by Edward Spannaus, Board Member,

Lovettsville Historical Society & Museum

The Loudoun Rangers, a Union scouting and cavalry unit, were initially recruited mostly from Lovettsville and Waterford in the summer of 1862, during the Civil War. In his 1896 book The History of the Independent Loudoun Rangers, Briscoe Goodhart discussed an ill-fated attempt to expand the Loudoun Rangers in 1863. Goodhart reported:

What really happened to Capt. Patterson? Why did he disappear? No one ever knew for sure.Did he leave for greener pastures? Was he offered a better position in the Quartermaster Department? Or did some misfortune, something much worse, happen to him?

***********

We first learned of “Capt. Patterson” in Briscoe Goodhart’s The History of the the Independent Loudoun Rangers, in which Goodhart wrote:

The first effort put forth to recruit a battalion took tangible shape in the spring of 1863, while Company A was camped at Brunswick. Capt. Patterson, of Maryland, a former drillmaster of Company A (related to the Emperor Napoleon I. of France by marriage), was commissioned captain; Mr. Lovett, of Jefferson County, W. Va., was 1st lieutenant; William Bull was to be first sergeant. Recruiting offices were opened at Martinsburg, W. Va. There was issued to the company arms and uniforms for 50 men. Capt. Patterson was offered a better position in the Quartermaster Department. Lieut. Lovett became involved in some stock contracts, and the recruits, about 12 men, disbanded. The only one re-enlisted in Company A was William Bull. He came to Company A wearing first sergeant stripes. Although a private in Company A he was generally known as Sergt. Bull, or Patterson’s Bull.[i]

Much of the information presented by Goodhart (or, probably told by Patterson to various of the Loudoun Rangers) turns out to be wrong, to wit:

- Patterson was not from Maryland. He was born and raised in Florida, and was living in the City of Washington, D.C. before he enlisted.

- He was not related to Napoleon Bonaparte by marriage. This would likely have been through the family of Betsy Patterson of Baltimore, who was briefly married to Jerome Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother, but the marriage was annulled at the insistence of Napoleon, who offered Jerome the throne of Westphalia if he would leave Betsy;

- He did not go to the Quartermaster Department. When he disappeared from the Loudoun Rangers, it was because he had been captured at the Second Battle of Winchester, and he spent almost two years in Confederate prisons. He never recovered his health, and was debilitated for the rest of his life.

Patterson did make some significant contributions to the Loudoun Rangers, particularly in drilling, and in setting up their regimental books to conform to standard military practice. His story is an interesting one, revealed here for the first time.

Early Years

Fielding Patterson was born in 1837 at Key West, Florida. His father Alexander Patterson was Inspector of Customs, a politically-appointed position, in Key West. According to a later Senate report, Fielding “received a military education at one of the State institutions.” Around 1855-56 (when he would have been about age 18), his father arranged through U.S. Senator Stephen Mallory (D-Fla.) to get Fielding appointed to a clerk position with the U.S. Treasury Department, and he moved to Washington, D.C.

In 1857, in connection with the March 4 Inaugural Parade in Washington, Patterson was elected as the Assistant Marshall for Florida. In January of 1858 he married Mary S. Amiss, who also seems to have come from a fairly well-off family.

The War Years

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Fielding resigned from the Treasury Department, and in August 1861, he applied for a position in the Regular Army, bearing a letter of recommendation from Maj. Gen. M.C. Meigs, the Army’s Quartermaster General. (This connection might explain why Patterson told his comrades in the Loudoun Rangers in 1863 that he had an offer from the Quartermaster Department, and it might also explain why Goodhart thought that’s where he had gone, when he disappeared in June 1863.)

Instead of being appointed to the Quartermaster Department, he went to New York City and enrolled in the “Ira Harris Brigade” on August 27, 1861, and was mustered in as 1st Lieutenant in Company A, on September 12, 1861, for three years. The Ira Harris Brigade evolved into the 5th and 6th New York Cavalry, the 6th, being formed in November 1861. Patterson was carried on the rolls of the 6th NY Cavalry, under Col. Thomas Devin, on both the federal and New York State rosters.

The History of the Sixth New York Cavalry[ii], reprints a letter from Lt. Patterson to Col. Devin, dated 9 September 1862, from Trinity, Md., in which Patterson reports on a mission to determine the location of the rebels. The 6th NY was attached to Burnside’s 9th Army Corps during the Battle of Antietam; it remained encamped near Antietam Creek for eight days after the Battle. This is where the 6th NY was on Sept. 23, 1862, when Patterson submitted his resignation, and subsequently was honorably discharged, by order of Maj. Gen. Burnside.

