A true short story

By the late 1940s, New Jerusalem Lutheran Church in Lovettsville was facing a problem. The old parsonage which stands behind the church cemetery had been built around 1832 – when New Jerusalem got its first full-time pastor. Upkeep and repairs were becoming very costly, and church officials began discussing whether they could sell it and build a new parsonage.

But there was a hitch. Sometime before the American Revolution, George William Fairfax, a land agent for Thomas, the Sixth Lord Fairfax, had given 12 acres of land to trustees of the German Lutheran Church in the German Settlement in Loudoun County. The grant of land was later confirmed by a deed dated October 20, 1797, which was executed by Ferdinando and Elizabeth Blair Fairfax for the purpose of “fulfilling the benevolent Intentions of their late Uncle George William Fairfax.” The 1797 deed stated that the land was granted “forever,” and for the purpose of erecting a church, a school, places of burial, etc.

However, the deed also said that if the land should cease to be employed for the church and related purposes, it would revert back to the Fairfax family – what was known as a “reversionary clause.” The church Council was concerned whether it had the right to sell any part of the property, since that might be seen to violate the terms of the land grant. So, on Sept 3, 1949, the Council asked Irvey Baker to find out if the Council could sell the parsonage and build a modern building.

Irvey Baker was the right man to do this. He had the best connections to the Courthouse crowd which ran Loudoun County: Baker had been the Supervisor for the Lovettsville District since 1931, and had been Chairman of the Board of Supervisors since 1943. This was quite remarkable, since the Lovettsville District was a political outlier in Democratic-controlled Loudoun County. Ever since the Civil War, Lovettsville had been the only district to consistently vote Republican I n national elections. Since running as a Republican in County elections might have been too much, Baker was elected and reelected twelve times as an Independent. An uncle of humorist Russell Baker, Supervisor Baker was popular in his district, and well-respected in the county.

In October, Baker reported back to the church Council, that he had gotten an opinion from Circuit Court Judge J. R .H. Alexander that the parsonage could not be sold because of the reversionary clause in the 1797 deed. In order to raise some money for the church, Fred Graham was authorized to rent out some of the parsonage land for pasture. But that didn’t solve the longer-term problem of what to do with the parsonage.

What was to be done? Irvey Baker apparently continued discussions with the judge and others, and on May 28, 1950, it was reported to a congregational meeting that Leesburg attorney Howard Vesey had come up with a way to remove the “cloud” over the church’s title to the land. Immediately, the congregation adopted a resolution authorizing the Council to sell part of the church property. Then things then began to move pretty fast.

Cloud, be gone!

What was the plan? It might seem pretty risky to us today, but somehow, they were pretty sure it would work. The plan was to have the Court appoint new Trustees, then go through the legal motions of looking for any heirs or descendants of the Fairfax family, and, if none were found, then “clear” the title by selling the church property at auction. The buyer would then have clear title to the property. But if it didn’t work out as planned, the congregation could lose the church building, the parsonage, and over 12 acres of land.

The next day, the lawyer Vesey filed a petition with the Chancery Court for the appointment of Trustees for New Jerusalem. An order was issued immediately, appointing three Trustees: Edgar Graham, P. F. Legard, and Irvey Baker.

A couple of days later, on June 2, a “Bill to Remove Cloud and Quiet Title to Real Estate” was filed in Chancery Court by Vesey. The case was styled Trustees of New Jerusalem Lutheran Church versus Ferdinando Fairfax et al.

Beginning on June 8, a legal notice seeking any Fairfax family heirs was published in the Loudoun Times-Mirror; the notice ran for consecutive weeks, and was also posted on the Court House door, and mailed to their last known address.

By December, when no heirs of the Fairfaxes had appeared, the Council was told that Judge Alexander would be making a final decision at next year’s term of the court, which begin in February.

In early April 1951, the plan to clear the title to the parsonage property was discussed in the Council, which instructed the Trustees to proceed with it. A week later, the Council decided not to upgrade the parsonage furnace to a newer type, but instead to just repair the old furnace; this was because the Council was planning on selling the parsonage once the title was cleared.

