The 241st anniversary of General Anthony Wayne’s crossing of the Potomac with his Pennsylvania troops was commemorated on June 4 at the “Spirit of Loudoun” Revolutionary War Memorial. The event at the Loudoun County Courthouse was sponsored by the Fairfax and Loudoun chapters of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), who were joined by other SAR chapters from Virginia and Maryland, as well as the Daughters and the Children of the American Revolution. Mayor Kelly Burke presented a proclamation from the Leesburg Town Council declaring June 4 as “Wayne’s Crossing Day.”

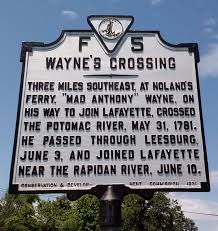

On May 31, 1781, Anthony Wayne and his troops crossed the river at Noland’s Ferry, and on June 3, they marched through Leesburg on their way to meet up with Lafayette in the central Piedmont. The linkage of Wayne’s Infantry, and Lafayette’s Light Infantry, to halt Cornwallis’s depredations in Virginia, commenced the campaign that led directly to the siege of Yorktown and the American victory in the war.

▲ On this site ▲

General Anthony Wayne

in the Spring of 1781,

established headquarters of

The Pennsylvania Line

and recruited for the campaign

which ended in the surrender of

Lord Cornwallis

October 19, 1781.

This tablet is erected in commemoration thereof by

▲ Yorktown Chapter ▲

Daughters of the American Revolution

The significance of Wayne’s Crossing into Virginia was discussed in a presentation by Jeff Thomas, Past President of the Virginia Society of the SAR. He began by quoting from a May 17, 1781 message to Wayne from the Board of War, urging him to begin his march immediately, and warning of serious consequences if more troops did not reinforce Lafayette in Virginia. On May 26, Wayne and his troops left York, Pennsylvania. After five days, they reached the Potomac and crossed at Noland’s Ferry, which was serving as an armaments depot for Loudoun County. They crossed there, rather than further downstream towards Georgetown, because of warnings that Cornwallis could be headed to Alexandria.

There had been a couple of other mass crossings at Noland’s Ferry. The first was of Hessian prisoners captured at Trenton; the largest was of 4300 British prisoners who had surrendered at Saratoga and were being marched to the Albemarle Barracks at Charlottesville.

When Wayne and his troops reached the Potomac, the river was swollen and turbulent due to heavy rains, and crossing was perilous. One small boat overturned, and cannon and ammunition were lost, as well as several men.

On June 3, Wayne’s troops reached Leesburg, which was the only major town along the Carolina Road. Leesburg had less than 500 residents, but they had strong patriotic leanings, Thomas said. From Leesburg, Wayne marched along the Carolina Road, headed toward Fredericksburg.

On June 10, Wayne and his troops met up with Lafayette at the Rapidan River, after having marched 200 miles in just over two weeks.

As Thomas described it, Virginia was in distress when Lafayette arrived there in March with 1200 troops to help defend against British incursions. In January, Benedict Arnold (now working for the British), had captured Richmond with his 1600 troops and burned the city to the ground. 2000 more British troops under Gen. William Phillips had arrived in April and moved toward Williamsburg and Petersburg. Lafayette stopped Phillips’s advance at Richmond. But in mid-May, Cornwallis entered Virginia from North Carolina with 7000 well-trained, battle-tested regulars, and he set out in pursuit of Lafayette.

On June 3, as General Wayne’s troops were marching through Leesburg, Cornwallis attempted, but failed, to capture Governor Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia Legislature at Charlottesville.

With only 3000 men, Lafayette’s force was no match for Cornwallis, and so he returned to Fredericksburg to wait for Anthony Wayne. After Wayne’s arrival, Cornwallis headed for the coast, with Lafayette and Wayne in pursuit at a distance, in what some have called a game of “cat and mouse.”

When Cornwallis decided to cross the James River, Lafayette seized what he saw as an opening to attack the British rear guard, in what became known as the Battle of Greenspring. After an extended skirmish, with the British suffering significant losses from Wayne’s Infantry and his riflemen, Cornwallis appeared to retreat. But in fact, his forces had not crossed the James, but were lying in wait in the woods, on Wayne’s right and left flanks.

Lafayette saw what was happening, but it was too late to warn Wayne. Wayne, in one of the war’s most audacious moves, ordered an attack. He directed his artillery to fire, and his men to fix bayonets and charge the overwhelming British forces. This was not what the British expected. Wayne’s charge halted the British attack, allowed time for an orderly retreat, and, as Thomas said, it probably saved his troops from destruction.

The British Commander now gave up on his attempt to capture Lafayette, and he completed his withdrawal across the James and moved on to Portsmouth to resupply his forces. In August Cornwallis took up a position on the York River, setting the stage for the siege of Yorktown after Washington’s and Rochambeau’s forces arrived, having traveled down the coast on foot and on ship.