We don’t know the circumstances of his resignation, but he seems to have gone, at some point, back to Washington, D.C. The next documented occurrence, is a Nov. 25, 1862, letter from Gov. F. H. Pierpont, Wheeling, Va., to “Capt. F. A. Patterson,” at Washington, D.C., stating:

You are hereby Authorized to raise a company of Cavalry (independent) for Scouting purposes in Fairfax and Louden and further south as soon as the Federal troops move in that direction — You will call on the proper departments in Washington Mustering officers and equipments — I desire you put on the same footing of Capt. Means.

This letter is apparently what Patterson referred to as his commission. The reference to “Capt. Means” reflects the fact that Capt. Sam Means of the Loudoun Rangers had been commissioned directly by the Secretary of War, and was authorized to raise an independent company.

To make sense of all this, it should be understood that the State of West Virginia regarded the Loudoun Rangers as a detached component of the 3rd W.Va. Cavalry. West Virginia records for its 3rd Cavalry Regiment list Samuel Means as Captain of Company F, “Permanently detached, Order Sec. Of War.” Daniel Keyes, who succeeded Means as Captain of the Loudoun Rangers, is likewise listed as a Lieutenant for detached Company F. The company which Patterson was authorized to recruit, was therefore designated as “Company G.”[iii]

According to post-war statements by Patterson, this is what happened next:

On the 25th Day of Nov. 1862, I was authorized by Gov. F. H. Pierpont then Gov. of West Virginia to raise a Company of Cavalry for the 3 Va. Cavy. I immediately at his request proceeded to Point of Rocks Md. and made it my Head Qrs. I found it difficult at that time to raise a Company and I set to work to assist Capt. S.C. Means their Commanding a Company of Independent Cavalry. I found his Company in very bad condition only 15 Men present but few of the Men had any equipments whatever there were but 10 Horses in the Company. I assisted him in organizing his Company drew Clothing Arms Camp and Garrison Equipage, and Horses. I made out all his requisitions and drew every thing necessary for his Company opened his Company Descriptive & Clothing Book also drilled his men, and got his Company up in proper trim. I remained with Capt. Means from 25 Nov 62 up to June 63, during the time I did military duty with his Company. I was always out scouting with them and very often Commanded his Company in his absence.[iv]

Another report, prepared by War Department investigators in connection with Patterson’s claim for pay, says that Patterson gave instruction to the Loudoun Ranger officers and drilled the men, explaining: “Capt Means & his officers never having studied or had experience in Military Tactics, while Patterson was educated at a Military School & served 18 mos. in the 6th N.Y. Cavalry.”

Meanwhile, both Gov. Pierpont and Sam Means were trying to get Patterson commissioned on the same independent basis as Means. On April 2, 1863, Means wrote to Secretary of War Stanton asking that Patterson be given the same commission as that provided to Means, and on April 13, Pierpont wrote to the Army’s Adjutant General, Brig. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas, asking for immediate attention to Capt. Patterson’s case. On April 23, in a letter from the Adjutant General’s Office to Gov. Pierpont, the requests were denied, stating that the authorization for Patterson to raise a company “cannot be given at this time.” As a consequence of this, the War Department in later years held that Patterson had never been mustered into Federal service after his resignation from the 6th NY Cavalry.

Back along the Potomac, according to the above-cited War Department report, Patterson — commissioned or not — commenced recruiting a company from Loudoun County, and as fast as the men were procured, they were mustered by Means and immediately put into Patterson’s Company (which would be what Goodhart refers to as the first attempt to form Company B). By the end of April, Patterson’s command was full, but he himself could not be mustered in, because Means was only authorized to muster enlisted men.

May-June 1863: Capture and Imprisonment

In one of Patterson’s post-war accounts, he said that he took sick in May and went home for a month, which probably meant to Washington, DC. In June, said Patterson, he left for Wheeling with some of his men to get mustered in, since Means could not muster officers. He only got as far as the Winchester area. According to his account:

After very hard work, I succeeded in raising a Company and was on my way to Wheeling to be mustered, but was prevented by the Enemy. Coming down the Valley and I was compelled with my Lieutenant to go into the fight without being mustered. I was captured at Winchester Va. June 15, 1863 and remained a Prisoner until March 1st 1865, a greater part of my Company was captured at the same time and since my imprisonment they have been put into other Companies and there remains no organization. After it was decided to evacuate Winchester on Saturday 14th June 1863, I was ordered to take charge of some Artillery and Team Horses to take them through the lines which I failed to do being knocked off my Horse by a Concussion of a shell. I was on duty night and day up to the time I was captured.