In early May, the Council was told that progress was being made on the title question – and indeed it was. On May 16 May, Judge Alexander appointed Albert F. Anderson (who was serving on the County Planning Commission at the time), as a Commissioner to take testimony in order to establish ownership of the property, and determine if a sale might be made.

Ten days later, three very brief depositions were taken of (1) Thomas B. Hutchison (the County’s deputy Commissioner of Revenue), C. S. Hutchison (the County Sheriff), and R. K. Gheen (the Assistant Cashier of Loudoun National Bank). Each, by coincidence it seems, said pretty much the same thing: that he was familiar with the New Jerusalem property, and would estimate the fair market value to be $500. Nothing was said about ownership of the property.

(The $500 figure seems reasonable. Assessed values for farmland in the area were upwards of $20 per acre at the time, which would put the value of the church’s land in the $250-300 range, to which must be added the value of the improvements such as the parsonage and the large brick church building.)

The Commissioner, Albert Anderson, submitted his report to the Court on July 9, 1951. He reported that: (1) the title to the church property was vested in the Trustees whom the Court had appointed in May 1950; (2) the value of the property was $500; and (3) a judicial sale could be made of a portion of the real estate for purposes of clearing title to the property.

It was reported to the Council in early September that a court order allowing the church to sell the parsonage in order to clear the title had been drafted, and was awaiting the judge’s signature.

Sure enough, on September 10 the Court appointed a Special Commissioner to sell a portion of the church real estate at public auction. The Special Commissioner was none other than Irvey Baker. Someone evidently had second thoughts about that, because four days later the Court issued a supplemental decree relieving Baker of his appointment, and appointing Carleton Penn II as Special Commissioner in place of Irvey Baker. (Penn was a local lawyer who had been serving on the County Planning Commission; by 1956 he was appointed a trial judge.)

