By Edward Spannaus

Up through the time of the American Revolution, Lovettsville’s two churches were in a legal limbo. There was but one Established Church in the Virginia colony: that was the Church of England, or the Anglican Church – and only Anglican ministers, or priests, were permitted to conduct marriages and administer other church sacraments. Everyone was taxed for support of the Established Church.

But then, on January 16, 1786, Virginia’s Religious Freedom Law (“An Act for Establishing Religious Freedom”) was enacted by the General Assembly and was signed into law on January 19.

A little more than two months later, on March 25, 1786, the local Lutheran congregation (now New Jerusalem) adopted its first constitution, declaring itself a “church.”

And two years later, in 1788, the local adherents of the German Reformed faith (now St. James) organized themselves into a church body and began keeping their own “church book” the next year.

Were all these actions connected? Let’s look at the background.

Church History: The German Reformed[1]

First, we glance back to the early history of Lovettsville’s two “legacy” churches and summarize some of what we know about them.[2]

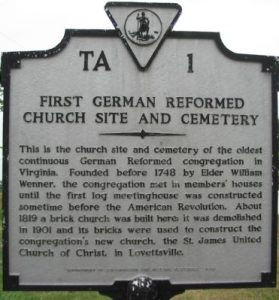

In his history of “the Lovettsville Reformed Charge” published in 1901, the then-pastor Rev. L. T. Lampe wrote[3] that the first few German emigrants arrived in Upper Loudoun in 1727, but that the first organized influx of German settlers from Pennsylvania came here in 1734. “Our Reformed congregation, with her sister, the Lutheran, was organized about the first year of the incoming,” Rev. Lampe wrote, cautioning that “no records exist to verify this assertion.” The early members of both faiths met in homes for many decades, with the first church or school buildings estimated to have been erected no earlier than 1765 (Lutheran), or 1775 (Reformed).

When the pioneer missionary of the German Reformed Church, Rev. Michael Schlatter, visited the German Settlement in 1748, he stayed at the home of Elder Wenner, whom he called “a pious elder of the Reformed congregation, living near the Potomac River opposite Berlin.”

In August 1767, the Rev. Charles Lange, from the Frederick Reformed congregation, visited “the destitute churches” in Virginia. He confirmed 13 persons, and administered communion to 35 more persons, in Loudoun.

Rev. Frederick Henop, who succeeded Lange, arrived in Frederick in 1769-70, and preached once a month at the “Short Hill” congregation–as it came to be known.

Henop was succeeded by the Rev. J. W. Runkel, who came to Frederick in 1784. He is reported to have extended his field of labor to the Short Hill in March 1785, adding it to his charge.

Rev. Henry Giese (a somewhat controversial figure[4]) came to Frederick in 1782, from which he visited the Short Hill and other congregation; a few years later, he moved to Loudoun County and became the first resident pastor in the German Settlement. In 1788 the Short Hill congregation organized itself into a formal congregation, and Giese began keeping a separate church book (register) in September 1789. In the first pages of the church register, he lists a number of earlier baptisms (it is unclear who performed them or when), and also number of baptisms performed by himself in December 1789, for children born in 1786 and 1787. (This raises the question, of whether it was felt that 1786 was the first time that he or others could legally perform a baptism.) Giese also lists communicants for August 1789, including 40 adults, plus 14 children for whom this was their first communion.

Church History: The German Lutherans

The earliest known reference to Lutherans living in this area, is a report published in Hanover (Germany) in 1737, in which the early Lutheran missionary, Rev. John Caspar Stoever Sr., states that he visited the congregation in the German settlement in what is now Loudoun County, in 1733-1734.[5] Stoever was the pastor of Hebron Lutheran Church in Madison County, VA (the community of German iron workers known as “Germanna.”) Stoever was travelling from Hebron back to the German states to seek financial and other assistance for these first Virginia Lutherans.

