By: Eirik Frederick Harteis

Introduction:

On July 9, the Lovettsville Historical Society held a symposium on the topic of “Slavery in the German Settlement,” which featured a presentation by Eirik Harteis, a history teacher from Taylorstown and a member of the Lovettsville Historical Society’s Advisory Board. Harteis has been studying the history of the neighboring 1810 Stoutsenberger Farm for many years, trying to understand why a Revolutionary War veteran living in the German Settlement would own ten slaves by the time he died in 1837. Traditionally, it was believed that the ethnic Germans in northern Loudoun County were opposed to slavery and owned few if any enslaved persons.

The following article embodies the research on which Harteis’s presentation was based; much of which was presented in his talk on July 9. Following his presentation, we heard discussion from a panel of local historians: (from left to right in the featured picture above) Dennis Frye, Wynne Saffer, Bronwen Souders, Donna Bohannon, Lori Kimball, and John Souders, with Rich Gillespie as moderator (Photo: John Kimball). The discussion, which also included the audience, probed many of the nuances of the local slavery situation, including the evolution and “Americanization” of the German Settlement from its pre-Revolutionary War founding, up to the Civil War, with its increase of slaveholding over that time period. Areas in which further research is needed were also raised. The discussion was serious and thought-provoking and will be continuing over the coming months and years.

We are grateful to Eirik for his ground-breaking research which has kicked off this long-needed discussion of our actual history.

Good history supports good civic conversations. With the U.S. Supreme Court striking down affirmative action in higher education, Florida history education standards making national news, and a report on reparations now under consideration by the California legislature, the history of slavery in the United States is the subject of increasing debate. It has long been established that in the mid-nineteenth century, slavery threw a large shadow over Loudoun County too.

Loudoun’s population in 1860 was approximately 22,000 people. More than five thousand of these men, women, and children were enslaved. Another 1,200 free black people comprised a racial undercaste. These numbers were a growing source of concern for many white Loudouners. In the early 1830s, the sale and forced migrations of many enslaved Loudouners to the deep South began to rise to historic highs. In numerous cases, this led to the brutal breakup of families. Resistance in the form of Nat Turner’s rebellion of 1831 resulted in the death of more than 50 whites and between 100 and 200 blacks in southeastern Virginia and sent shockwaves throughout the Commonwealth.

In response, Virginia passed a law forbidding African Americans to assemble, preach, or learn to read or write. In 1836, the County Attorney petitioned the state legislature to expel 36 free blacks from Loudoun to Africa. In 1840, the free black man Leonard Grimes was convicted of helping an enslaved mother and her daughter gain freedom. In 1846, free man Nelson Talbor Gant was tried and acquitted for stealing his enslaved wife. In the face of rising Black resistance to slavery, William Smith, the president of Randolph Macon College, delivered an address from the Leesburg courthouse in defense of slavery in 1849, asserting that it was “right in itself and sanctioned by the Bible.”[1] Not all white Loudouners agreed.

Loudoun’s white population comprised a patchwork of religious, racial, and cultural entities. Rooted in eastern and southern Loudoun was the planter class. Often descended from Tidewater settlers, these Anglican planters developed large plantations utilizing traditional agriculture and enslaved labor. To the west of the Catoctin Ridge and around the area of the village of Waterford was Quaker country. Nearly a quarter of the farmers who lived in this area were members of the Society of Friends. Distinct in terms of dress, speech, and religious practice, they generally employed many of the new approaches to agriculture and opposed slavery. By 1830, Waterford had become Loudoun’s largest town and as many as one in five residents were free African Americans.[2] North of Quaker country was the German Settlement. Centered around Lovettsville, the farms in this region were also generally small, families were large, and the homes were often humble log dwellings.[3]

