By Lori Hinterleiter Kimball

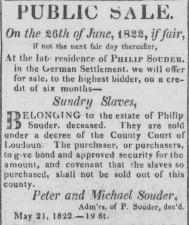

There are times when doing historical research that something – a person, an event, a reference – grabs the researcher’s attention and beckons to be investigated. Sometimes that work can start immediately and sometimes it has to be put on hold until time allows. For me, that attention-grabber was an 1822 advertisement in the Leesburg newspaper, The Genius of Liberty. “Sundry slaves for sale in the German Settlement” caught my eye while I was searching for advertisements related to a different project. Ads like this were placed frequently in local and regional newspapers, but it was the first I could recall seeing for Lovettsville. I wanted to learn more.

Phillip Souder (1760-1821) was a large property owner in the Lovettsville area. More specifically, he owned approximately 322 acres of farmland in the area known as Hoysville. As shown on the modern-day plat below, the largest parcel spanned present-day Lovettsville Road and was bordered by Quarter Branch Road, Downey Mill Road, Slater Road, and Tankerville Road. A smaller, adjacent parcel had Tankerville Road, Taylorstown Road, and Booth Road as three of its boundaries. Philip also owned 35 acres on the Catoctin Mountain. Known as wood lots, the timber was used for firewood, fencing, and other needs.[i]

Phillip Souder (1760-1821) was a large property owner in the Lovettsville area. More specifically, he owned approximately 322 acres of farmland in the area known as Hoysville. As shown on the modern-day plat below, the largest parcel spanned present-day Lovettsville Road and was bordered by Quarter Branch Road, Downey Mill Road, Slater Road, and Tankerville Road. A smaller, adjacent parcel had Tankerville Road, Taylorstown Road, and Booth Road as three of its boundaries. Philip also owned 35 acres on the Catoctin Mountain. Known as wood lots, the timber was used for firewood, fencing, and other needs.[i]

At the time of his death on 24 September 1821, the Souder family consisted of his wife Susannah Boger Souder and their nine children Peter, Michael, Mary, Catherine Elizabeth, Margaret, Anthony, John, Rachel Cost, and Susannah Cooper.[ii]

Philip died without a will, and two of his sons, Peter and Michael, were appointed by the court to oversee the affairs of his estate. In addition to his real estate holdings, Philip enslaved five people: Emanuel, Charles (also Charly), Betty and her infant child, and Mary Ann.[iii] Without a will, there was no clear direction for who should inherit Philip’s real and personal property and how it should be apportioned. To rectify this, the administrators of the estate and the heirs of Philip filed two chancery cases in the county court to have the estate divided equally among his heirs. This was not unusual when someone died without a will. A chancery cause was a suit of equity, meaning justices ruled on the basis of fairness, such as the equal division of land.

In these two causes, the land was ordered to be surveyed and subdivided so each heir would receive a share. The enslaved people were to be sold and the proceeds divided among the heirs. Peter and Michael were appointed commissioners to hold the sale, with 30 days’ notice to appear in the Leesburg newspapers, The Genius of Liberty and The Washingtonian. As shown in the ad, the auction was to take place on June 22nd at the Souder’s farm near the German Settlement.

The sale of the enslaved people was recorded at the courthouse on 26 June 1822. Emanuel had been sold to Philip’s brother-in-law John Slater for $450. Betty and her child were sold to Susanna Souder, Philip’s widow, for $350. Charles was sold to his daughter Margaret Souder for $251. Mary was sold to another daughter, Catherine Elizabeth Souder, for $250.[iv]

Note the requirement in the advertisement that the purchasers could not sell the enslaved people out of the county. That was a request impossible to enforce but it might indicate the Souder family’s hopes that the enslaved people would not be separated geographically. With three of the purchasers being immediate family members and John Slater a brother-in-law, it appears that the enslaved people remained with or near each other, at least initially.[v]

Philip’s daughter Margaret died two years after he did.[vi] Her will directed that the land she owned be sold and the proceeds divided between her brothers and sisters. She “gave” to her mother Susannah the enslaved “boy Charles who she bought at her father’s [estate] sale, paying and taking up the bond that she gave for him.”[vii] Susannah now enslaved Charles, Bet and her child, and any other children Bet had since 1822 as well as other enslaved people Susannah bought or inherited.

In the 1830 Federal Census, Susannah Souder was enumerated with the following in her household. The names in brackets are the author’s theory for who the people were.

1 white male between the ages of 20 & 29 [son John]

1 white female between the ages of 10 & 14 [unknown]

1 white female between the ages of 60 & 69 [herself]

1 enslaved male under the age of 10 [Charles?]

2 enslaved females under the age of 10 [Charlotte and Harriet?]

1 enslaved female between the ages of 24 & 35 [Bet?]

