By Edward Spannaus

Luther Slater is the only commissioned Union officer from the Civil War who is buried in Lovettsville. He was the highest-ranking elected officer in the Independent Loudoun Rangers, and but for his serious and disabling wounds, he almost certainly would have become its commanding officer over time. After the Civil War he served as Lovettsville postmaster for two years, and then accepted a position in the War Department in Washington, where he remained for over forty years, first in the medical corps, and then as a top official in the Records and Pension Office. Here is his story – an updated version of a lecture given to the Lovettsville Historical Society on August 14, 2011.

Luther Washington Slater was born in the area of Slater’s Crossroads – on what is now Slater Lane — near Lovettsville, on October 2, 1841. His great-great-grandfather Johannes Jacob Schloetzer (1709-1770), and his great-grandfather of the same name, emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1754 from the Rhineland Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz). The family next appears in the records of Augustus Lutheran Church in Trappe, Pennsylvania – the church congregation headed by the Rev. Henry Muhlenberg, regarded as the Patriarch of American Lutheranism.

Luther’s great-grandfather Jacob Slater (1729-1815) came to Loudoun County sometime between 1763 and 1766. In 1756 he had married Susanna Habicht, the widow of Casper Spring who was killed in the French-Indian War. (She had two sons from her first marriage, Andreas and Frederick Spring, who came with Jacob and Susanna to Loudoun County, and who are the founders of the Spring family in the Lovettsville area.) This Jacob Slater is recorded as having provided Patriotic Service during the American Revolution, by supplying beef to the Revolutionary Army.

Luther’s grandparents were John Slater (1763-1824) and Catherine Souder Slater (1772-1807), and his parents were Samuel Slater (1807-1898) and Barbary Myers (1808-1854), who were married in 1827. Samuel inherited his father’s farm. They had eight children, of whom Luther Washington was the seventh.

The Slaters were among the earliest members of New Jerusalem Lutheran Church near Lovettsville. Luther was baptized on May 6, 1842, and was confirmed in the Lutheran faith on May 28, 1854, and the records show him taking communion regularly during the periods he was at home. He probably attended the Tankerville School, which preceded the 1866 establishment of Bethel Lutheran Church at Tankerville by about two decades.

In 1859, young Luther Slater enrolled in the Preparatory Department of Roanoke College in Salem, Virginia, which was founded as the Virginia Institute in 1842, to prepare boys for enrolling in Pennsylvania (Gettysburg) College and the Gettysburg Lutheran Seminary.

During the following school year, 1860-61, Slater was enrolled in the Preparatory Department of Pennsylvania College at Gettysburg, until his studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War. He was a member of the Phrenakosmian Society, a literary organization. His course of study would suggest that he was preparing to enter the Lutheran Seminary at Gettysburg and to become a minister.

The Civil War decisively changed his course. From 1862 forward, Slater devoted his life to the service of his country – for the most part in the service of the United States Army and the War Department.

The Independent Loudoun Rangers

In June 1862, Samuel Means, a mill owner in Waterford, was commissioned as a Captain in the U.S. Army, and was authorized by the Secretary of War to recruit loyalists in northern Loudoun County to the Independent Loudoun Rangers, a cavalry and scouting unit in the service of the United States.ii Luther Slater and about two dozen others were mustered in on or about June 20, 1862, at either Lovettsville or Waterford; accounts differ.iii In early July, the Rangers encamped at the Reformed Church at Lovettsville — just outside of town, in what is now the German Reformed (St. James) cemetery. There, Capt. Means held elections for the other officers of the company; Slater was elected First Lieutenant, the number-two position in the unit.

At the beginning of August, the Rangers moved back to Waterford, where they learned the rudiments of military practice under the direction of their temporary drill-master, Charles Webster. After the arrival of their uniforms from Harpers Ferry, they undertook more active scouting.

The Fight at Waterford

According to Briscoe Goodhart’s not-necessarily accurate, but always impassioned, account of the Loudoun Rangers, Lt. Slater had been absent for several days sick, but returned to camp at the Waterford Baptist Church on the evening of August 26, 1862. Because of the small number of men in the camp – only about 20, with half being new recruits – the First Sergeant was having difficulty mounting the guard. Slater, “a very popular officer” according to Goodhart, saw the sergeant’s predicament, and cast himself into the breach, acting as corporal of the guard, as well as Officer of the Day. At about 3:00 in the morning of August 27th, Maj. Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion, Ewall’s Brigade,Virginia Cavalry, having dismounted and made their way across the fields undetected, reached the Rangers’ camp. Hearing an unusual noise, the men rushed out of the church, and Slater hastily formed them in line. Slater’s command: “Halt, who comes there” was met with a volley of shot, which wounded over half of those in front of the church.