This divided geography caught people’s attention. In 1835 an entry in Martin’s Gazetteer noted that “a very considerable contrast is observable in the manners of the inhabitants in different sections of the county. That part of it lying [northwest] of Waterford was originally settled principally by Germans, and is now called the German settlement… In [this section] the farms are generally from one to three hundred acres each and are mostly cultivated by free labor. In the [south] and [east] parts of the county the farms are many of them much larger and principally cultivated by slave labor.”[4]While their use of enslaved labor and farm size differed, farmers largely grew the same crops: wheat, rye, corn, and oats.[5]

These separate communities also stood out for mapmaker Yardley Taylor. Writing in 1853, he observed “The north-western parts of the county were originally settled by Germans, principally from Pennsylvania, and many of their descendants still remain. Here the farms are generally small, and well cultivated, and land rates high…The central portion of the county was originally settled by emigrants from Pennsylvania, and the then neighbouring colonies, among whom were many members of the Society of Friends. Here the farms are of moderate size, and chiefly cultivated by free labour…[i]n the southern parts of the county, the farms are larger and generally cultivated by slave labour.”[6] Briscoe Goodhart, a native of Taylorstown echoed this geography in an article for a local newspaper published in 1900. “The Germans of [northern] Loudoun were opposed to slavery which they evidenced both by precept and example. Probably not more than one dozen slaves were ever owned by the Germans of Loudoun.”[7]

