By Edward Spannaus

For some years, I have been puzzled by the oft-repeated story of Lovettsville’s John Axline in the Revolutionary War: that he alternately served in Lt. Col. Posey’s Battalion of the 3rd Virginia Regiment, and went home to manufacture gunpowder for the Continental Army, and that, as a consequence of this, the British Army raided his house and terrorized his wife. (This story is found, for example, on page 18 of Lovettsville: The German Settlement.)

What is confusing about this, is that the British Army was nowhere near Loudoun County during the Revolutionary War, this being a highly-patriotic frontier area. Unless they were moving in large numbers, British soldiers stayed close to the Loyalist areas on the eastern seaboard. But Axline had moved to this area before the War, and he served in a Virginia regiment. Moreover, there was no gunpowder manufacturing in this area, as far as I know.

So how to explain the story of John Axline?

Answer:

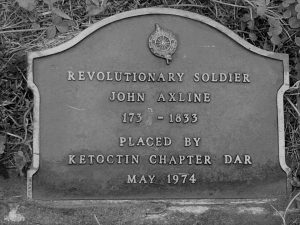

John Axline was born as Johannes Oeschlein in 1739 in Chester County, Pennsylvania, the son of George Christian Oeschlein who had emigrated from Alsace to Philadelphia in 1727. Around 1770, Johannes and his older brother Adam came to Loudoun County, to the area then known as the “German Settlement.” The brothers acquired property on what is today known as Axline Road, part of which today is the site of Hiddencroft Vineyards.

Adam later moved to Bedford County, Pennsylvania, and a number of John’s children later moved to Ohio. The family name was Anglicized as “Exlein,” “Exline,” and “Axline;” local church records spell it all those ways for the same families.

I found that a grandson of John Axline, Gen. Henry A. Axline (1848-1914) of Columbus, Ohio, had done a lot of research on his grandfather’s military service. Gen. Axline was known as the “Father of the Ohio National Guard,” having served as its Adjutant General for many years. Henry reportedly found Revolutionary War payroll records in which there was a notation “for special services” next to John’s name.

Later, this Henry Axline found an old chest which contained a diary kept by John’s wife Christena, in which she had written: “Everything is in confusion around me. Since John made the last gunpowder, the British have confiscated everything we have.”

Henry Axline then searched the Army supply records, and found a record of the gunpowder that John had made. Out of this, the story grew up that John would fight for a time in the Continental Army, and then go home and make gunpowder, then go out and fight again.

The Centennial History of Columbus, and Franklin Co., Ohio, by William Alexander Taylor, contains a biographical sketch of Gen. Henry A. Axline, which includes the following:

On the paternal side he [Henry] comes of Prussian ancestry. His great-grandfather, Christopher Axline, was a native of Prussia and served with distinction in the Prussian cavalry under Frederick the Great. While the United States was still numbered among the colonial possessions of Great Britain he came to America and during the period of the Revolutionary war engaged in the production of nitre for the manufacture of gunpowder for the American troops. In consequence of this, his property was confiscated by the British. His son, John Axline, removed to Loudoun County, Virginia, where he died in 1832 at the age of ninety-three years. He was the first settler of this family in that county. He was born in 1739 and was a farmer by occupation. He served as a captain in the Virginia line in the Revolutionary war.

The biographical sketch says that John’s family included Henry, born 1788, who removed to Ohio. He would be the father of Gen. Henry Axline. Now, this sketch is a second-hand account, and is clearly somewhat confused, since Christoff/Christopher died in 1768, and thus could not have made gunpowder during the Revolutionary War and had his property confiscated by the British. But Christoff’s son John Axline could have done this – and it seems highly probable that this would have been done near his father’s home, in Chester County, Pa., and not in Loudoun County, Va.

Pennsylvania gunpowder mills

Pennsylvania was the center of gunpowder manufacture, at least in the early years of the war; Virginia was not.

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, there were only three gunpowder mills available to the Continental Army – two in southeastern Pennsylvania, and one near Morristown, New Jersey. Additional mills were then established in New York State, Connecticut, and Massachusetts.

Although by early 1776 there were a number of gunpowder mills operating in the area around Philadelphia, the Committee of Safety of Pennsylvania wasn’t satisfied, and so, with the approval of the Continental Congress, it authorized the creation of the first state-funded and state-operated gunpowder mill in the colonies. This was a Continental Powder Mill, on French Creek in Pikeland Township in Chester County.

Pikeland Township is precisely where Christoff Axline and his sons Adam and John were living at the time of Christoff’s death in 1768.

In December 1776, British raids forced the removal of the powder and military supplies from French Creek to Lancaster; after the threat blew over, manufacturing was resumed at French Creek with a company of militia stationed there. In March 1777 an explosion ended production at French Creek. Three others mills went out of production by the end of that year, leaving five mills operating in southeast Pennsylvania.