Little is known about the Lutherans in Loudoun County until 1765, the date usually given for the organization of the congregation known in those days as “the Evangelical Lutheran Church at the Short Hill.” This was a preaching point of Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick, Maryland. Any records of pastoral acts – baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burials – were kept in the church book at Frederick. The pastor in Frederick at that time (1762-1768) was the Rev. Johann Samuel Schwerdtfeger, who is regarded as New Jerusalem’s first pastor.

Schwerdtfeger was succeeded by the Rev. John Andrew Krug in 1771; Krug served the Short Hill congregation for 25 years as part of the Frederick charge. Krug’s entries in the Frederick church register are more detailed and begin to show locations. Thus, the first marriage in the Frederick church register identifying Loudoun County as the location was in April 1772, and the Frederick records show 30 boys and girls (of ages 14-22) being confirmed in Loudoun County in May 1772.

In 1784, under Pastor Krug, a separate church register is begun for the Lutheran Church in Loudoun County, so that pastoral acts for the Loudoun Lutherans are no longer recorded in Frederick unless they actually took place there. But the Lutheran Church here is still part of the “Frederick Charge,” and it does not get a full-time, resident pastor until 1832.

On March 25, 1786, the Lutherans in Loudoun County adopted their first church constitution. Its opening section reads (as translated from the original German):

“The Elders and Deacons of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Schart Hill community in said county today have determined and voted on the following articles which they think may best serve the church….”

Thus, the Lutherans in The German Settlement came to regard themselves as a distinct church congregation from the “mother church” in Frederick, while still remaining affiliated with the Ministerium of Pennsylvania which included Maryland. It seems that they now regarded themselves as a separate entity, legally operating within the Commonwealth of Virginia.

So, it appears evident, that within a short time after the adoption of Virginia’s Religious Freedom Act, both churches in the German Settlement had organized themselves as separate church bodies, distinct from their parent churches in Maryland–although still affiliated with them.

The evolution of religious freedom in Virginia

How was it, that those of the Lutheran and Reformed faith in the German Settlement were apparently permitted to practice their religion unmolested, while Baptists and some others were being persecuted in Virginia, and even in Loudoun County?

The laws respecting the Established Church in Virginia were enforced with greater or lesser vigor, depending on the geographical location and the time period. Enforcement was strictest against the “dissenting” churches in those areas where the Anglican Church was the strongest, and also in the period just prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. For example, in Botetourt County, a Baptist minister was thrown in prison for celebrating the rite of marriage. In other areas east of the Blue Ridge, Baptists were also imprisoned, beaten, and sometimes dunked nearly to the point of death.[6]

Those singled out for the worst treatment were the Baptists, Presbyterians and sometimes the Quakers. Mennonites were sometimes regarded as dissenters against their established churches.[7]

The Lutherans and Reformed (Calvinists) were in a somewhat different category, since they represented the Established Churches in other parts of Europe. Since they grew out of a revolt two centuries earlier against the Roman Catholic Church, they were not considered as dissenters against the Church of England.

In fact, in some of the colonies, the Reformed (Dutch, German, or Swiss) were regarded as peers or partners of the Anglican Church, as were the German and Swedish Lutherans.

There were also expedient motives for toleration of the German churches – and even of the dissenting churches such as the Presbyterians – in the Shenandoah Valley. It was official policy of the Virginia colonial government to encourage settlement in the Valley as a line of defense against Indian attack. The settlement was largely made up of internal migration from Pennsylvania. In exchange for their availability to defend the frontier, the colonial authorities allowed the free exercise of religion. As Lutheran historian William E. Eisenberg put it: “Thus it was by tacit consent of colonial authorities that religious freedom became the unwritten law of the frontier.”[8]

This policy most likely had a spill-over effect into northern Loudoun County.

Colonial authorities on occasion encouraged Lutheran clergymen to go to London to get ordained in the Church of England. The first instance of this involved the Hebron Lutheran Church in the Piedmont’s Madison County, this being the first Lutheran church anywhere in Virginia. The Lutheran – and probably Reformed – pastors there were not allowed to perform marriages or baptisms, although they were exempted from paying tithes for upkeep of the Anglican Church.

