Article originally published on February 18, 2016 by The Brunswick Citizen. Reprinted with permission.

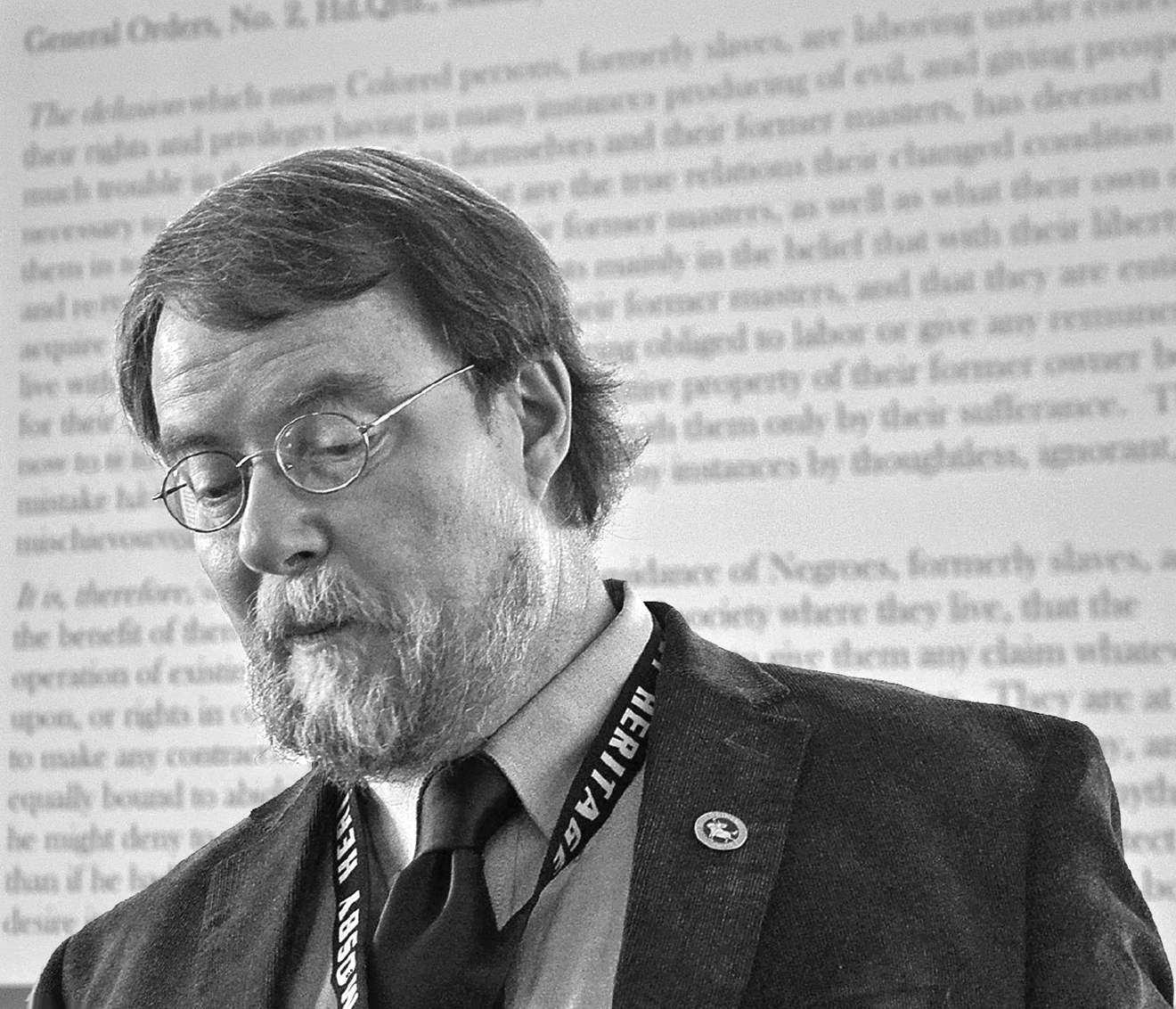

On Sunday, [Feb. 14, 2016], Richard Gillespie, [then] Executive Director of the Mosby Heritage Area Association, caused the St. James Church in Lovettsville, Virginia to fill up with eager listeners. Parked cars lined up and down the nearby streets, their occupants inside the church to hear Richard tell what it was like the morning after President Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC.Ed Spannaus, the Vice President of the Lovettsville Historical Society, introduced Richard, who the spoke about the change, the terrible resistance and the uncertainty that came after the Civil War ended and after President Lincoln was assassinated.

This was a sixth in a series of talks that Richard has delivered, with ever larger audiences each time. The premise of his most recent talk was this: “If we want to understand the history of a region, its the historical sites that allow us to tell the story.”

Drawing on a tradition of Native Americans who mark paths to spur stories about past events, Richard said, the monuments and places we have preserved” enable us to remember, and to pass on.” To sum it up, Richard said, it was a difficult adaptation we had to make after the war.”