The mills which kept operating in southeast Pennsylvania up to the end of the war (which would be relevant if we are talking about John Axline making gunpowder as late as 1782) were Oswald Eve’s mill in Frankford, just north of Philadelphia, Lorch’s mill in Philadelphia County, and Lush’s mill in Norriton, near King of Prussia and Valley Forge, in Montgomery County. (The latter location is close to where John’s older brother George was married and lived for a while, before going to live near his father in Chester County.)

John Axline’s military service

The military service records that I found for John are:

- Index card (created late 19th century from the original records) for “John Exline, Virginia Battalion Composed of Companies of various Reg’ts,” listed as a “Private.”

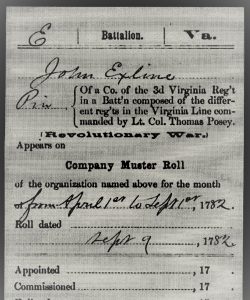

- Index card for John Exline, “of the 3d Virginia Reg’t in a Batt’n composed of the different reg’ts in the Virginia Line commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas Posey.” Company Muster Roll dated April 16, 1782; term of enlistment 6 months.

- A similar index card for a Company Muster Roll index card for April 1 to Sept. 1, 1782, roll dated Sept. 9, 1782; term of enlistment 41 days.

- Another index card for “John Exline, Sol. Inf.” “Appears in a Book under the following heading: `A List of Soldiers of the Virginia Line on Continental Establishment who have received Certificates for the balance of there [sic] full pay Agreeable to an Act of Assembly passed November Session 1781.’” Dated Sept. 15, 1784, for Sum of ₤16-19.

- Copy of original “Muster of a Company of the 3d Virginia Regiment in a Battalion composed of the different Regiments of the Virginia Line – commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas Posey.” Listed as a Private is John Exline; term of enlistment is 6 months. It is dated April 1st, 1782. On the back it is identified as “Muster Roll of the Company of the 3d Virg. Regt. Col Posey’s Detachment [?] Sept. 1782. From 1 April to 1 Sept 1782. (Listed on this same Muster Roll are John Roller and Conrad Roller, brothers who are documented as Revolutionary War soldiers from Lovettsville and who were also members of New Jerusalem Lutheran Church along with the Axline family.)

What I have not found – despite searches and inquiries to Axline family researchers – are the military service records cited by Gen. Henry Axline.

Posey’s Virginia Battalion was also designated at times as the 1st Va. Battalion, and Febiger’s Battalion. This battalion was recruited and formed in 1780 to provide reinforcements for Gen. Nathaniel Greene in the Southern theatre. Col. Christian Febiger was nominally in charge of recruiting for Greene, but he was deployed in Philadelphia for obtaining supplies (he was in charge of commissariat duties there – which often meant obtaining supplies from civilians). Thomas Posey, a colleague of Febiger’s, was sent to Virginia to recruit for Febiger. His recruiting post was at the Old Cumberland Court House (now Powhatan, Va.); another recruiting post was at Winchester, which is of course much closer to Loudoun County. In summer of 1781 Col. Posey’s Battalion was deployed in the Yorktown campaign; after Cornwallis’s surrender it was sent to South Carolina to reinforce Greene. Posey’s Battalion was in South Carolina by January 1782, and was engaged against Creek Indians and Georgia loyalists at Sharon, near Savanna, Georgia, on June 23, 1782. Sporadic skirmishing along the frontier continued through the summer, and by October 1782, Posey’s Battalion was on the march home. It was disbanded in early 1783.

Where WAS John Axline?

So, if we are looking at the same John Axline/Exline – and it seems we are — he was in military service in South Carolina and Georgia during 1782, when we have muster rolls listing him in service from April to September 1782. He would hardly have been in a position to go home and make gunpowder from there.

On the other hand, we have pretty good evidence – from his wife’s diary – that John was engaged in making gunpowder, in an area subject to raids by British troops. This seems most likely to have been in Chester County, Pa., a center of gunpowder manufacture and the location of this father’s home. And this seems likely to have been prior to June 1778, when British troops withdrew from Philadelphia.

More important: there were no British troops in the Virginia Piedmont or Loudoun County at any time during the War, except for prisoners. British troops didn’t go wandering around the interior or frontier areas confiscating property unless they were garrisoned nearby. I don’t see how it could have been possible for British troops to have confiscated John’s property in Loudoun County or anywhere in this area.

But if John had gone back to Pennsylvania early in the war, he could well have been engaged in gunpowder production, and this would explain his wife’s diary entry. And his military service records prove military service in the Southern theatre at the end of the war. So he may well have have been engaged in gunpowder production, and have also served in the Virginia Line – just probably not at the same time.

We still hope to someday find the military records which Gen. Henry A. Axline examined in the late 19th century – and these would likely shed further light on the fascinating story of our local Revolutionary soldier and patriot, John Axline.