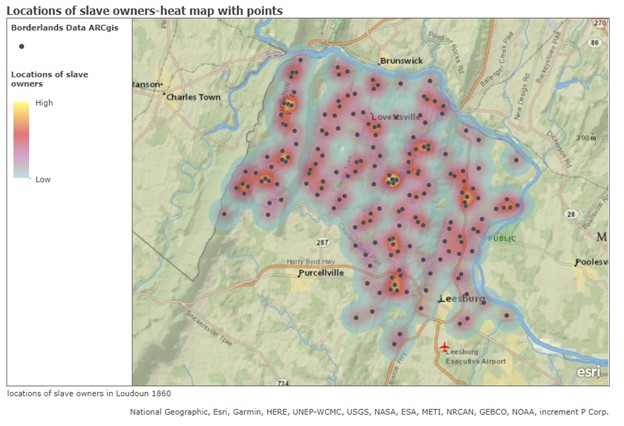

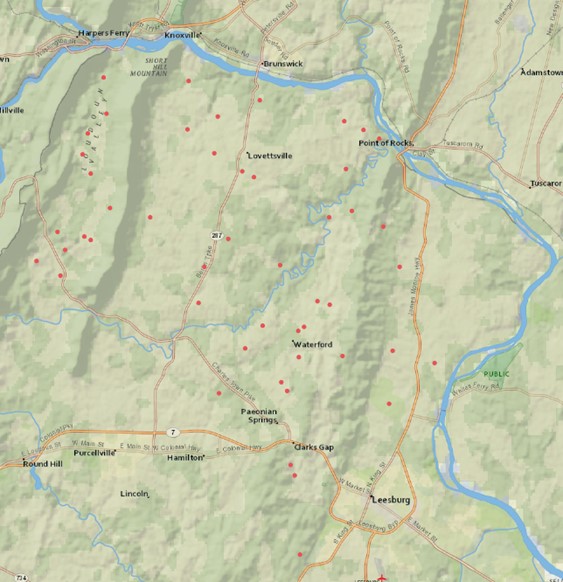

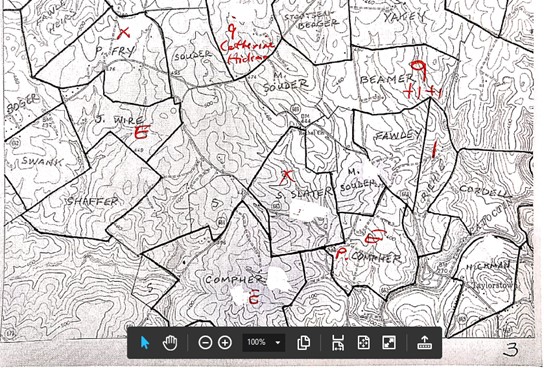

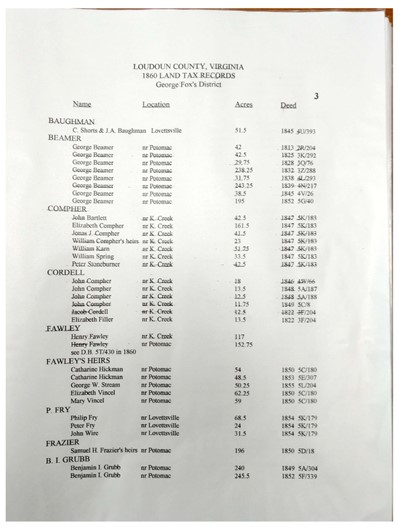

Was the geography of enslavement in Loudoun as distinctive as these reports suggest? Was the landscape marked with the noticeable belts of high levels of enslaved people that contrasted with bubbles with low levels of enslavement as these sources suggest? One way to explore this question is to map the data related to slavery at the time. The methodology employed by this study started with land records found in Loudoun County, Virginia 1860 Land Tax Map, a resource compiled by historian Wynne Saffer. This source charts the property boundary lines with the names of property owners in 1860 Loudoun. (See Appendix A.) The Loudoun County, Virginia 1860 Land Tax Map also includes charts with the names of property owners, information on location, number of acres, and location of the deed used to compile the information. (See Appendix B.)

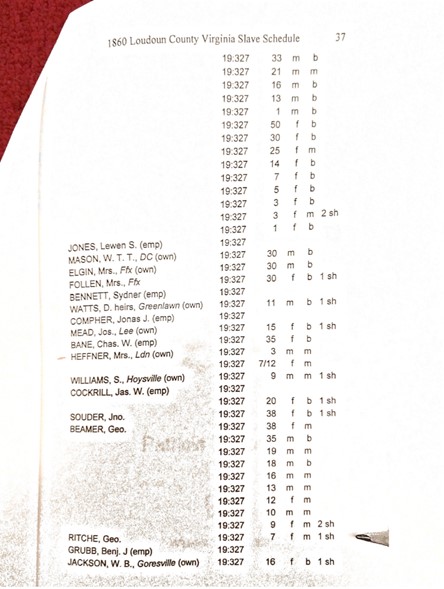

The location information in this source was matched with listings of enslavers and enslaved people found in the 1860 Slave Schedule for Loudoun County as compiled by Patricia Duncan. This book compiles and edits U.S. Census data with the following details:

- the name of slaveholders or employer (renter) and location if stated

- the age and gender of enslaved people

- the gender and color (black or mulatto)

- the number of slave houses.[8]

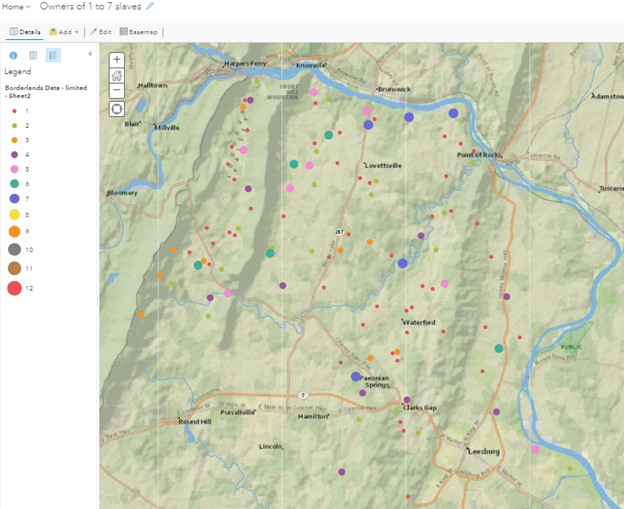

Data from these two sources were entered into a spreadsheet and uploaded to ArcGIS software producing a series of maps of northern Loudoun illustrating the geography of enslavement.