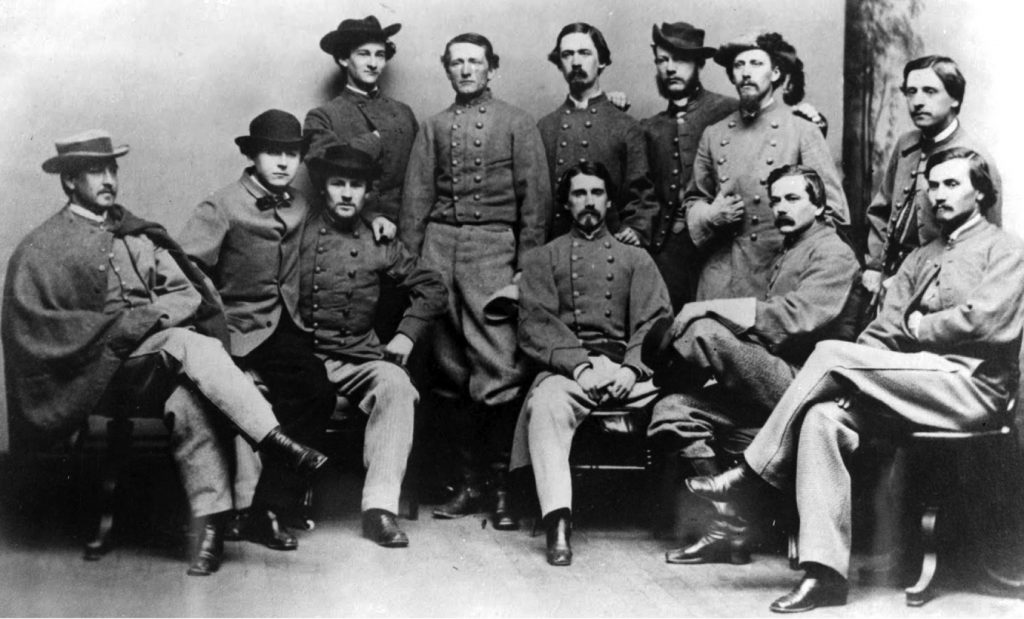

On March 1, 1862, Lovettsville saw its first Confederate soldiers. Fast forward to 1865, when Mosby’s Rangers attacked the Loudoun Rangers, annihilating them just three days before Appomattox and thus just before the end of the Civil War.

Even how they got from one place to another had changed by the war. The Berlin Bridge, connecting Lovettsville to Maryland, was down and, as Richard observed, “somewhat like today, it was not going to be repaired until 1898, 33 years after the war.”

The mills that had been so prosperous, producing grain for the nation, were destroyed in Union troop fires in 1864. Lovettsville escaped that wrath and the burning, Richard said, “perhaps because the Union troops expected to bivouac in the area.”

“Who’s the coward now?”

Massive numbers of soldiers on both sides had been physically injured and emotionally damaged, and, until after the war, there hadn’t been much time for funerals.

It was hard for men who had been friends, who had schooled and played together, gone to dances together, to return home, after the war.

Later diary entries suggest Frank Myers’ condition was what might have then been called “shell shock,” but that we now call PTSD. In one entry he wrote that “sleep has been a stranger to my eyes,” and he says also, “if memory would leave me, I’d be glad.” In still another, Frank said, he wasn’t “capable of taking care” of himself.

Frank Myers still thought he might fight but instead he went to Woodgrove, surrendered and “got the parole,” meaning he could go about his business, his citizenship and voting rights restored.

Frank had remorse shortly after he had his parole, writing, “I’m so sorry I surrendered.”

Elijah J. White, Lieutenant Colonel, in the 35th Virginia Battalion Brigade, said, “All who take the parole are traitors.”

On May 12, 1865, after Col. White got a parole, Frank asked, “Who’s the coward now?”

Union after the War?

At the end of the war, when slaves were freed, the question was how would they go on, and their former masters had the same question. There was a rumor that former slaves had 40 acres and a mule coming their way. But it wasn’t true.

There was going to be a general confiscation of property from public officials of the Confederacy. For example, Oatlands south of Leesburg was to be taken, but pleas from wealthy Loudoun homeowners to Washington succeeded in beating back the confiscation effort.

Mosby resisted surrendering until he saw there was no way to continue the fight, and there was even a bounty on his head, but, in the end, President Ulysses S. Grant paroled him.

Many of the injured had to raise funds for prosthetics for legs and arms.

Vice President Andrew Johnson, the Southerner who succeeded Lincoln, abolished Lincoln’s bill to help African-Americans to adjust after the war by establishing freedmen bureaus. Johnson believed that the bureaus encroached on states’ rights and prevented freed slaves from becoming independent by offering too much assistance.

There were schools created by men and women of courage, white and black, to teach African Americans; and there were threats against those who did so. Indeed, Virginia wouldn’t create a public school system until 1882.

When Union horses were sold, Confederates were careful to get papers for the horses they bought lest they be accused of stealing them.

There’s a romantic view that after the war, union followed. In fact, it took sixty years, Richard said, “to get to co-arguing at the Waterford store, and banging canes for emphasis.”

How two sides with such differences can ever get along is a topic that still resonates today. Richard apologized for talking so long, but no one noticed the time passing.

TOP: Historian Richard Gillespie discussing what it was like in Loudoun County, Virginia in 1865, when the Civil War ended. Photo by John Flannery.

Article originally published on February 18, 2016 by the Brunswick Citizen. Reprinted with permission.