In another version, Patterson said that he and “his Lieutenants” were compelled to fight at Winchester without being mustered.

Goodhart’s account says that Patterson, Lt. Lovett, and Sgt. Bull were operating out of a recruiting office in Martinsburg – which is not far from Winchester. In the Second Battle of Winchester (June 13-15, 1863), Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell was moving down the Valley in what is now known as the Gettysburg Campaign (although no one at the time knew that the decisive battle in Lee’s second invasion of the North, would take place at Gettysburg.) On June 14, U.S. General Robert Milroy’s much smaller force had to retreat from Winchester, and they headed down the Valley Pike toward Martinsburg. On June 15, Ewell’s forces occupied Martinsburg, and Milroy’s forces evacuated to Harper’s Ferry. The action at Martinsburg is considered part of Second Winchester, so it is possible that Patterson and his men were at Martinsburg at the time.

According to War Department records, Patterson was taken prisoner on June 15. He was taken to Staunton, Va., then to Richmond, then to Danville, Va. and/or Macon, Ga. He was then confined at Camp Asylum, in Columbia S.C., and was paroled at N.E. Ferry, N.C. on March 1, 1865. He reported to Camp Parole near Annapolis, Md. on March 6. POW records list him both as a Captain of the 3rd Va. Cavalry, and as a “Citizen” – indicating that there was some doubt about his status.[v] He never fully recovered from his treatment in Confederate prisons.

Post-War

Patterson later said that he returned home after the War, very ill from hardship and exposure, and indeed he seems to be have been debilitated for the rest of his life. (He did not return to the service, either to the 3rd W.Va. Cavalry, or to the Loudoun Rangers—although the war was not yet over, and neither unit had yet been mustered out.) By April 4, 1865, while he was living at 400 D Street, in Washington, DC, he filed for his back pay from November 1862 through April 1865, with a statement concerning his service. A few days later, the War Dept. responded with a letter from the Adjutant General’s Office (AGO), advising Patterson that his name did not appear on the records of the 3rd Va. Cavalry, etc., and that no recruits were credited to him in Means’s Company.

In Patterson’s Volunteer Service file [vi] there is a long, undated handwritten report concerning his pay claim. It quotes from both his 4 Apr 65 letter and a second one of 12 Oct 65. The memo is entitled “Case of F.A. Patterson, who claims pay for services rendered as Capt. Co. G. 3rd Va. Cav. from Nov 25/62 to April 65.” The memo summarizes Patterson’s previous statements about how he was sent to Means’s company Independent Rangers, and how he help to reorganize and equip the company. (Parts of this memo were quoted above, regarding his activities at Point of Rocks.) As to his claims of having recruited a company, the memo states that no evidence can be found that Patterson enrolled any men for the 3rd Va. Cavalry regiment.

Apart from the bureaucratic incompetence of the report, one rather amusing “finding” is that “he states that he served the whole time in Means’s command … and always commanded in Means’s absence.” But, the report continues: “The rolls however of Means’s Co. covering this time … do not show that Means was absent at any time.” (In fact, it was well known that Means – who had a drinking problem – was often absent from camp).

The memo recounts what Patterson said about the circumstances of his capture and imprisonment, review his POW record, and concludes:

This case was before this office April 4-7/65 & it was decided that as Patterson’s name does not appear on any of the records of the 3rd Va. Cav. on file here and that the only Cos. of that regt (he claims Captaincy for G) that were mustered in 1863 were I & K – his claim for pay (as Capt.) could not be allowed upon the evidence presented.

An Adjutant General’s Office statement, dated 4 Nov 1865, possibly from Gen. Lorenzo Thomas, apparently refers to the above-cited memorandum, and seems to vindicate Patterson’s claims about his service – as well as making some disparaging comments about Sam Means:

This report has been carefully made out. It will be seen by it, that the gentleman cannot be mustered in to either Means, Atwell’s or any other company. I have no doubt that he performed all the duties that he claims to have performed. Means was wholly unfit to drill a company, or even a squad. He was simply a useful guide, or Scout. I see no way to help the claimant unless a special Act of Congress be passed for his relief. It is known that he was in the field, and exerted himself well during the time of Milroy’s command in the Valley, and it is quite possible he may have recruited the men he claims – but it is also possible that the actual captains of the respective companies would have them credited to themselves.