As Jeff Thomas summed it up: “Wayne’s Potomac Crossing and reinforcement of Lafayette, truly turned the tide of the war in Virginia,” which ultimately resulted in the surrender of Cornwallis on October 19, 1781. “Wayne’s forces had truly been the tip of the spear leading to that outcome.”

HOW WAYNE GOT TO LOUDOUN COUNTY

After Jeff Thomas spoke at the Wayne’s Crossing event, a report on Wayne’s march through western Maryland was presented by Edward Spannaus, President of the Sgt. Lawrence Everhart Chapter of the SAR in Frederick County, Maryland. Following these remarks, Spannaus discussed plans by his chapter and the Westminster Chapter in Carroll County MD, to seek the emplacement of historic markers at the sites of Wayne’s encampments in those two counties. He suggested that the Virginia chapters may want to do the same, marking Wayne’s march to where he met Lafayette, and perhaps then the road to Yorktown.

Following is the text from which Spannaus spoke.

On 26 May 1781, General Anthony Wayne wrote to George Washington from York, Pennsylvania, enclosing a return of the detachment of infantry under his command. He also reported on two Courts Martial, saying that:

“harmony and discipline again pervades the lines, the troops have this morning commenced their march after being retarded four days by a succession of extreme wet weather.”

What did it take for Wayne to assemble this force of 900 to a 1000 officers and men?

The mutiny at York was the second that Wayne had faced that year. The Pennsylvania Line, which he commanded, had mutinied in January at Morristown – over the troops’ enlistments being up, and the deplorable conditions in which they lived, without pay. Wayne had complained to Washington and the Board of War about his knocking on doors and finding the treasuries empty. The settlement of the January mutiny allowed many men to leave the army, and five regiments were disbanded.

It fell to Wayne to reorganize the remaining men and regiments, and to launch a recruiting drive in Pennsylvania. And of course the new enlistees had to be trained and equipped, which took time.

All the while George Washington was pushing Wayne to get moving to Virginia to reinforce Lafayette, who was trying to fend off the British forces around Petersburg and Richmond with his much smaller force. And Lafayette was personally imploring Wayne, for whom he had great respect, to get to central Virginia as quickly as possible. As Cornwallis neared Petersburg and Richmond, Lafayette sent a plea to Wayne:

“Where this letter will meet you, I am not able to ascertain, But ardently wish it may be near this place where your presence is absolutely necessary.”

On May 7, Wayne had informed Washington of the difficulties caused by lack of payments, and that the rumors that his force might be needed closer to home rather than in Virginia, were slowing things down, but now, regiments were on the march toward York, coming from Harrisburg, Easton, and others from Carlisle.

Then Wayne was faced with another mutiny, which he was determined to put down with whatever force was necessary. After several days of Courts Martial of 20 mutineers, six were sentenced to death, two were pardoned, and the executions of the other four were carried out in front of the assembled troops on May 22. This may seem harsh, but without such firm measures, Wayne likely wouldn’t have had any troops to march to Virginia.

After four more days of horrendous weather, Wayne communicated to Washington on May 26 that he was ready to move out. His force consisted of about 950 men (78 officers, 880 rank & file).

Saturday, May 26: They left camp at York at 8:00 a.m. on Saturday – which was a late start, probably due to the weather. They marched 12 miles. The route they followed was then called the “Monocacy Road” (present-day MD Route 194). This was the primary route used by the Pennsylvania Germans who flooded into Maryland — and some of those then into northern Loudoun County, to what was then called “The German Settlement” (today’s Lovettsville).

Sunday, May 27: started at 5:00 a.m., marched through Hanover to Peter Little’s Town (Littletown), another 12 miles.

Monday, May 28: marched 4 miles to state line, entered Maryland, passed through Taneytown and camped at Bruce’s Mills on the Big Pipe Creek, total 16 miles.

Tuesday, May 29: continued on the Monocacy Road to the Monocacy River near Frederick (now Ceresville), ferried across the Monocacy and camped on the west/southwest side of the river. 14-15 miles. Like the Bruceville crossing and camp, this crossing today is in pretty much the same exact location as it was during the Revolutionary War.

Wed. May 30: they spent the day washing their clothes and cleaning their weapons, and were reviewed late afternoon by Gen. Wayne.

Thursday, May 31: left camp at 5:00 a.m., march four miles to Frederick Town, and marched down Market Street past the prison barracks (later known as the “Hessian Barracks,”) which now housed British officers captured at Saratoga. Some say that Wayne wanted to remind them that the defeat of Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga brought France into the war on the side of the American revolutionaries.

Marching down the Buckeystown Pike (the “Carolina Road”) from Frederick, they reached Noland’s Ferry on the Potomac around 3:00 p.m.

It had been six days of marching and stopping through Pennsylvania and Maryland, along the old colonial roads, and amidst scorching daytime temperatures and powerful thunderstorms at night. There would be more of the same in Virginia. But, as Jeff Thomas has just showed, Wayne’s march was a key building block for the victory at Yorktown four months later.