Susannah wrote her will in 1829, and she died in 1836. She was buried in St. James Reformed Cemetery where her husband was buried. Her will and estate documents provide further clues about the status of people enslaved by the family. She specified that her son John should inherit the 28 acres that she had purchased from Michael. The rest of her real estate was to be divided equally between her surviving children, Mary, Rachel, Peter, Anthony, Michael and Elizabeth. John was to inherit the enslaved boy Charles for a price of $275. The rest of the enslaved people were to be sold and the money divided equally among her children.

There was an approximate seven-year gap between the writing of the will and its submission to the county court on 12 April 1836. Enslaved boy Charles would have been a teen-ager by then. Her estate was inventoried and appraised 15 days later. Among the long list of household and farm items were the names of the people she enslaved:[viii]

- A negro woman Bet valued at $100.00

- 2 girls Harriet & Charlotte & Amos valued at $1000.00

The estate sale occurred the day after the inventory.[ix] One can imagine the fear and dread felt by the enslaved people as they awaited their fate. Harriet was sold to Mrs. Wire for $400.00.[x] Bet was sold to John Souder for $100.00. Charlotte and Amos were sold to John Souder for $300.00 and $200.00 respectively. The fate of the enslaved boy Charles, by then a teen-ager, was not documented in the estate records after Susannah’s death. It is possible that legal ownership passed directly to her son John as per her will, which might explain why Charles was not part of the estate inventory and sale.

In the 1840 Federal Census, John Souder was listed with the following in his household:

2 white males between the ages of 30 & 39 [himself & a brother?]

1 white female between the ages of 20 & 29 [wife Mary][xi]

1 enslaved male between the ages of 10 & 23 [Charles or Amos?]

1 enslaved female between the ages of 10 & 23 [Charlotte?]

1 enslaved female between the ages of 24 & 35 [Bet?]

Listed nearby was Elizabeth Wire with one enslaved female between the ages of 10 and 23.[xii] The person could have been Harriet.

The 1870 Federal Census is an important resource for researchers because it was the first time that formerly enslaved people were recorded by name. Without a last name to go on and assuming they might have stayed in the area, I searched the records in the Lovettsville area for people named Charlotte and Emanual. What a delight to find Emanuel and Charlotte Lickens living in or near the Hoysville area. He was 74 years-old with an occupation of laborer. She was 47 years old with an occupation of “keeping house.” Both were recorded as born in Virginia. Of course, this did not prove that they were the same people once enslaved by the Souder family nor did it establish their relationship – Husband and wife? Father and daughter? Brother and sister? I believed (but could not prove!) that they were the same people, and given their age difference, they were father and daughter.

Next up was the 1880 Census. A record was not found for Emanuel Lickens because he had died the year before. His death was recorded in the 1880 Mortality Schedule, listing his age as 90, his race as Black, cause of death as old age, and marital status as widowed.[xiii] There was no record of his wife living with him at the time of the 1870 census, probably indicating that she had died by then. It should be noted that marriages between enslaved people were not legal during the time of slavery, however enslaved people themselves, and sometimes the people who enslaved them, recognized the spiritual and family bond between them.[xiv]

Charlotte Lickens (spelled Scharlotte by the census taker), age 57, was found living in the household of Virginia and W.B. Lindsay and their family. Charlotte’s occupation was recorded as “servant.” Who were the Lindsays?

Mrs. Lindsay was the former Virginia Susan Souder, daughter of John and Mary Souder, and granddaughter of Philip and Susanna. John was the man who had purchased Bet, Charlotte, and Amos in 1836 from his mother’s estate. Mr. Lindsay was William Berry Lindsay, born in Kentucky to a mother who hailed from the Berrys of nearby Clarke County, Virginia. He was listed as a dentist in the census. The fact that Charlotte was living with a Souder family member strengthened the theory that she was the woman recorded decades ago in the estate papers of Susannah Souder. The Lindsay house still stands on Ropp Lane, about a quarter mile north of the lane’s intersection with Lovettsville Road.[xv]

Charlotte was not found in the 1900 Census, a possible indication that she had died by then. A search of Find-A-Grave located her place of burial and confirmed that she died on 24 November 1892. Her tombstone engraving identifies her date of birth as 25 March 1823, making her approximately 69 years old at the time of her death. Charlotte and Emanuel share a gravestone at St. James Reformed Cemetery in Lovettsville; they are the only Blacks known to be buried there. The engravings for Emanuel are birth date 28 May 1796 and death date 4 May 1880 (approximate age 83).[xvi]

Note the spelling of their name was Leekins, not Lickens as recorded in the two censuses. Still, missing pieces remained – their connection to the Souders family and their relationship to one another. That puzzle was solved by the obituary for Charlotte that was published on Friday, 9 December 1892, in The Brunswick Herald newspaper. An image from the newspaper and a transcription are shown below.[xvii]

The Mrs. Rodeffer in whose home Charlotte Leekins died was Mary Catherine Souder, daughter of John and Mary Souder and sister of Virginia Souder Lindsay. Mary Catherine was married to Mark Rodeffer. Charlotte’s age was listed as 60, which conflicts with her ages recorded in census records and on her tombstone. It is not unusual to find such discrepancies in earlier time periods, especially for formerly enslaved people for whom records are sparse. The same gospel verse was read at the funeral of Charlotte’s father, who most certainly was Emanuel. The big white house where Charlotte died – the Rodeffer homestead – still stands on the gravel section of Rodeffer Road.