Being unable to obtain satisfaction from the War Department for his pay claim, Patterson managed to get a special bill passed by Congress. A report on his case was issued on Jan. 31, 1866 by the Senate Committee on Claims, which states:

It appears from the evidence in this case, that prior to the breaking out of the rebellion in the United States the petitioner received a military education at one of the State institutions, and just before the date of his commission held a position as a clerk in the United States Treasury Department. That he resigned the said clerkship to join the volunteer forces of the federal army, and was commissioned a captain in the 3rd Virginia Cavalry, by the Hon. F. H. Pierpoint, then governor of Virginia, on the 25th day of November, 1862. That during the winter of 1862, he was actively engaged, in connexion with Captain Means’s command, known as the Loudoun County Rangers, in arresting deserters and recruiting, drilling, and organizing volunteers. The during the winter of 1862, recruitments were stopped by the Secretary of War, and the men already recruited by the petitioner were turned over to said Captain Means, who mustered them into service as part of the Loudoun County Rangers. That during the Spring of 1863, recruitments were again commenced, and Captain Patterson immediately proceeded to Point of Rocks, Frederick County, Maryland, where his command was, to be mustered into the service, but found on reaching that place that the officer had only authority to muster enlisted men. That during the month of May, 1863, Captain Patterson was taken ill and obtained leave to visit his home, with a view to restore his health. That during the month of June, 1863, hearing of the advance of the enemy in Winchester, Virginia, he immediately repaired to the scene of action, joining his command, and assisting in the defence of that place. That on the 15th day of June, 1863, while engaged with the enemy, he, with his command, was taken prisoner and held as a captive from that time to the 1st day of March, 1865. It appears from the certificate of Brigadier General Hoffman, commissary general of prisoners, that F. A. Patterson, captain Company G, 3rd Virginia Cavalry, was taken prisoner at Winchester, Virginia, on the 15th day of June, 1863, and so held until the 1st day of March, 1865, when he was delivered on parole to the United States government at Wilmington, North Carolina; that he was declared exchanged by General Order No. 75, C.S.

It also appears from the certificate of C.W. White, major of the 3rd Virginia cavalry, that F.A. Patterson served as captain in said regiment, and was captured with him at Winchester, Virginia, on the 15th of June, 1863; that at the time Captain Patterson presented himself for muster with his men at Winchester, and afterwards, before said engagement, there was no mustering officer of the United States in that vicinity who was authorized to muster officers in the army.

It also appears from the certificate of C.L. Edmonds, captain 67th regiment Pennsylvania infantry, that F.A. Patterson served as captain of the 3rd Virginia cavalry, and was taken prisoner at Winchester on the 15th day of June, 1863.

It appears that the papers in this case were presented by Captain Patterson to the proper accounting officers of the government, and that he has not been paid for his services as captain for the reason that he was never formally mustered …

The special bill, “An Act for the Relief of F.A. Patterson, late Captain of the Third Virginia Cavalry” was passed by Congress on April 10, 1866; Patterson himself said it was passed at the request of President Andrew Johnson. It directed the Secretary of War to pay Capt. Patterson the full amount of pay and emoluments as a captain of the third Virginia cavalry from 25 Nov 1862 to the date of muster out of his regiment. Three days later, the Secretary directed the Paymaster of the War Department to make the payments to Patterson as specified in the bill.

Meanwhile, during early 1866, Patterson went back to work as a clerk in the U.S. Treasury Department for a short period of time.

1873 – 1888

There is no indication that Patterson was ever steadily employed after this. In the summer of 1873, he went to Staunton, Va, with his brother-in-law and his father-in-law. He returned to Washington the next Spring 1874, saying that his health was improved. In March 1877, he went to Illinois, but soon returned to Washington, with his health failing, and having suffered from one or more hemorrhages. The former Quartermaster of the 6th NY Cav., Capt. Hillman Hall, later filed an affidavit saying that he helped get a very feeble Patterson to Florida in 1877-78 in the hopes it would improve his health.

In May 1878, Patterson sent a letter to the Adjutant General’s Office, requesting that he be furnished with information on his capture at Winchester and imprisonment; this was in connection an application for a clerkship in the Treasury Department. He apparently was not successful in this, because the next year, he went to Pensacola, Florida. By 1881, he had become a Justice of the Peace in Escambria County, Florida, in western Florida panhandle.

Patterson’s wife Mary Amiss Patterson apparently did not go with him to Florida, because she died in Washington in April 1881, having been, for the previous year, a patient at the Government Hospital for the Insane, suffering from what was described as organic disease of brain. Mary is buried at Congressional Cemetery in Washington.