Did the pattern of slave-owning in northern Loudoun County in 1860 reflect the views of the primary sources? Was there little enslavement around Lovettsville and Waterford? The maps suggest that in 1860 there were no significant areas in northern Loudoun County devoid of the presence of slavery. On a macro level, enslavement seems to be spread equally throughout the northern part of Loudoun. Except for towns and mountain ridges (which were excluded from the study because they were not included in the Tax Map source due to the density), map 1 shows slave ownership spread throughout northern Loudoun. The data does not suggest a discernable presence of a religious, cultural, economic, or ideological objection to the institution of slavery in a way that is demonstrated in its geographic distribution. There are no recognizable belts of high levels of enslavement, or bubbles of low levels, when it came to slave ownership in 1860.

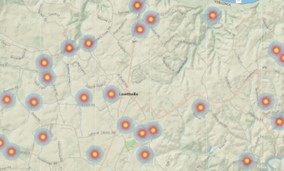

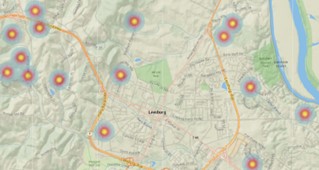

At a micro level, the area around the town of Lovettsville (the geographic center of the German-American community) was roughly equal to the area around Leesburg (the county seat and center for the planter class) in terms of the number of owners of slaves as illustrated by Maps 2 and 3.

If one were traveling to the Potomac River along the Berlin Turnpike (Route 287 today) from the Charles Town Pike in 1860, records indicate that one would pass 10 properties with enslaved people along the nine-mile journey. On a journey of a similar length from north of Leesburg to the Potomac along today’s James Monroe Highway, one would pass 11 properties with enslaved people.

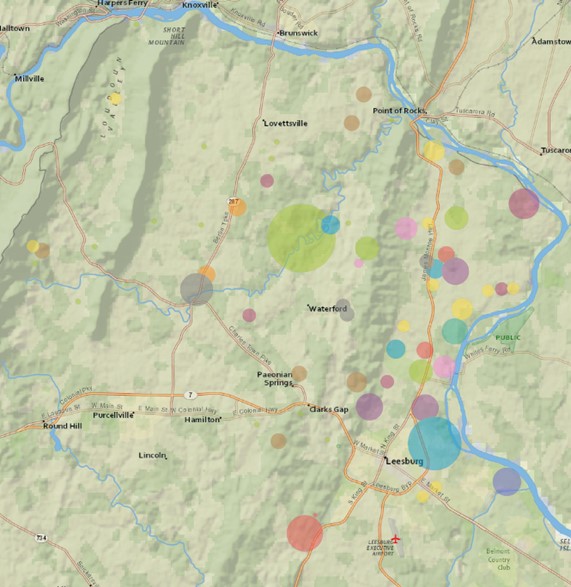

However, when factoring in the number of people enslaved at a property, a different pattern emerges. Of the 48 enslavers who were counted with just one captive, all but five were located west of the Catoctin Mountain ridge. A high concentration was found between Short Hill Mountain and the Blue Ridge. Few were located east of the Catoctin Mountains around Leesburg or near today’s James Monroe Highway.

A similar pattern appears when mapping owners of two, three, four, five, six, and seven captives.

It is not until the owners of eight captives or more were identified that we see a change in this pattern. This is due to the fact that as the number of enslaved people per owner climbs higher, it is difficult to get a meaningful geographic distribution of owners due to their limited owners. There are only three slave owners counted with 10 captives in northern Loudoun in 1860. However, if all the owners of 8 or more captives are charted into one map, for the first time a significant majority are found on the east side of the Catoctin Mountains.

