By Edward Spannaus

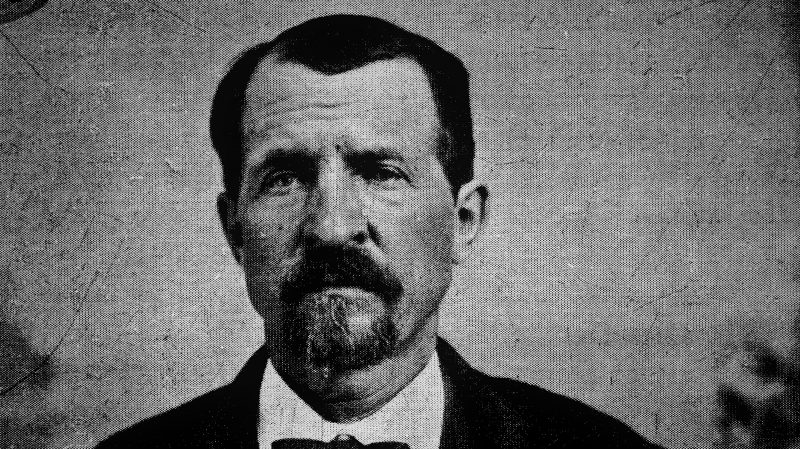

The Charles Johnson who featured in the fracas following a Republican event in Waterford in November 1888 was no stranger to conflict – be it of the military or political sort. In post-Reconstruction Loudoun he was known as a staunch Republican at a time when most of the County was Democratic, but long before that, during the Civil War years, he was publicly known as an outspoken and headstrong Unionist. Unknown except to a few, was that during the war, Johnson was also a leader in a clandestine spy network in the Lovettsville area which was reporting to the U.S. Bureau of Military Information (BMI) at Harpers Ferry.

This network was discovered in recent years by Taylor Chamberlin and John Souders when they were researching their 2011 book Between Reb and Yank, a history of the Civil War in northern Loudoun County.[i] And, as is common in the espionage business, there were others involved who questioned Johnson’s loyalty to the Unionist cause.

Exile and Scout

Charles Warren Johnson, born in the Lovettsville area in 1831, came from a prominent Maryland family; his great-grandfather was a Colonel in the Revolutionary War and a brother to Thomas Johnson, the first Governor of Maryland under the revolutionary government. Charles’ father, Robert Johnson, was one of only eleven Loudouners who voted for Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 elections; he was rewarded by being arrested by rebel soldiers in August 1861 and held for several months in a Confederate jail.[ii]

A few months earlier, during the secession referendum in May 1861 when pro-secession soldiers were stationed at the polls in Lovettsville, Robert’s brother-in-law Jonah Potterfield “raised a Confederate flag in front of his house, only to have his nephew, Charles W. Johnson, cut it down.” Between Reb and Yank continues the story: “The soldiers arrested Johnson and forced him to put up another pole. Potterfield produced a new flag and asked the soldiers to provide him with guns to guard it.”

After secession, Loudoun was occupied by Confederate troops, and with military-age men being conscripted into the rebel army, Charles Johnson went into exile across the river in Maryland, as did numerous men from northern Loudoun, and he began working with the Union Army almost immediately, as did members of Capt. Armistead Everhart’s militia company, serving as guides for Union soldiers on raids into Virginia.

At the end of October, an opportunity presented itself, when Jonah Potterfield crossed over to Harpers Ferry on an errand. He was seized, likely by Charles Johnson, Armistead Everhart, and one or more others, and handed over to the authorities, where Potterfield was put before a military tribunal. Among the witnesses was Johnson, who testified about the flagpole incident. Potterfield was convicted and sent to Fort McHenry in Baltimore, and then to Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor as a “high value” political prisoner.

It would seem that by December, Johnson was on familiar terms with Col. John W. Geary of the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry who had arrived at Harpers Ferry in July and was to occupy Loudoun County in 1862. When Johnson’s second son was born, on Dec. 1, 1861, he named the boy Robert Geary Johnson.

Along with Sam Means, Charles Johnson was one of the guides leading Geary’s troops into Loudoun County at the end of February 1862, and into Lovettsville on March 1, where they were warmly welcomed.

