On March 11, about 40 people assembled at the Loudoun Museum to commemorate one of the most significant steps on our nation’s road to independence: Virginia’s establishment of its Committee of Correspondence, and its call for other colonies to do the same and thereby create an independent network of communication with her sister colonies.

The event was sponsored by the Sergeant Major John Champe Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution, in cooperation with the Loudoun County 250 Committee, which was formed last Fall to coordinate events and programs commemorating the 250th Anniversary of the American Revolution.

The keynote speaker was Nancy Spannaus, an author and a member of the Lovettsville Historical Society, who spoke on the significance of Virginia’s call for the Committees of Correspondence. The resolution adopted by the House of Burgesses was read by Edward Spannaus, Vice-President of the Lovettsville Historical Society (and President of the Sgt. Lawrence Everhart Chapter of the SAR in Frederick, Maryland).

The Loudoun County delegates to the 1773 House of Burgesses, Thomas Mason (brother of George), and Francis Peyton, and the role they played in the Burgesses, were discussed by Barry Schwoerer, Vice-President of the John Champe Chapter, SAR.

Below are Mrs. Spannaus’s presentation, the House of Burgesses’ Resolution establishing the Committee of Correspondence, read by Edward Spannaus, and Barry Schwoerer’s remarks on Loudoun County’s Burgesses.

The Establishment of the 12 March 1773 Virginia Committee of Correspondence

Presented by Nancy Spannaus

What we are commemorating today was a radical step toward American independence. For it was from this innocuous-sounding call for Committees of Correspondence that the disparate, even feuding, colonies moved to develop both alternate centers of local government, and the framework for a unified nation.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the Committees of Correspondence were the institution responsible for calling the First Continental Congress – and ultimately the Declaration of Independence itself.

But how did it come about? There had been moments of intercolonial cooperation before, the most successful being the Stamp Act Congress, which launched the campaign that killed the stamp tax in 1766. And from that effort came one of the most significant patriotic organizations leading into the Revolution, the Sons of Liberty. But that semi-secret organization had gone into something of a lull by the early 1770s. Something else was needed.

There were two triggers for the establishment of the Committees that I have identified, both sparked by the British government’s determination to assert its powers in an increasingly dictatorial manner. The first was an extraordinary event in Rhode Island in June of 1772 – the burning of the Gaspee. Provoked by what they saw as aggressive, unjust harassment of commercial vessels by British ships enforcing customs duties, a group of more than 50 Rhode Islanders grounded one of those ships and reduced it to ashes (the crew had been removed; no one was killed). The event was interpreted in London as an attack on the Crown – and the government’s response was to search out the perpetrators and send them to England to be tried for treason!

Over the fall and winter of 1772-73, the Crown initiated this process by sending a Commission of Inquiry to Rhode Island. No one had yet been charged or arrested, but tensions were rising. The British government’s decision was seen as a fundamental violation of the right to a jury trial within one’s own jurisdiction.

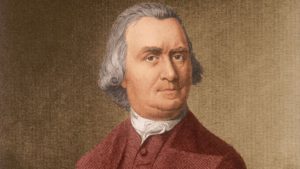

The second trigger was the Fall 1772 decision of the Crown to increasingly remove colonial power over their government officials in Massachusetts, by deciding to turn them into paid officers of the British government. The final straw was the decision to make judges British employees. What was the problem? This was the equivalent of having the judges paid by the prosecution! Patriots like Samuel Adams (a Son of Liberty) saw this as implementing a “system of slavery.”

After appealing to Governor Hutchinson to no avail, Sam Adams sprang into action, calling a session of the Boston Town Meeting on November 2. That meeting established a Committee of Correspondence of 21. On Nov. 20 the Committee presented an extensive resolution to the Boston meeting, which met with the meeting’s approval. The resolution was extensive – it asserted the colonists’ fundamental rights, itemized how they were being violated, and called for all the towns in the colony to join them in opposing the violations “as one Man.”

What was ground-breaking in this development? The Committee’s Resolution did NOT appeal for redress to the Governor or the Crown, but to their fellow citizens throughout the colony!

You could say that “We the people” were beginning to come into being, as the determinants of policy.

Even though this Committee of Correspondence structure was confined to Massachusetts towns, Adams and his colleagues ensured that the news and content of their Resolution spread throughout the colonies. They published a 36-page pamphlet on their proceedings and printed at least 600 copies. Newspaper coverage had appeared in New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Virginia by the end of 1772.

When he got the news, Thomas Jefferson said he felt “the foundations of government shaken under his feet,” and that the Resolution would have similar effects throughout all the colonies.

Also among those in Virginia who was alarmed at British violation of colonial rights was Richard Henry Lee, a leader in the House of Burgesses and one of the prime movers in the Stamp Act Revolt in Virginia. He wrote to Sam Adams seeking intelligence on the Gaspee affair in early February 1773, but didn’t wait for his answer to go into action. For when the House of Burgesses convened in early March, he joined with Patrick Henry (also a Son of Liberty), Jefferson, Henry Lighthorse Lee, and Dabney Carr in drafting the Virginia call for a continental network of Committees of Correspondence.

There was a local trigger for this action as well as the Rhode Island and Massachusetts affairs. Governor Dunmore had taken what threatened to be similar violation of rights through his arrest of alleged counterfeiters and removing them from their local community to the capital. An appeal by Patrick Henry for him to reverse this action met with contempt; it was that very night, March 11, that the small group of leaders met to draft the Virginia Resolution.

The next day, March 12, the full House of Burgesses unanimously adopted the Resolution, including the establishment of an 11-person committee to follow up. The resolution was immediately sent out to all the colonies.

