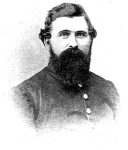

Captain Samuel C. Means, who commanded the Independent Loudoun Rangers during the Civil War, has finally received a U.S. government-issued headstone for his burial site, 138 years after his death in Washington D.C.

The headstone was dedicated on Saturday, March 26, 2022, at a ceremony at Rock Creek Cemetery held by the Lincoln-Cushing Camp of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW), the successor organization to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

The U.S.-issue headstone was obtained at the initiative of William Stump of the Augustus van Horne Ellis Camp of the SUVCW, located in New York State. Stump, who is also a Detective with the New York Police Department, has a strong interest in locating unmarked gravesites of Southern Unionist veterans, and during the ceremony he voiced his deep respect for those Southerners who remained loyal to the United States of America during the War of the Rebellion.

A special feature of the dedication ceremony was the participation of three direct descendants of Captain Means: Ron Deichmann and Rick Deichmann of Missouri, and Bob Deichmann of Florida. All three had travelled from their homes to be part of the headstone dedication.

Although they were nearly erased from Virginia history for many years, the Loudoun Rangers played a unique role during the Civil War, as the only Union military unit formed within the boundaries of present-day Virginia that served for the duration of the war. A biographical sketch of Samuel Means was presented at the ceremony by Lee Stone, a member of the Lincoln-Cushing Camp, and author of The Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers: A Roster of Virginia’s Only Union Cavalry Unit, published by the Waterford Foundation in 2016.[i]

Who was Sam Means?

Samuel Means, a prominent businessman in Waterford who owned and operated the large merchant mill on the west side of the village, was the founder and Commander of the Loudoun Rangers. Although there had been other attempts to form a partisan unit with Loudoun County, the War Department had declined those offers – including some from Means – until Secretary of War Edwin Stanton summoned Means to Washington in the Spring of 1862. In June, 1862 he was authorized to raise his own cavalry unit, which was to be independent of the normal chain of command. Means was mustered in at Harper’s Ferry later that month, and he immediately began recruiting volunteers from the Lovettsville and Waterford areas.

With weeks of receiving their uniforms, the Rangers, most of whom had little or no military experience, suffered heavy losses at the August 27 ambush at the Baptist Church in Waterford, and then again a week later in a skirmish north of Leesburg. A few days after that, they were ordered to Harper’s Ferry, where Means – who had a price on his head — was instrumental in organizing the cavalry breakout before the Union Commander surrendered his remaining forces to the Confederates.

For the duration of the war, the Loudoun Rangers served mainly along the Potomac border, often deploying on foraging or scouting raids, and guiding Union troops into Loudoun. Their orders took them to Ellicott City and the District of Columbia to the east, and occasionally into Berryville and the Shenandoah Valley to the west. They served until the end of the war, and were mustered out at Bolivar, near Harper’s Ferry, on May 31, 1865.

The turning point for Means came earlier, in March 1864, when the Rangers were ordered to report to Parkersville, WV on the Ohio River, and to be formally consolidated into the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry. The order came from the new Commander of the Department of West Virginia, General Franz Sigel. As Chamberlin and Souders put it, in their book Between Reb and Yank, “the former Prussian Minister of War [Sigel] had little inclination to permit an independent military unit to exist within his command….”[ii]

Seeing this order as a violation of the Secretary of War’s directive creating the Loudoun Rangers for special service along Loudoun’s northern border, Means and others refused, and Means was cashiered. Ultimately, Means was sustained by Secretary of War Stanton, who revoked Sigel’s order and confirmed that the Loudoun Rangers had “been recruited for conditional service.”

Despite having been discharged, Means stayed in contact with the military command and engaged in various scouts and forays into Loudoun, which has given rise to some speculation that Stanton’s failure to restore Means’s commission was so that he could be employed as a Union spy–although no evidence of this has been found.[iii] Indeed, he was still referred to as Captain in a March 1865 request from Gen. Stevenson to the Provost Marshall at Point of Rocks for a scouting party of Loudoun Rangers to go into Loudoun, and that “Capt. Means is to go with the party.”