Slater himself was shot in the temple, shoulder, chest, arm, and hand. The Rangers fell back into the church, and Slater retained command until the loss of blood rendered him unable to continue. The fighting continued until the Rangers ran out of ammunition. Consulted by his second-in-command, Slater (covered with blood), dictated a reply to White’s demand for capitulation, which conditioned their surrender on all being paroled and released on the spot, and the officers to retain their sidearms. Slater’s terms were accepted at once by Maj. White. Those who could went out and formed a line in front of the church, where they were paroled. White then went inside; upon seeing Slater, he reportedly said to him, “I am sorry to see you so dangerously wounded, Lieutenant.”iv

Two local physicians attended to Slater immediately after the fight. Dr. John J. Henshaw of Lovettsville (a delegate to the Restored Government of Virginia in 1863, and State Treasurer of the Unionist government), later stated in an affidavit that he had found Slater seriously wounded. “While the wounds of the hand and head were sufficient to cause great pain and probably result in permanent disfigurement, the fracture of the right arm as the most serious demanded the utmost skill. He was under the impression that amputation would be necessary, but a strong constitution, youth, good habits and the best of medical attention and nursing enabled Lieut. Slater to rally and save his arm.”

Another comrade, Milton Gregg, related essentially the same version of events as Dr. Henshaw. Gregg stated he sent for Dr. Thomas Bond (of Waterford) who had fled to Point of Rocks, to come back to Waterford and care for the wounded. Gregg said the doctors discussed “the amputation of Slater’s right arm as the only means of saving his life,” and added: “For a while it was considered doubtful whether he would not die from the effects of his wounds.”

Slater was taken to local residences for about three weeks, until he could be taken to his father’s farm. About two weeks later, he was taken to his old college town where he had friends, undoubtedly with the idea of getting him out of the war zone. That town was Gettysburg. As the stories tell it, while recovering in Gettysburg, he was again wounded – but this time more benignly, by Cupid’s arrows. His “guardian angel” who tended to his wounds was Mollie Yount, sister of Slater’s college friend Ephraim Yount, and later Luther’s wife.v

Meanwhile, in late November 1862, being partially recovered from his wounds, but still considered unfit for field duty, Slater was appointed as the U.S. Provost Marshall at Point of Rocks, Maryland. By this time, those Rangers who had surrendered and were paroled at Waterford, had been exchanged and returned to duty. Slater’s extensive knowledge of the area rendered him capable of determining who should be permitted to take goods through the blockade.

Taylor Chamberlin’s book Crossing the Line reports that, in his capacity as Provost Marshall, Slater served under Col. Lafayette Baker, a colorful character who was the Provost Marshall of Washington, the head of the National Detective Police, the de facto head of counter-intelligence for the federal government, and the founder of the U.S. Secret Service.

On February 16, 1863, Slater submitted his letter of resignation, and on February 19, 1863, he was discharged from the Army because his right arm was completely disabled, and, according to a military surgeon, he would not be able to resume his duties. In June of 1864, Slater was granted a disability pension for “GWS” (gun-shot wound) of the right arm, in the amount of $8.50 a month.

Goodhart later wrote of Slater that “he was not only obeyed and respected, but loved by all — a large, physically well-built man, a true type of American soldier, and brave as a lion.”

Gettysburg

Meanwhile, having returned to Gettysburg and still recovering, Slater responded to the emergency calls issued on June 15, 1963 by President Lincoln and by Pennsylvania Gov. Andrew Curtin, for volunteers to repel the Confederate invasion which was coming up into Pennsylvania from the Shenandoah Valley. The defense of Harrisburg was the top priority of Gov. Curtin and Gen. Darius Couch, the newly-appointed commander of the Department of the Susquehanna of the Army of the Potomac.

Despite the fact that his arm was still in a sling, Slater reenlisted on June 16, and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in Company A of the 26th Emergency Volunteer Regiment, and helped to lead a newly-enlisted group of students in attempting to delay the Confederate troop movements.