We don’t know exactly what Johnson was doing during the Spring and Summer of 1862, but we do know that he was employed as a guide by McClellan’s forces after the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. On October 1, he guided Gen. Nathan Kimball’s brigade from Bolivar Heights near Harpers Ferry, on a reconnaissance mission toward Leesburg.

On October 3, a request was submitted from Kimball’s brigade that Johnson be paid for “valuable” service during the Leesburg raid, in which he “showed himself not only a good guide but a valiant soldier.”[iii] On October 19-21, he was one the guides for the 10th Maine on an unsuccessful mission to attack a Confederate observation post on the Short Hill, and then on a scout through Bolington and Lovettsville.

Johnson raises suspicions

That part of Johnson’s activities in October is fairly clear, but other reports about Johnson from that same time period make matters more confusuing. The most curious of such reports is a letter from John Babcock, Alan Pinkerton’s former deputy, written from near Fredericksburg at the end of December 1862.

A little background: As is well-known, President Lincoln sacked Gen. George McClellan on November 5, 1862, while McClellan was encamped at Warrenton, having passed through Lovettsville about ten days earlier. Along with McClellan went his secret service chief, Alan Pinkerton, and all of Pinkerton’s files and his civilian detectives.

McClellan’s replacement, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, lost all of Pinkerton’s secret service except for one enlisted soldier, Private John Babcock. Babcock was a talented map-maker and architect from Chicago, who was asked by Burnside to prepare a report on the condition of the secret service – an impossible task, since Pinkerton had taken all his files with him. According to Edwin Fishel’s ground-breaking book on Civil War intelligence, The Secret War for the Union, this left Babcock without an assignment. So Babcock came up with a self-assignment: a counterintelligence surveillance of Lovettsville’s Charles Johnson.[iv]

In a December 31, 1862 letter, Babcock calls Johnson a “spy” who has been “employed by the rebel government to operate within our lines.” He describes Johnson as “said to reside near Lovettsville, Va.,” and he says that prior to Johnson’s employment by the Confederates, Johnson was employed by the Union Army in Maryland since October, and that Johnson had also been employed by “E.J. Allen” – the pseudonym for Pinkerton. He characterizes Johnson’s conduct while in the employ of the Union Army as “very suspicious.” Babcock says that Johnson was discharged from the Union Army around November 10, and that he was reported to have returned to his home.

Babcock goes on to say that on “the 15th inst.” – presumably December 15 – “I saw Johnson at Falmouth Station, Va., [across from Fredericksburg] for the first time since his discharge, mounted on a U.S. horse and having on a partial U.S. uniform.” He says he carefully observed Johnson day after day, which “confirmed my suspicions as to his character and purpose.” He didn’t want Johnson to be arrested, since he hoped to gather more evidence concerning his activities. But, unfortunately, Babcock says, Johnson was captured by a squad of rebel cavalry near Ocoquan, along with “a quantity of sutlers stores,” on the 19th of December.

How does Babcock explain that a rebel spy was taken captive by rebel forces? He says he has no doubt that Johnson himself was in on it, and that the arrest was a ruse carried out for the purpose of getting Johnson through the lines with whatever information he had, as well as for obtaining the supplies he was carrying.

To confuse matters even more, Babcock says that he had since learned from a reliable source, that on the 22nd, Johnson was at home near Lovettsville and that he then left for Leesburg. Should Johnson show up again, Babcock declares, there is enough evidence to arrest him as a rebel spy.

Babcock seemed to regard Johnson as exemplary of a broader, serious problem that the Army had with civilian sutlers (travelling merchants) and smugglers, who used their connections in Washington to get passes allowing them to move through military lines and hawk their merchandise. These characters deserve serious investigation, Babcock asserts, but he indicates that he is hampered in this regard, by the fact that Pinkerton took all his investigative files with him when he left.

There is an apparent problem with the dates here. Although Babcock says that he observed Johnson hanging around the Union camp at Falmouth in mid-December 1862, and reports that Johnson was captured by Confederate forces on Dec. 19, we have other indications that Johnson was taken prisoner in Lovettsville in late November of 1862. Local farmer Christian Nicewarner wrote in his diary for November 25, 1862, that “Charles Johnson taken prisoner.”[v] Did Babcock mean November instead of December? It’s possible, but his letter was a report on his activities for December, not November.

