By Edward Spannaus

In Part II of this series, we learned that the Tankerville lands, as Loyalist properties, had been “sequestered” during the Revolutionary War, and saw how the Dowager of Tankerville had appealed to General George Washington in 1783 to help in freeing up the lands so that the Tankerville family could dispose of them. Gen. Washington declined to accept the Tankerville’s Power of Attorney, but referred the Tankerville matter, including the Dowager’s letter, to Edmund Randolph, then the Attorney General of Virginia.

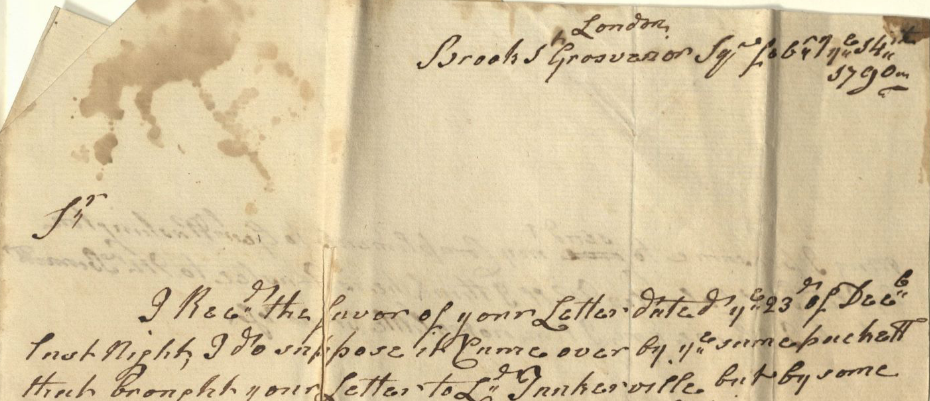

The Dowager Tankerville was not one to be put off. When nothing had happened to free up the family estate in the Virginia colony, she attempted to appeal to the United States Ambassador to Great Britain, John Adams – who happened to be a neighbor of hers on Grosvenor Square in London.

Lady Tankerville asked the American ex-patriot, sculptor, and sometimes spy, Patience Lovell Wright – a friends of the Adamses – if she would ask the Ambassador whether the U.S. Congress had repealed the law against the Tankerville Estate in Virginia and in “Lord Fairfax’s County.” She also asked Wright to inquire of Adams if he had heard that no trade agreements with America are to be settled until the laws regarding confiscation of Tory lands are repealed. She reported other intelligence about the King preventing any implementation of the Treaty of Paris until the Americans complied with the article of the Treaty regarding restoration of Loyalist Estates. Wright did send a note to John Adams, but there is no evidence that the Ambassador did anything about it. [i]

Why was the Dowager getting so impatient? Let’s pick up the story where we left it in the previous installment.

As he often did on personal legal matters, George Washington turned to his former aide-de-camp Edmund Randolph, now Virginia’s Attorney General.[ii] Randolph, who was familiar with the issue from the November 1783 letters from Lady and Lord Tankerville, responded in February 1784, that he will advise Tankerville’s land agent Robert Hooe if he can do it “here,” but it is impossible for him to be “active” (i.e. he couldn’t to do anything publicly).[iii]

The trail of correspondence then dried up for a couple of years, during the period in which the status of Loyalist estates was up in the air for a while after the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, which took place in early 1784. There was much opposition in Virginia to the restoration of Loyalist property, and it wasn’t until four years later, in 1788, that the Virginia legislature repealed the last piece of legislation pertaining to confiscation and repayment of British debts.

Randolph’s advice

Some light on Randolph’s thinking on the matter is shown by a December 1787 letter from Hooe to Charles Bennett, the Earl of Tankerville, which seems to be the first letter in four years.[iv] Hooe says that although George Washington had declined the Power of Attorney, now-Governor Randolph will work with the him (Hooe), and will be ready for any court action – but of course as Governor, “it was not to be expected he could take an active part.” Randolph had first told Hooe, that he had thought there was no danger of any more confiscation, because the Treaty of Paris, which prohibited further confiscations, was the law of the land. But a few days later, upon reconsideration, he thought there might still be an attack on the Tankerville Estate under the Common Law of England, which still applied in Virginia. So the Tankerville estate was not yet secure from confiscation.

Randolph’s behind-the-scenes advice was to change the title (ownership) of the property, or to dispose of it. Then Hooe, adding his own advice concerning the depreciation of Virginia’s currency, wrote: “As to selling Land, Negro’s or Stock of any kind, it cannot be done at this time, without great loss, there being the greatest Scarcity of Money ever known.”

In early May 1788, after Hooe had been in Richmond and had a further consultation with Randolph, he wrote to Tankerville again.[v] Hooe reported that Randolph was “still more confirmed in his opinion that sales of Your Lordship’s and Mr. [Henry] Bennett’s landed Estates had better be made without loss of time.” With Randolph being Governor of Virginia, Hooe said, “he declined giving me his sentiments in writing.”

Hooe’s letter included copies of proceedings against Tankerville in Fairfax and Loudoun Counties, which he says were quashed by the General Court in Richmond (no record of those cases in the General Court can be found today).

Who can they sell to?

Most importantly, Hooe advised Tankerville that the estates were again considered as the property of the Earl and his brother Henry Bennett – an indication that the sequestration of their property had been lifted. But, he went on to warn Tankerville that, as things stood at that moment, neither the Tankerville/Bennetts nor their heirs could inherit the estates, nor could they sell them to anyone who was not a citizen of the United States. However, Hooe emphasized, they did at that time have the legal right to transfer or dispose of the land by a Deed of Sale to any who are U.S. citizens. Hooe also recommended that Henry Bennett come over to Virginia to be present for any land sales—which he apparently never did.