The case of Peter Muhlenberg

The story of the Rev. Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg (later a General in the Continental Army) is instructive. The simplified version is that, in order to serve as a Lutheran minister in Virginia, he was compelled to travel to London to be ordained as an Anglican.

The reality is more complicated. With all the migration of Germans and Scotch-Irish from Pennsylvania, Anglicans were a distinct minority in the Shenandoah Valley – so much so that they had difficult filling their pulpits, or even seats on the Vestry. Lutherans were predominant in Beckford Parish in Dunmore (now Shenandoah) County. They had a congregation, but no pastor. The Anglicans didn’t even have a congregation there, much less a pastor. Through James Wood, Jr., of Winchester, the Anglicans approached the Rev. Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, the founder of the Lutheran Ministerium of Pennsylvania, for a minister who could speak both English and German, and who would be willing to travel to “Mother” (the Church of England in London) and become ordained as an Anglican. Papa Muhlenberg saw this as a solution for his restless and somewhat rebellious son, who had dropped out of school at Halle, Germany, and had joined a British regiment on its way to North America.

So Peter Muhlenberg was called by the Anglicans and ordained in the Church of England. He served six widespread Lutheran congregations in the Valley, and the two Anglican chapels in the parish. He could legally perform marriages and baptisms in Virginia. The arrangement worked quite well until the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, when Peter Muhlenberg famously threw off his clerical robes to reveal his officer’s uniform underneath. He recruited hundreds of Germans and others to join the militia and the Continental Army, and never returned to the ministry.[9]

Impact of the Revolution

Muhlenberg’s dual call was an elegant solution, but not one easily applied to other frontier churches. As the Revolution developed, Virginia authorities needed the support of the dissenters (especially Presbyterians and Baptists), and also of the German population, so they backed off of enforcement of the laws regarding religion. And of course, those who fought for independence from the British weren’t about to go back to subordinating themselves to the British religious authorities.

Opposition to the privileged status of the Anglican Church grew rapidly during the Revolution. Jefferson’s Religious Freedom Act was introduced into the General Assembly in 1779, and finally was passed in 1786.

The operative section of that statute states:

Be it enacted by General Assembly that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of Religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge or affect their civil capacities….

So, as to the question of whether our original Lovettsville churches were legal before 1786, the answer is “probably not.”

But, as we have seen, once our churches were fully legal, they lost little time in taking advantage of their new status.

[1] In some early Loudoun County legal documents, the Reformed Church in the German Settlement was called the “Calvinist” church.

[2] My thanks to the Evangelical Reformed United Church of Christ in Frederick for use of their library for research on the Lovettsville church.

[3] “Church History: Interesting Sketch of the Lovettsville Reformed Charge by the Pastor, Rev. L.T. Lampe,”

Brunswick Herald, June 14, 1910.

[4] Although some accuse him of hiding this fact, Heinrich Giese was a German auxiliary (“Hessian”) soldier and deserter, as were a number of others in his congregation.

[5] Stoever’s report is cited in a number of reputable sources, but I have been unable to find this statement.

[6] Lewis Peyton Little, Imprisoned preachers and religious liberty in Virginia, a narrative drawn largely from the official records of Virginia counties, unpublished manuscripts, letters, and other original sources (Lynchburg, Va., J.P. Bell Co., Inc., 1938).

[7] This point is made by Stephen L. Longenecker in his Shenandoah Religion: Outsiders and the Mainstream, 1716-1865 (Waco, Tex.: Baylor University Press, 2002).

[8] William E. Eisenberg, The Lutheran Church in Virginia 1717-1962 (Roanoke VA: Trustees of the Virginia Synod, Lutheran Church in America, 1967), p. 19.

[9] The story of Peter Muhlenberg is well, if incompletely, known. Two sources for the full story of his call as an Anglican, are Eisenberg, p. 58f, and Klaus Wust, The Virginia Germans (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1969, p. 74f.