Patterson stayed in Pensacola until at least 1883. By 1885, he had returned to Key West, and by 1887 he was living in Rome, Georgia, in the northwest part of the state, about 60 miles south of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The Final Years

In the Spring of 1888, Patterson applied for an invalid pension. In June, he filed an affidavit from Rome, Georgia, in which he said that he had been confined to his room and bed for the past eight months, and that he had been unable to perform any manual labor for the previous ten years; in fact, he said, he had been unable to do any manual labor since he came out of Confederate prisons.

His problem was, that at this time, under the existing pension law, he could only apply for a disability pension, and the disability had to be incurred during war-time service. It wasn’t until June 27, 1890 that, under heavy lobbying pressure from the GAR, the law was changed so that the disability no longer had to be service-related, as long as the soldier had served for 90 days and had an honorable discharge. But when Patterson was applying, he could not prove that his disability was service related, due to the War Department’s inability to determine that he was in the service at the time of his capture and imprisonment. This arose from the confusion around his status as a recruiting officer, and the fact that he was “commissioned” by Gov. Pierpont, but was never mustered into the U.S. service as part of either the 3rd W. Va. Cavalry or the Loudoun Rangers.

In September, 1888, despite his debilitated and bed-ridden condition, he was married to Mary A. Williams, at Ringgold, Georgia (now part of the Chattanooga metropolitan area), where he went to live with her. By late 1888 he was living in Cleveland, Bradley County, Tennessee, about 25 miles from Ringgold. I was told by a local historian that Bradley County did not secede during the Civil War, and a Federal regiment was raised there, along with a larger number of Confederate regiments.

In a May 1889 letter apparently to the Pension Office, Patterson stated that when he was exchanged as a prisoner in March 1865, he “was very ill from hardship and exposure in prison,” and that he was for several months confined to his room with scurvy and chronic diarrhea:

I am now emaciated, worn down and exhausted, I am unable to answer questions accurately, as to dates and incidents. I am almost worn out. I am compelled to exclaim at times from the Depths of my heart, My God, My God, what shall I do. Privations staring me in the face. No money to buy medicine or clothing that I as much need as medicine is my dependence, if here is not enough evidence already in my case. I can give no more….

Patterson’s application for an invalid pension was met with the same obstacles as his earlier request for back pay, since his service in Virginia and West Virginia could not be documented. Although his service in New York was recognized, this was not sufficient, since his claim of disability arose from the period of his imprisonment, after he had been discharged from the 6th NY Cavalry, and when he said he was a Captain in the 3rd W.Va. Cavalry. His pension application was rejected in February 1890 – with the rejection being signed off on by Capt. Fred Ainsworth, Assistant Surgeon General and head of the Records and Pension Division, and approved by the Secretary of War. There was an element of either incompetence or vindictiveness in the rejection, which formally stated that, according to the Assistant Judge Advocate General of the Army:

“It appears by the summary herewith that F. A. Patterson raised his company by the authority of the Governor of Virginia, who after the company was raised, made an offer of its services to the United States Government which was declined, and that Patterson did not in fact become part of the military establishment of the United States by muster-in or otherwise…”

The rejection repeated the assertion that there was no such regiment as the “3rd Va. Cavalry” – apparently never considering that this could be referring to the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry.

Patterson then applied to Congress again, somehow getting a bill, S. 2644, recognizing him as captain of 3rd Va. Cavalry, introduced into the Senate in mid-February 1890. This was at the same time his application was being rejected by the War Department. (How someone who was living destitute in Georgia, was able to both retain a Washington lawyer, and get a private bill introduced into Congress, is a bit puzzling.)