Post-war life

Cautiously, Means returned to Waterford at war’s end in April 1865. Saddled by pre-war debts, he was forced to give up the Waterford Mill, his home on Bond Street, and other properties. He and his wife Rachel settled in at Bush Creek Mill north of Waterford; they lived there for ten years, but were unable to turn the mill into a successful business.

Means continued to be hounded by creditors, and he faced a hostile environment in the Loudoun court. As Chamberlin puts it, “there appears to have been a deliberate attempt to get back at the Loudoun Rangers’ captain and his brother.” This hostility was even clearer in lawsuits that Means and his brother Noble Means brought against those owing them money. “In almost all cases,” says Chamberlin, “the suits were continued indefinitely, or dismissed on technicalities, until the Means brothers finally abandoned their claims.”[iv]

One small political success was that Sam Means was appointed as superintendent of roads for his district in Lovettsville’s strongly-Republican township. The Lovettsville area was the most-heavily Republican jurisdiction in a county that was dominated by former secessionists in the post-war period.

Having been declared bankrupt and destitute, Sam Means and his family left Loudoun and moved to the northern section of Washington, D.C. in 1883, where Rachel operated a rooming house.

Sam died a year later, in 1884, at age 57, with the official death certificate listing cancer of the stomach and liver as the primary cause of death. He was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery, as were his wife Rachel and daughter Mary Alice in later years. For many years it was believed that his grave was unmarked, but about ten years ago a crude stone marker was found at the gravesite by Ann Belland, owner of the Samuel Means House in Waterford.

In 1892, Rachel Means was a special guest at a reunion of the Loudoun Rangers held at the Washington D.C. home of Lt. Luther Slater. As the GAR newspaper, the National Tribune, described it: “There they met their old Captain’s widow. Her kindness and sympathy manifested was very dear to the boys; all of them in the hour of trial, danger, and sickness, found through her sympathy, encouragement, and comfort. May her life be one of peace and happiness.”[v]

Rachel continued to run a boarding house in D.C. for many years, and she attempted on a number of occasions to obtain a widow’s pension, which was denied on various grounds including that of Sam’s discharge for disobedience. In 1897 she succeeded in getting a bill introduced in Congress by Rep. James A. Walker (R-VA), a former Confederate General who by this time was a Republican. Attached to the bill were several orders issued after Means’s dismissal, which upheld his position that the Rangers should not have been ordered to leave the Loudoun border area. Nonetheless, the bill was never passed by Congress.

It is thus proper and fitting, that Samuel Means, who sacrificed so much for his country, should at long last be recognized with a United States government grave marker at his final resting place.

–Edward Spannaus

[i] The following account of Sam Means’s life draws upon Mr. Stone’s outline (his remarks were extemporaneous, without a text), and also the following sources: Lee Stone, The Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers: A Roster of Virginia’s Only Union Cavalry Unit, Waterford Foundation (2016), “Forward” and “Appendix” by Edward Spannaus; Taylor Chamberlin and John Souders, Between Reb and Yank: a Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia, McFarland & Co., 2012; Taylor Chamberlin, “Captain Samuel Cornelius Means, Part 3: After the War,” Bulletin of the Loudoun County Historical Society, 2012.

[ii] Chamberlin and Souders, Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia, p. 235. For an evaluation of Means’s service, see p. 238.

[iii] Chamberlin, “Captain Samuel Cornelius Means, Part 3: After the War,” Bulletin of the Loudoun County Historical Society, 2012; available online at https://diversity-fairs-virginia.org/bulletin-of-loudoun-county-history/2012-edition-bulletin-of-the-loudoun-county-historical-society/

[iv] Ibid., pp. 12-13.

[v] Edward Spannaus, “Loudoun Ranger Reunions, 1890-1913,” Bulletin of Loudoun County History, 2020-2021 edition, p. 141.