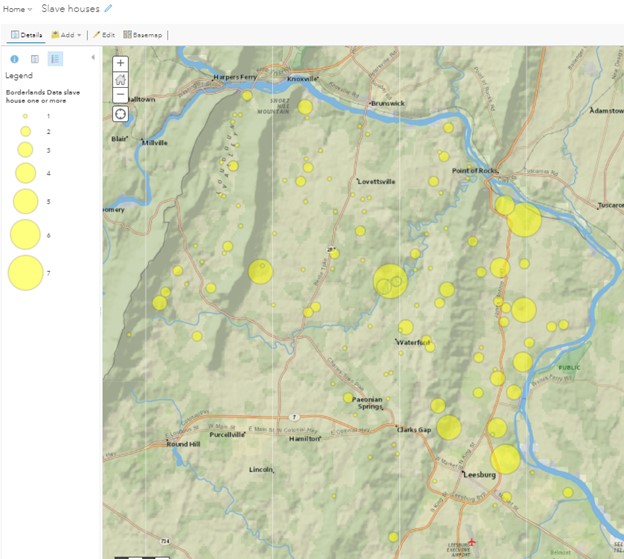

When data from the location and number of slave houses on a property is overlaid on northern Loudoun County, we find a similar pattern. Houses for slaves are spread in an equally random array across the area. However, while there are ten properties with four to seven slave houses, eight are found east of the Catoctin Mountain range. Most properties with just one slave house, 61 in total, are found west of the mountains.

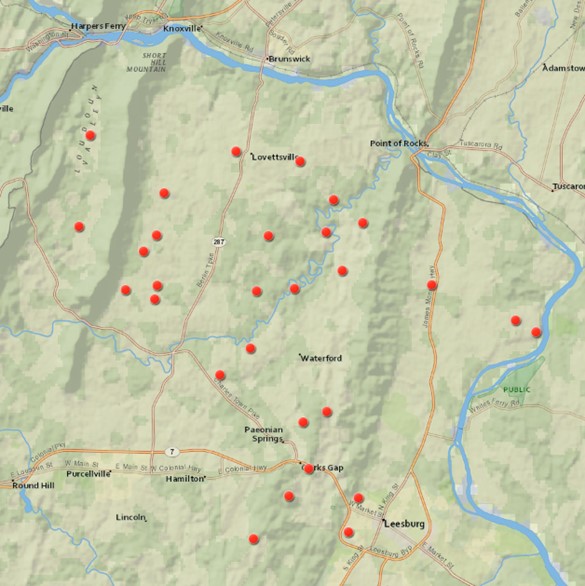

An analysis of those who rented enslaved people in 1860 reflects this trend. In the Virginia Piedmont during the late antebellum period, it was not uncommon for both slave-owning and non-slave-owning whites to rent slaves for a year. When the census count was taken, it identified the people who were renting, labeling them as “employers.” It did not count the number rented by an enslaver. Yet when this data is mapped, the rental of enslaved laborers was not equally distributed. There were 28 total people counted as renting slaves in the Fox tax district, which covered the northern third of Loudoun County. All but seven renters were located west of the Catoctin Mountains. It can be safely assumed that most of the rentals involved small numbers of enslaved laborers. When considering the location of properties with rented slaves and those properties with less than eight enslaved people, the two seem to share the same geography. Enslavers with fewer slaves were more likely to rent.

Taken together, what do these maps suggest? While the presence of slavery was equally distributed throughout northern Loudoun, enslavers of small numbers of slaves were concentrated in the western section of the tax district. Owners of large numbers of slaves were in the eastern parts of the district. The two are separated by the low-slung ridge of the Catoctin Mountains. The rental of slaves is more prominent on the western side. Properties with slave houses are most densely clustered and include larger numbers on the eastern side of the tax district.

In northern Loudoun, 47 people claimed one enslaved African American. Just three claimed more than 30. Thomas Clagett’s 32 captives and Horatio Trundell’s 41 captives were located on land in the Leesburg area, east of the Catoctin Mountains. These plantations were just north of Elizabeth Carter’s Oatlands plantation, the site of Loudoun’s largest enslaver in 1860 with a count of 128. As such, they probably fit in well among their neighbors. Sanford J. Ramey’s 62 captives were located on the west side of the mountains. In 1860, he had the second-largest enslaved population in all of Loudoun County. Sandwiched between Quaker Waterford and the German Settlement, Ramey’s plantation of 300 acres and his property in humans must have stood out among his neighbors.