That Johnson was in prison during December is also indicated iny a letter by a Confederate officer, Major E.V. White’s superior Gen. Gumble Jones, sent to the commanding officer at Castle Thunder prison in Richmond, naming certain “dangerous” prisoners who should not be released or exchanged. Among these was a prisoner named Johnson who had been sent to Castle Thunder on November 28, and who “had many serious charges made against him” and should not be released under any circumstances.

Apart from the discrepancy in dates, we have here both a Union intelligence officer, and a responsible Confederate flag officer, both warning that Johnson is working for the other side. This ambiguity – to put it mildly – continued throughout the war.

Johnson was released from Castle Thunder around April of 1863, after four or five months of confinement. Chamberlin and Souders, in Between Reb and Yank, point out that Johnson was in danger of being hung at Castle Thunder, but that he credited quick action by his neighbor Samuel W. George for his survival and release. Sam George, accompanied by Johnson’s sister-in-law, went to Harpers Ferry to brief Gen. Geary on the situation. Geary ordered that two secessionist hostages be taken to secure Johnson’s safe release. The gambit worked, and Johnson was released.

Johnson himself later testified, in his Southern Claims Commission case, that he had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy as a condition of his release, but that he had made an arrangement with General Winder, the commander of Castle Thunder, that he would go home to his family, and that “I should not interfere in the war.”

Lovettsville’s secret spy network

Johnson next comes to our attention in May 1864. More than a year earlier, a real military intelligence service had finally been created: in early 1863, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, Commander of the Army of the Potomac, had brought in Col. George Sharpe, a former lawyer from New York, to head the newly-created Bureau of Military Information (BMI). Sharpe’s deputy was John Babcock, now a civilian, who flourished in his new position. For his second assistant, Sharp brought in Capt. John McEntee of New York, who was to head scouting operations, among other things. McEntee also established “branch offices,” including one at Harpers Ferry.[vi]

In the Spring of 1864, as part of his information-gathering in the Shenandoah Valley, McEntee came across a loose network of Unionists in the Lovettsville area, which described as “a Union league or association of Union people over in Loudoun County who make every effort to obtain all intelligence regarding the enemy.”[vii] McEntee said they were operating under an agreement with Gen. Jeremiah Sullivan, who had taken over command at Harpers Ferry in October 1863.

Chamberlin and Souders report that members of the “Union League” kept quiet about their work, even long after the war. However, they found references to the shadowy organization in other places, particularly in the records of the Southern Claims Commission, before which Southerners who could prove their loyalty to the Union, could seek compensation for war-time losses.

Lovettsville farmer George S. Wenner, for example, identified William F. Cooper as the group’s most prominent leader, followed by Tilghman Cooper, Gideon Householder, and Charles W. Johnson.

So now we have an alleged Confederate spy, Charles Johnson, named as a prominent leader of a Union spy network. What to make of all this?

Silas Kalb thought he knew what to make of it. In an 1874 letter to the Claims Commission, Kalb said that after Johnson’s return from prison in Richmond, Johnson’s home was visited frequently by rebel guerrillas. He described how he (Kalb) and a neighbor would lie in wait in the mountain near Johnson’s house, hoping to capture or shoot a notorious rebel [probably John Mobberly], who frequented Johnson’s house along with rebel soldiers. He also noted how a Federal deserter who had joined Mobberly’s gang, was captured at Johnson’s house, and was taken to Harpers Ferry and hung. (This is clearly a reference to “French Bill,” who was captured by Loudoun Rangers at Johnson’s house – or still-house — on November 30, 1864.)[viii] Kalb did allow as how Charles Johnson had used his influence with the rebels to get horses that had been taken from loyal men returned to them.

For references to his own loyalty, Kalb cited many Union officers, including Generals Max Weber and Sullivan, and also “Capt. McEntee of the secret service” – thus demonstrating his own familiarity with the command structure of those running the clandestine Loudoun network.[ix]

Was he, or wasn’t he?