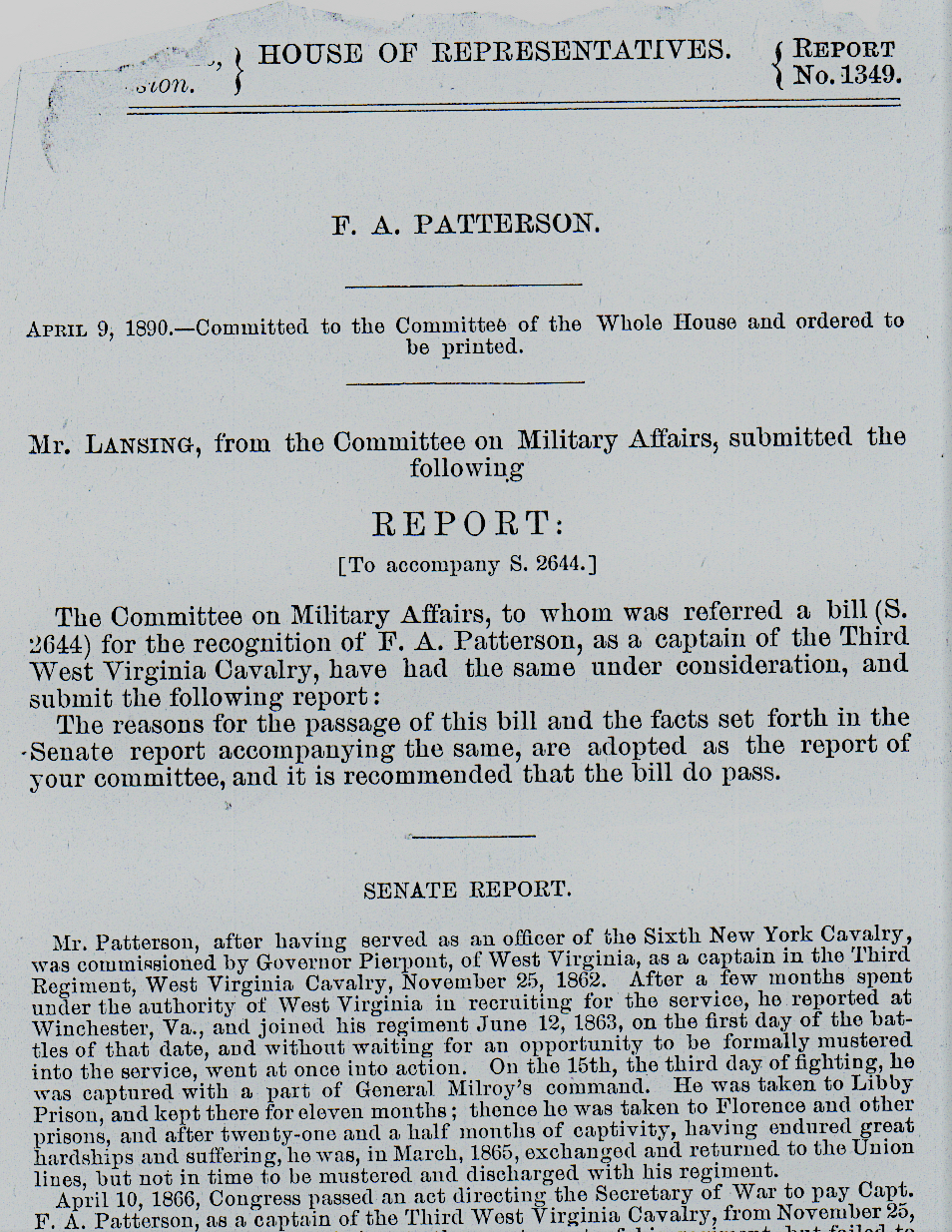

A Senate Report [vii] was issued on March 6, 1890, which described the facts in the case more-or-less accurately, as follows:

Mr. Patterson, after having served as an officer of the Sixth New York Cavalry, was commissioned by Gov. Pierpont of West Virginia, as a captain in the Third Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry, November 25, 1862. After a few months spent under the authority of West Virginia in recruiting for the service, he reported at Winchester, Va., and joined his regiment June 12, 1863, on the first day of the battles of that date, and without waiting for an opportunity to be formally mustered into the service, went at once into action. On the 15th, the third day of fighting, he was captured with a part of General Milroy’s command. He was taken to Libby Prison, and kept there for eleven months; thence he was taken to Florence and other prisons, and after twenty-one and a half months of captivity, having endured great hardships and suffering, he was, in March, 1865, exchanged and returned to the Union lines, but not in time to be mustered and discharged with his regiment.

April 10, 1866, Congress passed an act directing the Secretary of War to pay Capt. F.A. Patterson, as a captain of the Third West Virginia Cavalry, from November 25, 1862, the date of his commission, to the muster out of his regiment, but failed to direct that his name as such captain be entered upon the rolls of the regiment, wherefore he has not been paid. He has been an invalid since his discharge from prison, and is now confined to his bed and dependent upon charity, as his physician testifies. His wife is dead, and he has no children. His application for a pension has been rejected because he was not mustered before incurring his disability. It is a case of great hardship and conspicuousness.

A report was issued by House Committee on Military Affairs on April 9, 1890, incorporating the Senate Report, and recommending passage of S. 2644, for the recognition of F. A. Patterson as a captain of the Third West Virginia Cavalry.