The obituary confirmed the association with the Souder family and the relationship between Emanuel and Charlotte, but questions remain about their lives. I speculate that Bet, first mentioned in the 1822 chancery case, was the wife of Emanuel and mother of Charlotte. She might also be the mother of Mary Anne, Harriet, Charles (Charley), and/or Amos. The fact that Peter and Michael Souder wanted the purchasers of the enslaved people not to remove them from the county could indicate family ties and the Souder’s desire to keep them within geographic proximity to each other. Furthermore, John Souder purchased Bet, Charlotte, and Amos, possibly to keep the mother and children together.

Where were Emanuel and Charlotte born? Census records list Virginia, but that information is often incorrect. The last name of Leekins (or Leakins) is not common in Loudoun, however both Black and White people with the last name lived in Frederick County, Maryland.

My research will continue, and I will share new finds in future newsletters. In the meantime, please let us know if you have information about Charlotte or Emanual Leekins or any of the enslaved people discussed in this article.

Notes

[i] Loudoun County Deed Book (LCDB) 3F:198.

[ii] Philip’s heirs as of 1822 were identified in two chancery causes (Loudoun County Chancery Case 1822-006 and 1823-002) and the above referenced deed that divided the land. Son John was under the age of 21 when his father died. Daughter Rachel was married to John Cost. Daughter Susannah had married George Cooper, and they had a daughter (Margaret) Peggy under the age of 21. Susannah died in 1820, explaining why her daughter Peggy inherited her mother’s share of the estate. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/25613514/susanna-cooper. Philip and Susannah had a 10th child, a son named Philip who died in 1804. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/43473502/phillip-souder

[iii] LC Chancery Case 1822-006. Betty’s child was described as “her infant child now at the breast, unchristened.” Philip had purchased two enslaved girls, Delia and Betsey, from Abraham B.T. Mason in 1811 (LCDB 2O:197), and Bet was possibly Betsey.

[iv] Loudoun County Will Book O:83.

[v] John Slater was married to Catherine Souder, the sister of Philip Souder. Sources: Lovettsville Historical Society and Museum, Souder family records. Thomas Balch Library, Family File #160. Also, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/42947094/john-slater

[vi] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/43473609/margaret-e-souder. Also, her will (WB O:344) was submitted to the court on 12 January 1824.

[vii] LC Will Book O:344.

[viii] LC Will Book X:80.

[ix] LC Will Book X:94.

[x] Mrs. Wire was likely Catherine Elizabeth (Betsy) Wire who lived near the Souder family. 1840 and 1850 Federal Census records accessed on Ancestry.com. She married David Wire in 1824.

[xi] John married Mary M. Filler on 29 March 1837. Virginia, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1740-1850 accessed on Ancestry.com.

[xii] Her name was incorrectly indexed on Ancestry.com as Wein.

[xiii] U.S., Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850-1885 on Ancestry.com. 1880 Schedule for Emanuel Licken. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1877590:8756?_phsrc=VgV105&_phstart=successSource&gsfn=emanuel&gsln=licken&ml_rpos=1&queryId=77d3df67545bb160df6d0fa926e358c6

[xiv] Emanuel’s wife could have been living in a different household in 1870, especially if she was working in a domestic capacity, however the author found no evidence in the northern district census records. After freedom came, some formerly enslaved people recorded their earlier marriages at the courthouse; no record was found for Emanuel Leekins/Lickins. A death record was not found for a woman named Leekins/Lickens, which is not unusual, especially if she died while enslaved.

[xv] To read more about the Lindsey family, see Eugene M. Scheel’s Loudoun Discovered: Communities, Corners & Crossroads, Vol. 5, page 85.

[xvi] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/60101826/charlotte-leekins and https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/60101827/emanuel-leekins

[xvii] The newspaper image was graciously provided by Patricia B. Duncan. The transcription is from her book and used with her permission. Source: Patricia B. Duncan. Genealogical Abstracts from The Brunswick Herald, Brunswick, Maryland, 6 Mar 1891 to 28 Dec 1894. Willow Bend Books. 2003.