Now, let’s see if we can make any sense of these contradictory reports. It appears that the best evidence is the Southern Claims Commission’s handling of the Charles Johnson case in 1877, where the commissioners seemed to have no doubt as to Johnson’s loyalty — despite having before them Silas Kalb’s letter to the contrary. Taylor Chamberlin notes, in his summary of the SCC file, that the testimony was taken in Washington, not locally, which is unusual in such as small case – only a $400 claim. The witnesses were William H. Krantz, who had himself been a scout who was imprisoned by Confederate authorities as a spy; Lovettsville farmer George H. Wenner; and C&O Canal employee David Davis, who testified about Johnson’s horse being a valuable animal that was taken to Harpers Ferry. Krantz said he knew Johnson as a scout in Federal service, and that Johnson had been arrested and taken to Castle Thunder. Wenner, as mentioned above, testified that Johnson had gone to the other side of the river, to Maryland, and then went with the Army. Both testified that they had never heard anyone questioning Johnson’s loyalty.

Other witnesses whom Johnson proposed to call to testify on his behalf – but whom the commissioners apparently deemed unnecessary — were: Gen. Geary, Peter A. Fry, Luther H. Potterfield, Thomas J. Cost, and Samuel W. George.

The commissioners appear to have given great weight to the fact that Johnson was employed as a scout for the Union Army, and that another scout (Krantz) had confirmed this, and also that Johnson had been taken prisoner by the rebels. They directed that $150 of his claim to be paid to Johnson by the Treasury.

What is also notable is those who were NOT witnesses: neither Silas Kalb, nor John Babcock. In other SCC claims cases, the commissioners undertook an extensive investigation before actually hearing the case, including seeking records from the War Department. In a case involving the secret service and the BMI, it is hard to believe that the commissioners had not made some effort to determine whether the Army regarded Johnson as loyal; it is just as hard to believe that they had not made up their minds before Johnson’s claim went to a hearing, given the lack of any adverse witnesses being called.

However, we should note that there had already been a lot of testimony concerning Johnson a couple of years earlier, in the claims case of Johnson’s neighbor Samuel W. George, during which extensive testimony was taken in 1873-75.[x] In the George case no one seems to have given adverse testimony against Johnson, except for Charles J. Brown, who didn’t question Johnson’s loyalty, but who claimed that Johnson was boasting about his success is promoting Sam George’s claim, which he was allegedly going to get part of any monies paid out.

Robert Booth described how he and Johnson were sent across the river by Col. Geary in the Fall of 1861 to get information on the rebel forces. Samuel George himself testified about Johnson being a Federal scout, and how the Southerners “arrested Johnson and were dragging him about.” And former Loudoun Ranger Capt. Sam Means said that Johnson was one of the most loyal men we had.

So it seems that the SCC commissioners and investigators likely had heard quite a bit about Johnson before they commenced the hearing in his case.

As for Kalb, we presume that he was reporting in good faith what he had seen: rebels and renegades such as Mobberly hanging out with Johnson at his house and/or his still-house. What Kalb of course could not know, is whether Johnson’s apparently hospitality toward the enemy was being done with the knowledge and approval of the military authorities and the BMI. Just because Kalb and Johnson were in the same clandestine network, did not mean that everyone in the network knew what everyone else was doing, and why.

Regarding Babcock, author Edwin Fishel, himself a career intelligence officer, puts Babcock’s December 1862 letter in a revealing context. He portrays Babcock as floating without an assignment or mission, in the months between Pinkerton’s departure in October 1862, and the formation of the BMI in early 1863 – to the point that Babcock made up his own assignment, which was surveillance of Johnson.

Fishel characterizes Babcock’s detailing of his counterespionage surveillance against Johnson as “a thinly-disguised way of pointing out that he had spent nearly two months not doing the positive-intelligence job he was supposedly hired to do.”[xi] In this light, we could conclude that Johnson was not the actual subject of Babcock’s letter, which was really about the vacuum of intelligence concerning the enemy, and the wasting of his own talents. Once the BMI was formed, Babcock proved himself to be a brilliant intelligence officer, who came to know the Confederate command structure and “order of battle” far better than anyone in the Army of the Potomac.