Company A was in fact the first unit to be formed in response to Lincoln’s and Curtin’s call; it was initially composed of 61 young men from Pennsylvania (now Gettysburg) College and the Lutheran Theological Seminary, and 21 men from the town of Gettysburg.

Other enlistees in Company A were Cpl. David Yount (Slater’s future brother-in-law), Samuel Pennypacker (later Governor of Pennsylvania), and H.M.M. Richards (grandson of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg), who later graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, led the Pennsylvania German Society and other historical societies, and wrote extensively about German-Americans in the French-Indian War and the Revolutionary War.

The Gettysburg students were mustered into the Union Army in Harrisburg, underwent but a few days of rudimentary training, and on June 23, were deployed with the 26th Regiment, numbering 743 men, to Gettysburg. Other volunteer regiments were deployed to protect the railroads in York County, and the bridge crossing the Susquehanna at Wrightsville, south of Harrisburg (where present-day U.S. Route 30 crosses the river between York and Lancaster).

On June 26, as the young men of the 26th were positioned west of Gettysburg along the Cashtown (Chambersburg) Turnpike and adjacent roads, along came Jubal Early’s Division of Ewell’s Corps. approaching from the west. On that morning, Early sent a brigade of Georgia infantry and a battalion of Virginia cavalry down the turnpike toward Gettysburg. In the van was Elijah White’s 35th Va. Cavalry. When White’s experienced cavalry met the green militia volunteers, it was no contest. The regiment scattered and ran; 175 were taken prisoner. There were no deaths.

As Chamberlin and Souders note: “His [Slater’s] presence assured that there would be Loudouners on both sides when the first shots were fired at Gettysburg that afternoon.”

This was an insignificant skirmish which had very significant consequences; indeed, some identify this as one of the reasons that the decisive battle of the Civil War is now known as the Battle of Gettysburg – rather than, perhaps, the Battle of Susquehanna or Harrisburg.vi

The previous days’ experience in routing the green militia forces contributed to the over-confidence of Confederate leaders and the June 30 decision of Gen. Henry Heth to attack Gettysburg, in belief that he would only be facing inexperienced militia troops. As they headed toward Gettysburg in search of shoes and provisions, Heth and his men assumed that the troops that they spotted on the ridges west of town were mere militia soldiers. It was surely an “uh oh” moment, when Heth’s troops realized they were facing regulars of the Army of the Potomac – and the Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point in the War, was on.

What was Slater doing for the rest of the war?

According to a notation in his service records, he was detailed to the Signal Corps by Maj. Gen. D. N. Couch, the Commander of the Department of the Susquehanna. A Gettysburg college history says that three men from Co. A were detailed to the Signal Corps: two of them being Luther Slater and his future brother-in-law, Cpl. David Yount. Slater’s service records show him being mustered out of the regiment on July 30, 1863.

One of Slater’s obituaries (the Washington Herald) stated that he served in the Hospital Corps for the remainder of the war.

Goodhart’s history of the Loudoun Rangers reports that in November 1863, while there was an effort being made to bring the Loudoun Rangers up to battalion strength, Slater served on a volunteer basis as the acting Captain of the newly-formed Company C (which had been formed starting in July in Lovettsville by Charles F. Anderson, who died in a fall at Bolivar on Nov. 1). Later in November, Means ordered Companies B, C, and D consolidated into a new Company B, which numbered about 60 men. (Slater’s temporary leadership of provisional Company C may be why he was referred to as “Captain Slater” later in life.)

Cavalry officer, Provost Marshall, Signal Corps, Hospital Corps: Slater was a versatile individual. We know not exactly all of what he was doing during the last two years of the war, but judging from the impressive collection of those writing letters of recommendation for his appointment as a hospital steward in 1867 (see below), he somehow had established connections with a number of senior Army flag officers.

In November 1864, Luther married his “guardian angel” Mollie Yount at Gettysburg, with Prof. F. A. Muhlenberg officiating. They had their first child, Effie, in September 1865.

After the War

By the Spring of 1865, Slater and Mollie had returned to Lovettsville. On June 1, 1865 – the first post-war election in Loudoun County — he was elected one of four Constables for Lovettsville. Then on July 3, 1865, Luther Slater was appointed as Postmaster in Lovettsville, a political-appointment which he held until April 9, 1867.