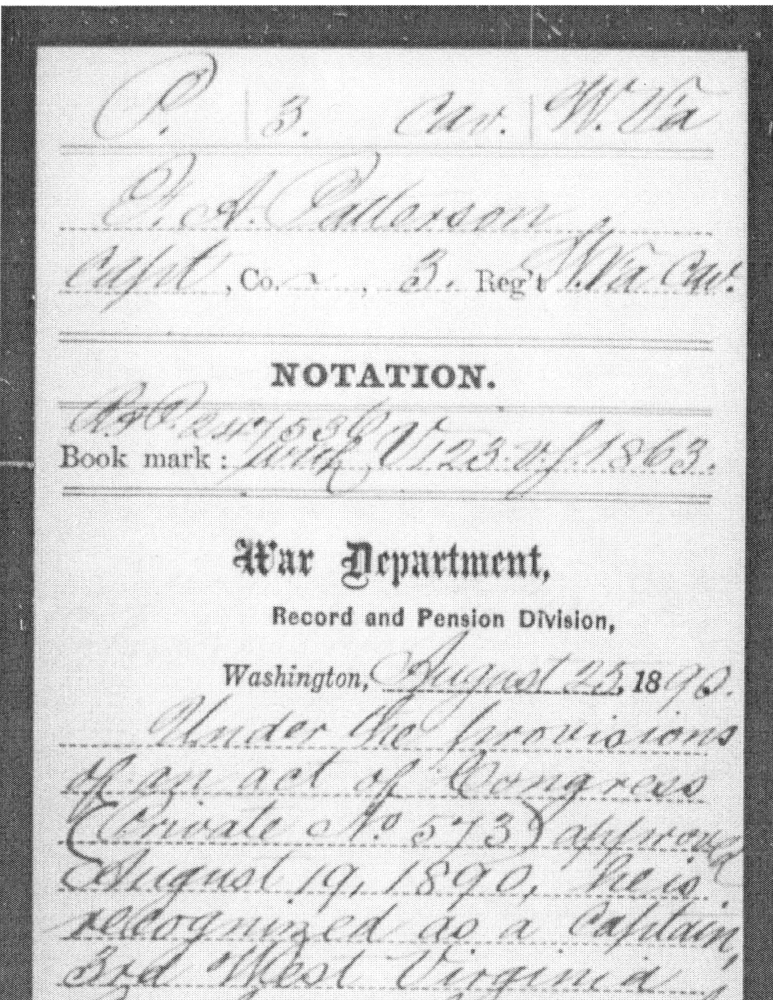

On August 19, 1890, Congress passed Private Act No. 573, recognizing Patterson as Capt. of 3rd W.Va. Cavalry Volunteers., from Nov. 25, 1862, the date of his commission, to the date of the muster-out of the regiment. Within a week the War Department’s Record and Pension Division acknowledged the bill’s passage, and amended its records to show that the Secretary of War was authorized and directed to recognize Patterson as a Captain.

Patterson apparently was immediately approved for a pension, because a little less than a month later, on Sept. 23, he filed for an increase in his pension. But he died a week later. According to a doctor’s affidavit, he died at his home near Cleveland, Tenn., on October 1, 1890.

Less than a month later, on Oct. 27, 1890, attorney George Clark of Washington filed an application on behalf of Patterson’s second wife for a widow’s pension. She was awarded a pension of $20/month, retroactive to October 2. She was apparently able to enjoy her pension for almost 40 years. Later censuses show her living at Villa Rica, in Carroll County, Georgia. She died in 1930, at almost 84 years of age.

Fielding and Mary Patterson are both buried in Concord United Methodist Cemetery, in Carrollton, Carroll County, Georgia. His headstone gives his date of death as Oct. 1, 1890; the inscription is: “My husband, Reverend F.A. Patterson, aged 53 years.” Her headstone reads: “Mary, wife of Rev. F.A. Patterson, Jan. 25, 1846, Jan.16, 1930, Faithful to her trust, Even unto death.”

Postscript:

Herein lies the last two puzzles: I have seen no reference in any of the records showing Patterson as a minister, but the standards for someone calling himself a minister were pretty loose, so it is possible.

Secondly, the popular Find-A-Grave website has a memorial for F.A. Patterson which states: “According to Known Confederate Burials of Carroll County Georgia 1861-1945, on file with West GA Library Special Collection: F.A. Patterson was a Private in Civil War … was in Company B, 56th Georgia Infantry.” No one with whom I have been in contact in Carroll County can explain this. There was no one by that name who served in the 56th Georgia Infantry, and the author of the cited book, Sam Pyle, a former SCV Commander told me that he doesn’t know why the book lists F.A. Patterson as a Confederate soldier; he thinks it may be a confusion with Pvt. Adam Patterson from Carroll County, who was in Co. B of the 56th Georgia Infantry.