Of course, this still leaves open the question of what kind of deal did Johnson make when he was released from Castle Thunder? He himself said that he promised to go home and not interfere in the war. He admitted only to hauling corn and wheat for the Confederates on two occasions. However, his conduct after his release suggests that he had been “turned” and was aiding the rebels by reporting on local Unionists. Of course, he could have been turned back yet again, and may have been reporting to the Union Army on the rebels and renegades he was hosting at his house.

Even more intriguing is Babcock’s timing of Johnson’s activities around Burnside’s encampment at Falmouth, near Fredericksburg, in December 1862 – weeks after he had reportedly been arrested in Lovettsville. Either Babcock had the dates wrong, or Johnson was released so that he could infiltrate Union lines while under the cover of a sutler and smuggler. And reading between the lines of Babcock’s letter, his reliance on mere observation of Johnson was a product of the lack of intelligence records — which Pinkerton had walked off with. Babcock would have no way of knowing about Johnson’s previous role with the secret service.

In summing the matter up, Chamberlin and Souders write that “We may never know what happened to Johnson, seemingly a loyal and capable Union scout, during the last two months of 1862.” They review some of the possibilities: that it was a case of mistaken identity by Babcock, that Babcock was misled by misinformation from one of his sources; or that Johnson was turned by his rebel captors and sent back into Union lines. As to his consorting with rebel guerrillas, and allegations of smuggling, Chamberlin and Souders conclude that “Charles Johnson was but one of many in north Loudoun, who had to walk a crooked line to survive.”[xii]

Post-war life

Another indication of Johnson’s loyalty to the Union, was that he remained an active and outspoken Republican political leader for the rest of his life – this at a time when the County and the State were controlled by the Democratic machine. Johnson defended his political principles, and perhaps his local political privileges, to the point of violence on occasion.

We have seen above, the story of the “jollification” in Waterford after the November 1888 election.

Another incident which took place a few months later, involved the postmaster appointment in Lovettsville in March 1889, shortly after Republican Benjamin Harrison succeeded Democrat Grover Cleveland as President. At that time, a change of the party in power also meant a change of postmasters, one of the prime patronage positions.

How this played out in Lovettsville, was reported in the Loudoun Telephone of March 22, 1889. The protagonists were Charles Johnson and Jacob Boryer, a one-time Loudoun Ranger, who was involved in some dubious commercial schemes later in the war involving the customs office in Berlin (Brunswick), which landed him in Old Capital Prison in Washington for a couple of months. (Boryer’s name is mis-spelled in the following article.)

AN UGLY FIGHT

All About a Postoffice

“There has been war in Lovettsville; at least there have been ‘rumors of war.’ These rumors, which may not be correct in details, indicate that Messrs. C.W. Johnson and J. Buryer, both Republicans, assisted by their sons, indulged in an ugly fight a few days ago. It is reported that Mr. Johnson met Mr. Buryer upon the street and accused him of being a party to a scheme recently worked, by which M. Chinn the democrat postmaster at that place resigned and a republican was appointed – presumably for the purpose of keeping the office in Chinn’s store. To this Mr. Buryer made certain admissions, whereupon Mr. Johnson berated him so severely that blows and a scuffle followed and very quickly the two were lying in the gutter with Johnson on top. The latter was proceeding to punish his adversary when Mr. Buryer’s son rushed up with a stone, with which he struck Mr. Johnson on the head, causing the blood to spurt in a stream from the wound. As this juncture Mr. Buryer was seen to get out his knife, but before he could use it the men were separated by others who had been attracted by the affair. All this happened in less time, perhaps, then it takes to mention it, but it was a serious and unfortunate affair. And it is hoped that the reports of it are exaggerated.”[xiii]

“Mr. Chinn” was probably storeowner Walter Chinn, who was postmaster from July 1885 to February 1889. The Chinn Brothers store was on the main street (now Broad Way, at the corner of Light Street). According to The German Settlement book,[xiv] Chinn was succeeded by one Samuel Beck, but for only a couple of weeks. On March 21, 1889 – probably a day or two after the Johnson-Boryer street fight — Luther Potterfield, a Republican, became postmaster and served for four years, until the next presidential election, when he was succeeded by Kenny Chinn. During the Civil War, Potterfield lived across the road from Johnson, and it was at Potterfield’s farm that the renegade Mobberly was ambushed and shot in April 1865.