The $50 auction

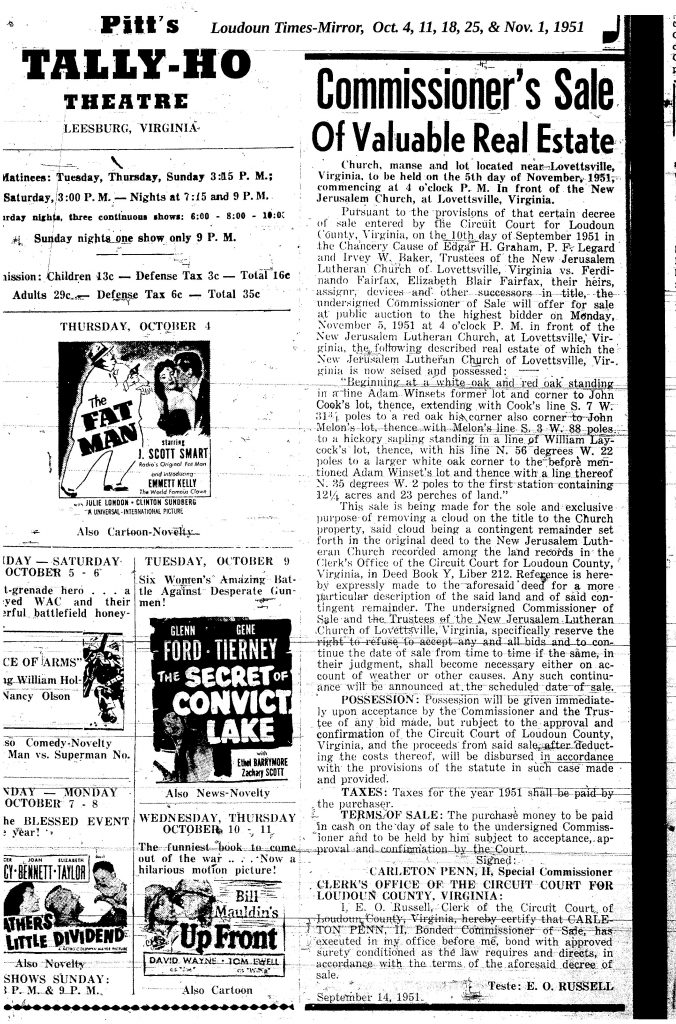

The plan was then put into action. For five weeks, from October 4 through November 1, a legal notice was published in the Loudoun Times-Mirror headlined: “Commissioner’s Sale of Valuable Real Estate,” stating: “Church, Manse and lot located near Lovettsville, Virginia, to be held on the 5th day of November, 1951, commencing at 4 o’clock P.M. in front of the New Jerusalem Lutheran Church, at Lovettsville, Virginia.” It was signed by Carleton Penn, II, Special Commissioner.

An auction of the church property – the entire property, not just the parsonage – was conducted in front of the church at 4:00 in the afternoon on November 5. 18 people were there. The highest – and probably the only – bid was for $50.00, and was made by Fred and Bernice Graham. For reasons not known to us, no one bid more than $50 for the 12-plus acres of land and buildings.

The church property was quickly transferred to the Grahams by means of a deed; and then the Grahams immediately transferred to property over to the three Church Trustees. All this was completed in time to be reported to the 7:00 p.m. Church Council that same evening.

According to Council minutes of November 5, “the parsonage property [sic] was offered for sale at Public Auction to clear the title. It was bid in for the Trustees by Fred Graham and his wife, deeded to them and immediately transferred back to the Trustees of the Church by Fred Graham and wife. The bid required to purchase it was $50.00.”

Six days later, on November 11, the deed to the church property, dated November 5, 1951) was officially recorded with the Clerk of the Court, conveying the church property from Fred and Bernice Graham to New Jerusalem Trustees Irvey Baker, P. F. Legard, and Edgar Graham. Even though the Church Council had always discussed the property to be sold as only the parsonage, what was actually auctioned off, and sold, was the entire original church property, the more than twelve acres, exactly as described in the 1797 deed from Ferdinando and Elizabeth Fairfax.

A month after the sale, the Special Commissioner Carlton Penn II submitted his report to the Court, stating that the church property was offered for sale at 4:00 p.m. on November 5 in front of the church by auctioneer Robert l. Wright; that 18 persons attended the sale; and that the highest bid was $50.00 by Fred and Bernice Graham. A week later, the Court issued an order approving the sale, and ordering the Commissioner to convey the deed to Fred Graham – which of course had been actually done five weeks earlier.

It might seem to us that this was a pretty risky scheme. What was to prevent somebody from showing up at the auction and outbidding the Grahams, with the unhappy result that the church could lose the church building, the parsonage, the old cemetery, and over 12 acres of land? Even if a bidder didn’t want the church building and the cemetery, the remaining land and the parsonage was still worth far more than $50! (In fact, less than two years later the back three acres alone was sold for $500.)

How could the Court, and the Church, be certain that no one other than an authorized representative of the church would bid on the property?

There was no need for the drama of a “penny auction” of the 1930s. For in this case, the Court had already declared that the church could refuse any bid. The public notice announcing the auction stated: “This sale is being made for the sole and exclusive purpose of removing a cloud on the title to the Church property, said cloud being a contingent remainder set forth in the original deed to the New Jerusalem Lutheran Church.”

The notice went on to state: “The undersigned Commissioner of Sale and the Trustees of the New Jerusalem Lutheran Church … specifically reserve the right to refuse to accept any and all bids and to continue the date of sale from time to time if … shall become necessary either on account of weather or other causes….” And further, the sale would still be subject to “the approval and confirmation of the Circuit Court of Loudoun County.”

We can only surmise that it was somehow made very clear that no one else would be allowed to bid on the property except a representative of the church. Otherwise, the venerable congregation could have lost everything that it had built and accumulated for almost 200 years.

And so it was, that New Jerusalem was bought and sold for fifty dollars – no more, no less — in what must have been one of the strangest public auctions ever to take place in Loudoun County.

–Edward Spannaus