See http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=83254952 and spouse link.

The volunteer who created the Find-A-Grave page for Patterson refuses to believe that Patterson was actually a Union officer, and not a Confederate soldier, despite my offer to provide documentation. This is not uncommon in those areas of the South which were once pockets of Unionism, but where Unionist history has since been erased.

* * * * *

Endnotes:

[i]

Briscoe Goodhart, The History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers, U.S. Vol. Cav. (Scouts), 1862-65. (Washington: McGill & Wallace, 1896,) p. 177.

Regarding the other recruiting officers mentioned by Goodhart: The “Lt. Lovett” to whom Goodhart refers, is apparently Lt. William E. Lovett of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry. Lovett was discharged as a private and mustered as a 2nd Lt. on Dec. 4, 1862. He was detailed as recruiting officer for Loudoun Rangers, Provisional Co. B, in the Spring of 1863. He was arrested in Frederick, Md. on 21 April 1863, while in a state of intoxication and saying this was an “abolition war” and he was “sick of fighting for the niggers.” He was imprisoned at Ft. McHenry; and was reported to be from Capt. Means’s Company, and to be threatening Means because of the arrest of Lovett’s brother, who was already in prison at Ft. McHenry. On 23 May 1863, Lovett was ordered to be discharged for disloyalty and conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. However it seems, according to Pension Office records, that this order was never carried out. He remained in the service, and was honorably discharged 4 Jan 1865, and mustered out 30 Jan 1865 at Wheeling.

Another recruiting officer in the Spring of 1863, not mentioned by Goodhart, was Lt. James W. Peery of the 3rd W. Va. Cavalry, detailed as recruiting officer for Loudoun Rangers in March-June 1863. WV Adjutant General records say he was promoted to fill the vacancy created by discharge of Lt. Luther W. Slater (a promising young officer who had resigned on account of wounds). In an affidavit dated 19 Jul 1884, Peery stated: “I was discharged as First Sergeant of my company `C’, 3rd W.Va. Cavalry, to accept a commission as 1st Lieutenant, in Co. `G’, commanded by Capt. Samuel Means. He claimed that his company was independent and did not belong to the 3rd W.Va. Cavalry. I was Commissioned by Governor Pierpont, then Governor of West Virginia. Means and the other officers were commissioned by the Secretary of War. I was ordered on recruiting service by Governor Pierpont, and remained on that duty until June, 1863.” In response to a letter from the Pension Office asking if he had ever served in Capt. Means’s Company, Peery replied that he was never mustered in to Capt. Means’s Company. He said he was commissioned by Gov. Pierpont, and that Means and his Lt. were commissioned by the Secretary of War, and that was the reason he could not serve in Means’s Company.

[ii] H. A. Hall, History of the Sixth New York Cavalry (Second Ira Harris Guard). (Worchester, Mass.: Blanchard Press, 1908), p. 20.

[iii] Theodore F. Lang, Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865. (Baltimore: Deutsch Publishing Co., 1895), pp. 194-196.

[iv] Handwritten statement by Patterson, dated April 4th, 1865, Washington City DC.

[v] A lengthy list of Union officers held as Confederate prisoners in Columbia, S.C. was published in the New York Times on Feb. 6, 1865; it listed Patterson’s unit as Co. G, 3rd Va. Cavalry.

[vi] Patterson Volunteer Service File, 123 VS 63, RG 94, NARA.

[vii] Senate Report No. 410, 51st Congress, 1st Session, from Mr. Hawley of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Senator Joseph R. Hawley of Connecticut, was a Civil War general, a leading Republican Party figure, and president of the United States Centennial Commission which organized the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia; he served in both the House and the Senate.

Support Our Mission

The Lovettsville Historical Society is a nonprofit organization that relies entirely on volunteer help. Support our mission to preserve and protect the history of Lovettsville, The German Settlement, and our unique corner of Loudoun County, Virginia. Purchase a membership or make a tax-deductible* donation today.

Visit us on the web at www.LovettsvilleHistoricalSociety.org.

Visit the Lovettsville Museum, open Saturdays 1:00-4:00 or by appointment, at 4 East Pennsylvania Avenue, next to Lovettsville Town Hall. GoogleMap It

Subscribe to our free monthly electronic Lovettsville History Magazine: http://lovettsvillehistoricalsociety.us8.list-manage2.com/s…

Join us and support our mission to preserve local history. https://squareup.com/store/lovettsville-museum/

* The Lovettsville Historical Society, Inc. is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization under the Internal Revenue Code. Contributions and membership dues are tax deductible under Internal Revenue Code Section 170.