We don’t know a lot about Johnson’s post-war life, other than that he was a farmer-businessman, and that he was active politically in Republican Party politics. (He was, for example, the delegate from the Lovettsville Magisterial District to the Republican Congressional District Convention in 1884.) He was also a trustee of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1878, when the Kalb family sold it the property on which Mount Olivet United Methodist Church is now located.

The following letter provides a laudatory view of Johnson, a viewed shared by many if not all in the Lovettsville community at the time of his death:

“A good man and citizen”

The following was published in a local newspaper in October, 1899:[xv]

Lovettsville, Va. Oct. 10th, 1899

CAPT. LYNCH — Dear Sir: Our community was greatly shocked on Sunday last by the news of the sudden death of Mr. Charles W. Johnson caused by injuries inflicted by a vicious horse.

Mr. Johnson was a prominent man in our district and well-known throughout the county. A republican since the civil war, he was an active and able political leader and was influential in the political circles of his party. Sincere in his party faith he was a hot partisan and had the courage of his convictions, perfectly fearless and outspoken in his opinions, he was not so considerate of the feelings of his opponents as he might have been, and perhaps often uttered words that for a time, rankled. But apart from this, while like all men he had his imperfections, Mr. Johnson possessed in an eminent degree the many good qualities that go to make up a good man and citizen, qualities that won and kept for him the respect and esteem of our community.

In his public relations he was honest and square, in his business transactions a staunch friend, and an open enemy incapable of striking from behind or stabbing in the dark or of revising petty malice, but after openly having out his quarrel was ever ready to “forgive and forget.”

In his home he was a devoted husband and father, and his house was the seat of free handed hospitality.

Generous and kindhearted he was ever ready to relieve distress and in him, his poorer neighbors have lost a benevolent and sympathetic friend. Notwithstanding the fact of its being the busiest time in an agricultural country, his funeral cortege was one of the largest ever known in our locality which proved how he was held in the respect and regard of his neighbors, and until this generation passes away Mr. Johnson will be remembered her as a brave kindly hearted gentleman, who despite of party rancor, was an honored influential and useful member of our community, and we believe that without an exception, the entire neighborhood extends the deepest sympathy to his family in its sad bereavement. E.V.C.

* * * * *

[i] Chamberlin and Souders, Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia (McFarland & Co., 2011), pp.251-252.

[ii] Ibid., p. 144.

[iii] Ibid., p. 367 n. 6.

[iv] Edwin Fishel, The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1996), pp. 262-273; Babcock letter to Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. J.G. Parke, Dec. 31, 1862, in Johnson’s Southern Claims Commission (SCC) file, provided by Taylor Chamberlin.

[v] The Nicewarner (Nisewaner) diary was first published in Yetive Weatherly’s book Lovettsville: The German Settlement (Lovettsville Bicentennial Committee, 1976), pp. 33-35.

[vi] William B. Feis, Grant’s Secret Service: The Intelligence War from Belmont to Appomattox (University of Nebraska Press, 2002), p. 197.

[vii] Between Reb and Yank, pp. 251-252; Feis, p. 263.

[viii] Chamberlin and Souders, p. 305.

[ix] Kalb’s letter, dated April 14, 1874, is in Johnson’s SCC file.

[x] Samuel W. George SCC case file.

[xi] Fishel, p. 273.

[xii] Chamberlin and Souders, p. 158.

[xiii] Article reprinted in Wynne C. Saffer, Loudoun Votes 1867-1966: A Civil War Legacy (Westminster, Md.: Willow Bend Books, 2002), p. 53.

[xiv] Weatherly, p. 65.

[xv] This article was transcribed and provided by Mrs. Fran Wire of George’s Mill. “Capt. Lynch” may have been William B. Lynch, the editor of the Washingtonian newspaper published in Leesburg. “E.V.C.” may have been Emory V. Chinn (1860-1939) of Lovettsville.