In 1867, Slater enlisted as a Hospital Steward in the U.S. Army, thus beginning of a 42-year civilian career at the War Department headquarters in Washington. He was recommended by three U.S. Army Generals and a United States Senator:

Brig. Gen. John W. Geary: then-Col. Geary occupied Lovettsville and northern Loudoun County in February 1862 for about a month; was greeted with enthusiasm in Lovettsville and northwest Loudoun, but received a less-than-warm welcome in Leesburg.

Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler: well-known politician and Union General; occupied New Orleans and Norfolk, action during the siege of Petersburg; before war, was in Massachusetts legislature; after the war, was a five-term U.S. Congressman, and then Governor of Massachusetts.

Brig. Gen. James A. Eakin: Assistant Quartermaster of the U.S. Army; served on the Military Commission that tried the Lincoln conspirators at Ft. McNair. (He recommended clemency for Mary Surrat, based upon his Christian principles, but was overruled by the full Commission.)

United States Senator Waitman T. Willey: Unionist Senator from Va. July 1861-March 1863; elected Senator from W. Va. in 1863 as a Unionist; Republican Senator from W. Va. 1865-1871.

Slater was detailed to clerical work in the Office of the Surgeon General in Washington. In the late 1870s he was a clerk in the Records and Pensions Office, which later became part of the Office of the Adjutant General. He was rapidly promoted, and worked closely with the colorful and controversial Fred C. Ainsworth, head of the Record and Pension Office, and later The Adjutant General and Military Secretary. Ainsworth is known for his insistence on the integrity of original records, especially muster rolls, and his establishment of the card-file system used by the War Department to compile service and pension records for veterans of the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. This system, still used today, involved transferring information from the original service records and hospital records to index cards, which greatly expedited the processing of pension applications from veterans and their widows and children.vii

Re-Mustered in, twenty years later

Slater’s military records reveal a strange series of events occurring in the 1880s, reflecting the ad hoc nature of the original formation of the Loudoun Rangers. On January 23, 1883, Slater, now at the Surgeon General’s Office, filed an “Application for Certificate in Lieu of Lost Discharge.” In a sworn statement, he said he had been discharged on or about February 18, 1863 at Berlin, Md., but that his Discharge Certificate was lost or destroyed on or about the 26th of June, 1863, near Gettysburg. “I was there 2nd Lieut., Co. A, 26th Reg. Pa. Vol. Militia; the reg. was operating in vicinity of Gettysburg; the discharge was in my baggage; the train in which the baggage was, was burned by the enemy.”

When the Army started investigating, they also discovered that there was no muster-in record for Slater – or for any of the Loudoun Rangers. (Captain Means was not a military man, and wasn’t familiar with military record-keeping; and whatever records were created of the initial enlistments and muster-in in the summer of 1862, were lost during the Harpers Ferry breakout in September of that year.)

The Army’s solution was that on February 1, 1883, the Assistant Adjutant General ordered an “office muster-in” for Slater, to date retroactively from June 20, 1862. On February 2, a Muster-In Roll was created for Slater. Under “Remarks,” it was written: “Being unable to procure the original muster in roll this one is made from the best information obtainable, and, is an official muster.” It was signed by the Assistant Adjutant General. At the same time, to deal with his discharge, an Extract of Special Orders No. 49, Headquarters, Middle Department, 8th Army Corps, dated February 19, 1863, was provided, showing that Slater had been honorably discharged. (The same procedure for an “office muster in” was also performed for other former Loudoun Rangers.)viii

Similar confusion arose three years later, in February, 1886, when Slater filed for an increase in his disability pension. At this time another search for muster rolls of the Loudoun Rangers was undertaken, and the result was, again, that no evidence of the original muster-in from June 1862 could be found. The Adjutant General’s Office sent Slater a copy of his honorable discharge, and informed him that his record had been completed by showing him mustered in on June 20, 1862. The “Certificate in Lieu of Discharge” identified Slater as “formerly a 1st. Lt. in Co. A, 3d Regiment of W.Va. Cav, Independent Loudoun Rangers.”