Hooe also added an optimistic note, referring to the fact that the new federal Constitution was about to go into effect: “However it is the general and prevailing opinion that the new proposed new federal system will take place in July at farthest, and as it will be the means of restoring good Government and confidence, these lands will be in demand, and sell very high upon Potomack, as we are making rapid strides in opening both the upper and lower falls … so as to navigate as high as Fort Cumberland. In that event you will run no risk in making Sales on Credit, and thereby I am certain You will be most amazingly benefitted.”

Then Hooe added a warning of some intrigue apparently underway: “In the mean time I beg recommend to you to be upon your guard against some Persons in Loudoun County, who I am informed mean to make you offers thro’ friends of theirs in London.”

Hooe concluded by advising Tankerville that the previous Power of Attorney sent to him was “not competent” for the purpose of selling all of his Virginia lands – should Tankerville resolve upon that – and a new one would be required. This would remain a problem for some time.

A few weeks before Hooe’s May 1788 letter, the Dowager of Tankerville wrote another letter to Hooe,[vi] telling him that she had sent various documents pertaining to Thomas Colville’s Will and estate, and suggested that Hooe might want to look into the ₤700 that Thomas Colville had left as a legacy to her son Charles, the Earl.[vii] “My Son Lord Tankerville is still in agreement,” the Dowager assured Hooe.

Trouble on the horizon

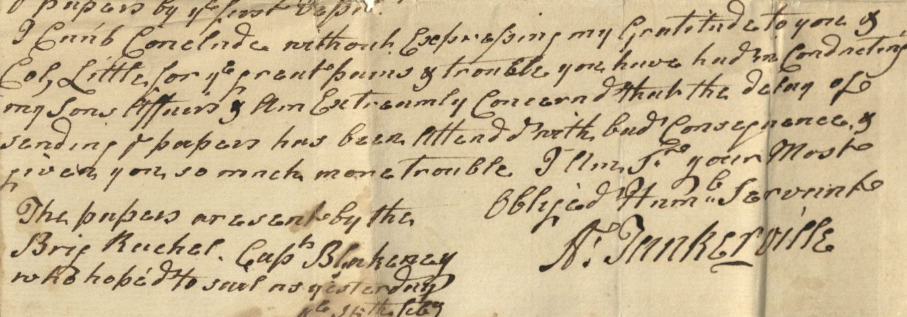

The next letter that survives was written by Hooe to Lord Tankerville at the end of 1789,[viii] but Hooe refers to a couple of letters earlier that year. This letter displays Hooe’s alarm that he has not yet received the documents he needs to defend against a growing number of lawsuits. Foremost among these missing papers is the Will of the 3rd Earl of Tankerville, who had died in 1767.

As opposed to the tone of his earlier letters, where he was confident that the courts would quash any challenge to the Tankerville estate, Hooe is now lamenting that he is having great difficulty in defending against lawsuits by tenants, and he complains that they are now being forced to grant leases to the tenants. And if they don’t get the needed documents soon, they may soon “see Mr. Bennett’s title to the whole Estate destroyed” for lack of his father’s Will.

In our next installment, we will look at some of the lawsuits filed by Tankerville’s tenants, and we will see what we can learn as to how Tankerville’s agents such as Hooe and Little treated, and abused, their tenants in the German Settlement.

[i] Massachusetts Historical Society, Papers of John Adams, Vol. 18, “From Patience Lovell Wright,” ante 19 Feb. 1786. An Editor’s Note indicates that is no evidence of Adams following up on Wright’s request.

[ii] Randolph’s father had returned to Britain at the outset of the American Revolution, but Edmund served as an aide-de-camp to Washington at the beginning of the Revolution. He was elected Virginia’s Attorney General, and also Mayor of Williamsburg in 1776, and also served as a delegate to the Continental Congress and later the 1787 Constitutional Convention. In 1786, he was elected Governor of Virginia. Washington appointed him the first Attorney General of the United States in 1789, and Secretary of State in 1794. Randolph was aligned with Jefferson in maintaining close relations with France during the French Revolution, and in trying to minimize Hamilton’s influence over George Washington. See Biography of Edmund Jennings Randolph, U.S. Department of State.

[iii] Edmund Randolph to George Washington, 19 February 1784, “Hooe, Hamilton, and Henderson Family Papers, 1756-1912” collection at the Wilson Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. collection at the Wilson Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. See Endnote 1 in previous article. The language and spelling have been modernized for readability.

[iv] Robert T. Hooe to Charles, Earl of Tankerville, 21 December 1787, “Hooe, Hamilton, and Henderson Family Papers, 1756-1912” cited above.

[v] Robert T. Hooe to Charles, Earl of Tankerville, 3 May 1788, “Hooe, Hamilton, and Henderson Family Papers, 1756-1912” cited above.

[vi] Lady Alicia Tankerville to Robert T. Hooe, 28 March 1789, “Hooe, Hamilton, and Henderson Family Papers, 1756-1912” cited above.

[vii] Thomas Colville was the brother of John Colville, from whom the 3rd Earl of Tankerville had acquired the 16,000-acre “Catoctin Tract.” When the 3rd Earl died in 1767, his sons Charles and Henry inherited the Catoctin Tract and other Virginia lands. George Washington was an Executor of Thomas Colville’s Will.

[viii] Robert T. Hooe to Charles, Earl of Tankerville, 23 December 1789, “Hooe, Hamilton, and Henderson Family Papers, 1756-1912” cited above.