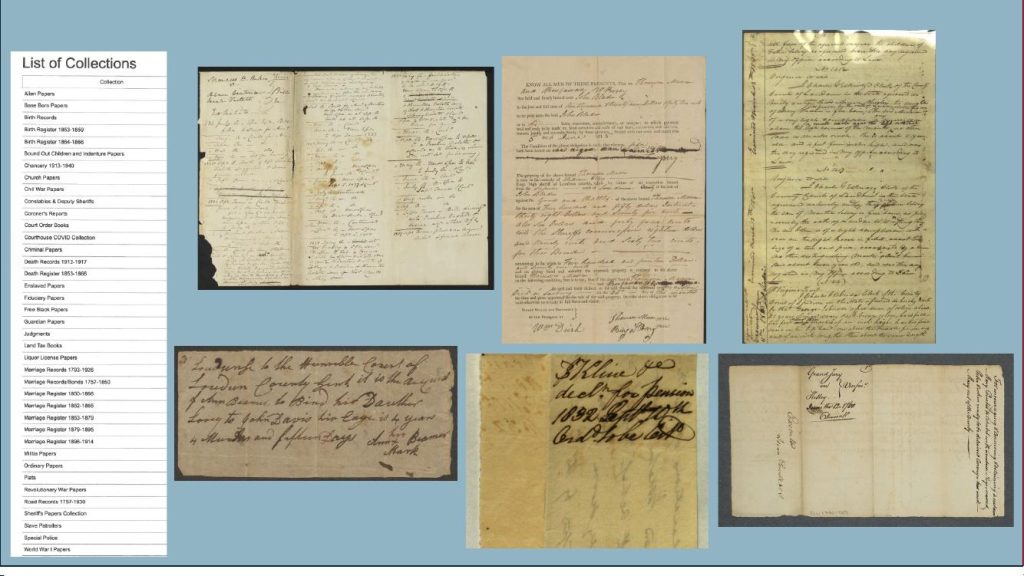

To understand what’s involved in preserving the court records, it’s helpful to know what format the records are in. The major categories are:

- Paper was the exclusive medium up until the mid-1980s. The so-called “loose papers” (unbound) are materials such as judgments and pleadings, which are maintained in packets or bundles, originally secured by red ribbon (or “red tape”). These documents are very small (paper was scarce in the old days), extremely fragile, and often have been damaged. They can be very difficult to read. (I made extensive use of these records during my research for the Tankerville series of articles which can be found on the LHS website.) In contrast to the “loose papers,” documents such as Court Orders, Wills, and Deeds are maintained in large bound volumes, which are stored on shelves in the Historic Records Division, to which the public has walk-in access.

- Microfilm and microfiche started being used in the mid-1980s. Although sometimes difficult to use, it enables the public to research records without repeated handling of extremely old and fragile materials. All these have now been scanned.

- The court went electronic in the late 1990s, and today, all new court records are created and filed digitally; paper records are no longer used.

- Online access is the latest innovation, Larsen said, which will involve making many more records available, through use of the “Past Perfect” software package. This is still a work in progress, and eventually will include many of the most interesting and sought-after records, such as civil and criminal court records, the “Free Negro” and Slave schedules, Tithables, and military (especially Revolutionary War) records.

The challenges being faced

When undertaking preservation of historic records, some of the problems encountered are:

- Damaged paper records, where pieces have broken off, or become illegible over time

- Insect damage

- Mold

- Earlier use of tape or glue

- Paper clips and staples

- Deteriorated leather bindings (“red rot”)

- Lamination

Anyone who has worked with bound records (Deeds, Wills, etc.) in the courthouse archives is familiar with lamination, a conservation process developed in the 1930s, in which thin sheets of acetate were melted onto each side of an historic document. In the 1980s, archivists began noticing that the laminate was breaking down, and sometimes gave off a vinegar-like smell. Subsequently, conservationists developed a delaminating process which is widely used today; after delamination and de-acidifying the original document, it is then placed in a Mylar sleeve.

While many of Loudoun’s bound record books needed to be sent out for conservation, John Fishback has been able to do some of this work in-house. Another of Fishback’s projects is taking the folded documents which have been maintained in judgment packets (sometimes for over 200 years), carefully processing them in a “spa” tank, and then opening and flattening them. This enables them to be maintained as “flat files” in conventional file folders so as to prevent further damage.

Professional digitization

As Larson explained, all Deed and Will books, as well as Tax books, have been scanned and are (or will be) available online — except for the Deed Books which require a subscription. Other record sets which have been scanned and digitized are those which are particularly used for historical and genealogical research, such as Alien Papers, Bound Out Children and Indentured, Slave Papers, Slave Patrollers, Marriage Licenses, and Will Books. (Some of these can be found here, others are not yet available to the public.)

Doing research with courthouse records

Larson said that he encourages those doing research to start at home, before coming in to the courthouse archives. This is because so much material, from indexes to full records, is now accessible online, and utilizing these resources gives a researcher a big head start in determining what’s available and where to find it.

The indexes on the Historical Records Division website provide guides to many sets of records:

- Criminal cases from 1757 to 1955 are indexed here.

- Chancery cases are indexed here; from 1757 to 1912 the indexes and full case files are available on the Library of Virginia website, which is linked from the Loudoun website. For 1913 to 1940, the indexes are on the Loudoun website, and most of the complete case files (now “flattened”) are available at the Historic Records Division. (Note: I have been using these Chancery case files for many years, and often find them a treasure-trove of previously-unknown information.)

- Deeds, Wills, and many Vital Records are indexed, with the original records available in many cases.

- Tax records are not yet indexed, but are available at the courthouse. These can be the only way of researching the age of a house, since they separate the value of the land and of improvements. A spike in the value of improvements indicates that a house or other structure has been added to the property. They also list the value of personal property, the category which included enslaved persons among other “property.”

- Court Order Books recorded every action taken by the courts up until 1904, including many actions which since 1868 would be taken by the Board of Supervisors. Larson described these Order Books as an “encyclopedia of the court system.”

- Specialty Order Books include orders regarding Free Negroes (the freeing of enslaved persons), Tithables (1757-1786), Guardianships, etc.

- Military records (found here) include the “Rough Minute Book” for 1782-83, which reports court orders during the last years of the Revolutionary War, such as reimbursement to citizens for provisions supplied to the Army during the Yorktown Campaign.

- “Loose Papers” (some, but not all, of which are indexed and scanned) are the original records behind the indexes, and include Chancery and Civil cases, Publication Orders (sometimes useful for house research), Enslaved and Free Black records, military-related records (including pension applications), Indentured and Bound Out, and criminal cases.

From this, you can get an idea of how many, and what kinds of, court records are accessible to the public. In researcher lingo, there are an endless number of “rabbit holes” just waiting for you to happily dive into.

And now, for those who have made it all the way through this article, your reward is the link to the digitized records in the Historic Records Online Access, which is still under construction, but is available to those with the link: https://loudouncourtarchives.catalogaccess.com/home