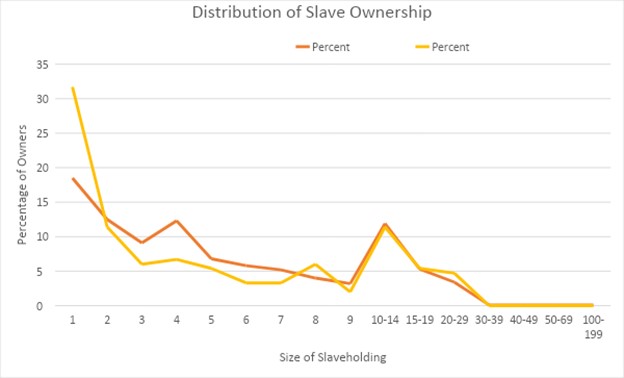

The level of enslavement in northern Loudoun reflected similar trends in the rest of the county. A chart of 180 slaveholders in the north is comparable to the 670 slaveholders counted in all of Loudoun County. Except for those who enslaved just one person (the north was 31.7% to Loudoun County’s 18.5%), the percentages for levels of slave ownership between the regions are close. Enslavers of five, seven, and eight are just two percentage points different. Both groups are nearly identical regarding slave ownership of 10 to 19 captives.

Slavery in Loudoun, like in many places in 19th-century America, was not a monolithic institution. While there may have been periods when enslavement was concentrated in some places and limited in others, by 1860 the data suggest something different. Enslavement was present throughout much of Loudoun. However, the data indicates there were real differences in the number and nature of enslavement in northern Loudoun. East of the Catoctin Ridge we find larger numbers of bondspeople and larger numbers of slave houses. West of the Catoctin mountains we find more rentals of the enslaved people and smaller numbers per property. Perhaps these differences illustrate the presence of two different societies. To the east, we have a slave society. In the west, we have a society with slaves.

Appendix A – 1860 Land Tax Map with number of enslaved people per property

This map shows the number of enslaved people listed in the Slave Schedule on the most likely property.

Appendix B – Data Used to Compile 1860 Land Tax Map

This document shows the information used to compile the land tax map. It includes the name found on the map, the owner or owners, location, acres, date, and location of the deed.

Appendix C – 1860 Slave Schedule for Loudoun County with individual information.

This book contains information about enslavers and enslaved. The left column lists the name of the owner or employer (renter) with location in some listings. The next column lists the location in the census. The next two columns contain the age and gender of the enslaved. This is followed by a listing of “black” or “mulatto.” The last column identifies the number of slave houses on the property.

[1] Charles Poland, From Frontier to Suburbia (1976), 142.

[2] Eugene M. Scheel, Loudoun Discovered: Communities, Corners & Crossroads (Leesburg, VA: Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, 2002), 18.

[3] Scheel, Loudoun Discovered, Vol. 5, 63., Poland, From Frontier, 40-43.

[4] William Henry Brockenbrough and Joseph Meredith Toner Collection. A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer of Virginia, and the District of Columbia. edited by Martin, Joseph, Of Charlottesville, Va Charlottesville: J. Martin, 1835. Web. https://lccn.loc.gov/rc01002834. 212.

[5] Martin, Joseph, Of Charlottesville, VA, editor. A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer of Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Charlottesville, J. Martin, 1835. Web. https://lccn.loc.gov/rc01002834, [Page 211].

[6] Yardley Taylor, “Memoir of Loudoun County, Virginia” (1853), accessed at Internet Archive. 7.

[7] Briscoe Goodhart, The German Settlement (Hamilton, VA: Loudoun Telephone Office, 1900), 18.

[8] See Appendix C for details.

[9] Poland, From Frontier, 133.