The first colonies to respond were in New England. Rhode Island was first, followed by Massachusetts. As might be expected, the Boston Town Meeting received the call enthusiastically. It even issued a Broadside (leaflet) reproducing the letter sent by Richard Henry Lee and the full text of the Virginia resolution. Lee’s letter included the following statement of intent of the Virginia call:

To bring our sister colonies into the strictest union with us, that we may RESENT IN ONE BODY any steps that may be taken by administration to deprive ANY ONE OF US of the least particle of our rights and liberties. (emphasis in original)

The other colonies responded more slowly, but by March of 1774, all 13 had become part of the national network of communication that would serve as a nerve center for the Revolution.

What did the Committees of Correspondence actually do over the rest of 1773 and most of 1774? We know the Boston Committee was responsible for planning the Tea Party in December 1773. And with the British clampdown on Boston in March 1774, the Committees clearly went into high gear, increasing ties among the colonies, and creating the groundwork for the Resolutions that led to the First Continental Congress.

So, while we commemorate and celebrate the establishment of the Committees of Correspondence, I recommend that we, like they did, get to work by uncovering their activities. A review of local newspapers and the papers of leading members might be a good place to start. It was John Adams’ contention that the real revolution that occurred in the British American colonies was a revolution in the hearts and minds of the colonists, which took place long before the shooting began. Let’s uncover that revolution, starting today.

Resolution Adopted by the House of Burgesses

Read by Edward Spannaus

In the House of Burgesses, in Virginia, March 1773.

WHEREAS the minds of his Majesty’s faithful subjects in this colony have been much disturbed by various rumors and reports of proceedings tending to deprive them of their ancient, legal, and constitutional Rights;

and whereas the affairs of this Colony are frequently connected with those of Great Britain, as well as of the neighboring colonies, which renders a communication of Sentiments necessary; in order, therefore, to remove the uneasiness and to quiet the minds of the people, as well as for other good purposes above mentioned.

Be it resolved, That a standing committee of correspondence and inquiry be appointed, to consist of eleven persons, to-wit: the honorable Peyton Randolph, Esquire, Robert Carter Nicholas, Richard Bland, Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Harrison, Edmund Pendleton, Patrick Henry, Dudley Digges, Dabney Carr, Archibald Cary, and Thomas Jefferson, Esquires, any six of whom to be a committee, whose business it shall be to obtain the most early and authentic intelligence of all such Acts and Resolutions of the British Parliament or proceedings of administration as may relate to or affect the British Colonies in America; and to keep up and maintain a correspondence and communication with our sister Colonies respecting those important considerations and the result of such their proceedings from time to time to lay before this House.

Resolved, That it be an instruction to the said committee that they do without delay inform themselves particularly of the principles and authority on which was constituted a court of enquiry, said to have been lately held in Rhode Island, with powers to transport persons accused of offences committed in America to places beyond the seas to be tried.

Resolved, That the Speaker do transmit to the Speakers of the different Assemblies of the British Colonies on this Continent copies of the said Resolutions, and desire that they will lay them before their respective Assemblies and request them to appoint some person or persons of their respective bodies to communicate from time to time with the said committee.

The 1773 Loudoun County Burgesses

Presented by Barry Schwoerer

The question anyone may ask regarding the 12 March 1773 establishment of the Virginia Committee of Correspondence is: “how did the Committee involve Loudoun County?

The answer is twofold:

First, Loudoun County had two elected Burgesses representing the County when the Resolution to form the committee was approved on 12 March 1773.

Second, those same Burgesses, were responsible for taking reports from the Committee of Correspondence and communicating Committee reports to the citizens of Loudoun County.

Who were the two men?

Thomson Mason and Francis Peyton.

Both men are documented Patriots of the American Revolution, Mason for civilian Patriotic Service, and Peyton for both service as Colonel and civil Patriotic Service. Both men owned large tracts of land. Both men were slave owners. And both men were active in the establishment and operations of the early Governments of the Commonwealth of Virginia and the United States.

Thomson Mason was the brother of none other than George Mason, famous for the Virginia Bill of Rights and proprietor of Gunston Hall at Mason Neck.

Thomson was well educated, receiving a private education at home, then at William & Mary in Williamsburg, and finally at the Middle Temple in London, a college to train barristers, or lawyers. When he returned from England he was admitted to the bar and established a private law practice. He was elected as a Burgess representing Stafford County, and re-elected each year from 1766 to the early 1770’s. In 1760 he purchased a plantation in Loudoun County on the north side of Leesburg he called Raspberry Plain, and moved here in 1771. He was elected Burgess for Loudoun County for the 1772, 1773 and 1774 sessions. In 1778 he was appointed a member of the first Supreme Court for Virginia where he served a short while, and then was one of five judges of the General Court. In 1779 to 1783 he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates.

The mansion he built starting in 1771 was built by enslaved labor. At his death Thomson Mason owned 47 slaves.

His son, Stevens Thomson Mason served with distinction in the Revolutionary war as a Colonel and went on to serve as a United States Senator from Virginia.

Francis Peyton was born in 1733 in Prince William County to a prominent family. His father Colonel Valentine Peyton served in multiple county offices and was elected to the House of Burgesses. Francis was privately educated but did not get an advanced education. in 1755 he married Frances Dade in King George County. The couple settled in Loudoun County where Francis served as a Loudoun County Burgess from 1769 to 1775, the Virginia House of delegates in 1776 then 1780 to 1787. He was elected to the Virginia Senate representing Loudoun and Fauquier Counties from 1791-1811. Francis Peyton farmed using slave labor. In the 1787 Tax rolls he listed nine slaves under age 16 and ten adult slaves. He died late in 1815.

In summary, both Francis Peyton and Thomson Mason were large land owners, used slave labor, were respected in the community, were at the forefront of pre-revolution politics and were leaders in post-Declaration of Independence politics in Virginia.