Why West Virginia? By this time, the War Department had apparently decided to classify the Loudoun Rangers as part of the 3rd Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry. This had always been the case from the standpoint of the Restored Government of Virginia, which regarded the Loudoun Rangers as part of the 3rd Virginia Cavalry; the newly-created state of West Virginia (1863) also treated the Loudoun Rangers as a detached company (Co. F) of the 3rd W. Va. Cavalry. ix

Slater seems to have accepted this designation. In his initial application for membership in the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) in March 1892, he listed his service as with the “Co. A., Loudoun Rangers, Va. Cav.” but then by October of that year, he is listed as “Independent Battalion, West Virginia Cavalry.” The West Virginia Cavalry designation for Slater remained in use up through the MOLLUS circular published at the time of his death in 1909.

Post-war personal, church, and fraternal life

As we noted, Luther and Mollie Slater had moved to Washington City in the fall of 1867 (his uncle William Slater and cousins Isaac and William Slater were already living there).

In 1871, tragedy struck. Mollie gave birth to their second child, a son David, on April 8, 1871. She died about seven weeks later, on June 3, in Washington, and the infant David died nine days later, on June 12.

Mollie and her infant son are both buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg, in the shadow of the monument commemorating Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Three years later, Slater re-married, to his cousin, Margaret Prentice Slater. A few years after that, he built a handsome brick house at 442 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. in Washington, next to a home built by Isaac Slater a few years earlier. Both houses are still standing today.

In Washington, Luther Slater was a founding member of the Lutheran Church of the Reformation on Capitol Hill, and he was probably instrumental in obtaining, from the War Department, use of an old Army barracks as Reformation’s first place of worship – located at the site of the present-day Capital South Metro station. Worship began in the old Barracks building in May 1869, although Reformation’s founding members had been meeting as early as 1866 or 1867. The congregation was formally organized with a pastor appointed in October 1869. “Captain and Mrs. Luther W. Slater” are listed first among the names of those associated with the church at this time; also listed is his brother-in-law David Yount, Luther’s uncle William Slater, and uncle William’s sons I.C. (Isaac) Slater and William F. Slater.

Slater served as an elder and a trustee of that church, and also as the congregation’s treasurer and Sunday School Superintendent. He was forced to resign from the latter position in 1875 because of a “weak throat.” He also served on the Farming Committee of the Lutheran Home for the Aged.

Around 1880, Reformation appointed a Building Committee to look for a new church home to replace the old Barracks church. Luther Slater was appointed to that committee. In January 1881, the church purchased a property at Pennsylvania Avenue and B St., and a new church was built there, which was dedicated in 1883. That building served the congregation until 1933, when it was demolished to make way for the expansion of the Library of Congress and the construction of the Adams Building, with the new church building being located on East Capitol Street, across from the Folger Shakespeare Library, where it stands today.

During 1907, “A brass pulpit was dedicated in the memory of Mr. I. C. Slater, elder and Sunday school superintendent,” and somewhat later, “A brass lectern was presented in memory of Mr. L. W. Slater, elder and Sunday school teacher,” according to a church history.

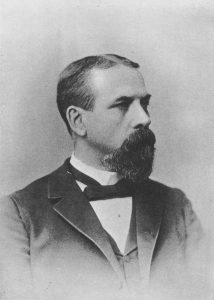

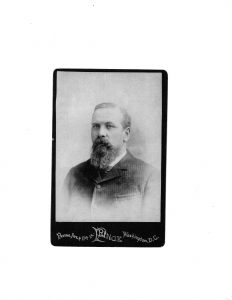

Portraits of Luther and Isaac Slater were located at the church in 2012 through the efforts of Mr. George Hutchison, and after their discovery, they were hung in the church’s fellowship hall, having been “restored to their rightful place,” in Mr. Hutchison’s words. The portraits are now on display in the church library.

Slater was also a founding member of the Freedom Lodge No. 118 of the Masonic Order in Lovettsville right after the Civil War, and served as its Secretary from 1965 to 1967. Its founding members were almost all Unionists.

In 1888, Slater was listed as a member of St. John’s Lodge No. 11 in Washington, D.C., and he was also a member of the Masonic Veterans Association at that time. He does not appear to have remained active in the Masons or the Veterans Association.

In 1892, Slater was received into the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), the organization of Union officers who had served in the Civil War. He was elected to membership as an “original companion” of the District of Columbia Commandery of the Loyal Legion on December 7, 1892, and remained a companion for the rest of his life.

Slater died of a sudden illness in 1909. In the record of deaths and funerals at Reformation Lutheran Church, after the entry marking Luther Slater’s death, there is the simple notation: “A good man.” In an obituary in the Washington Herald, Adjutant General of the U.S. Army Fred Ainsworth described Slater as “most faithful,” and said that “his loss to the Department will be most difficult to replace.”

A few years after his death, an address that had been written by Luther Slater was read at the 50th Anniversary Reunion of the Loudoun Rangers, held on August 24, 1912 at Taylorstown; the address, read by the Rev. Dr. John Weidley of the Reformation church, was described in a newspaper account as “a rare treat for all present.” 500 people were in attendance, including Confederate veterans.x

Slater was buried in Lovettsville Union Cemetery, along with his second wife Margaret, his daughter Effie Hickman from his first marriage, and his grand-daughters Louise Hickman and Clara Hickman.

In November 2008, the Military Order of the Loyal Legion honored Luther Slater by sponsoring the repairs and the rededication of his gravesite monument in Lovettsville Union Cemetery.

Endnotes:

i Two other commissioned officers in the Loudoun Rangers, Charles F. Anderson and Robert Graham, are buried in Waterford. All the other Union officers, including Loudouners who served in the Potomac Home Brigade, are buried out-of-state.

ii Primary sources on the Loudoun Rangers are records of the National Archives. The most important secondary sources are (1) Briscoe Goodhart’s 1896 History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers, (2) the thoroughly researched and documented 2011 account by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders, Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County Virginia, and (3) Lee Stone’s The Independent Loudoun Rangers: The Roster of Virginia’s Only Union Cavalry Unit (Waterford Foundation 2016), with Forward and Appendix by Edward Spannaus.

iii Slater was one of 28 members of the New Jerusalem congregation to enlist over in Company “A” of the Loudoun Rangers, according to research done by the late Pastor Mike Kretsinger.

iv Interestingly, both Elijah White and Luther Slater had also attended church-sponsored colleges out of state. White first attended Lima Seminary in western New York, a Methodist school which eventually evolved into Syracuse University. He then spent two years at Granville College in central Ohio (an area into which many Loudouners had transplanted themselves). Granville was a Baptist college which later became known as Denison University. In the pre-Civil War period, Granville College was a hotbed of anti-slavery sentiment – which probably would not have been to Elijah’s liking. It is likely that Slater and White were the only two men at the Waterford fight who had been to college, and, given their course of study, it is possible that both were originally preparing to enter the ministry.

v Mollie (Mary Ann Elizabeth) Yount was the daughter of Israel Yount, the proprietor of the Washington House Hotel in Gettysburg. Today the Lincoln Diner occupies the site of the old Hotel.

vi Gettysburg was not a major objective of the Southerners. The CSA plan was only to obtain supplies in Gettysburg (particularly, shoes), then to cut the railroad at York, and then to proceed toward Harrisburg both from the west, and also from the southeast via York and Lancaster. to prepare the way for the capture of the state capital, on the way to Baltimore and to Washington (or, as Dennis Frye, chief historian at Harpers Ferry National Park suggests, Philadelphia).

vii Gen. Ainsworth was also known for his confrontation in 1911 with Army Chief of Staff Leonard Wood and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, which resulted in Ainsworth being court-martialed. Ainsworth was a leader of the “traditionalist” faction within the Army and the War Department, who resisted the reforms championed by Secretary of War Elihu Root which resulted in the creation of a General Staff in 1903. Under the reorganization, the functions of the Adjutant General’s office and the Record and Pension Office were combined in 1904 under the new Military Secretary, who was Ainsworth. In 1907 Congress restored the Office of The Adjutant General (OAG), with Ainsworth as its head. Slater, as a top aide to Ainsworth, stayed with him during these various reorganizations.

viii The records of the “office muster in” are found in Slater’s Volunteer Service file at the National Archives: 1110 V.S. 1883, Record Group 94, Entry 476; Walz 186 – ‘67, filed with W 463 – V.S. ‘62.

ix Records of the Adjutant General of West Virginia. For more on West Virginia’s relation to the Loudoun Rangers, see “The Strange Case of the Disappearing Cavalry Captain” in the Lovettstville Historical Society newsletter, September 2018.

x Despite extensive efforts, the author has been unable to locate a copy of this address.