On June 4, the Loudoun County Heritage Commission will present to the County Board of Supervisors, its recommendations for new monuments and memorials on the Courthouse grounds. Among the Heritage Commission recommendations are that the County erect a Civil War Veterans’ Memorial which would – for the first time – recognize the role of Loudoun’s black and white soldiers who fought for the Union in the Civil War, in particular in the U.S. Colored Troops, the Loudoun Rangers, and the Potomac Home Brigade.

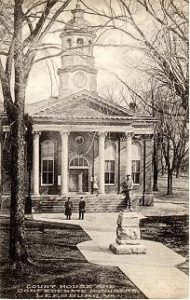

In September 2017, the County Board of Supervisors directed the Heritage Commission to review the full historic significance of the Courthouse grounds, and to make recommendations as to additional memorials, monuments and/or statues which would be appropriate “to fully reflect the history of the grounds, the County, and its citizens.” The Commission’s Recommendations and Historic Narrative to the Board are posted on the County website for the Board’s June 4 business meeting.

The 2017 initiative by the Supervisors came in the wake of the events in Charlottesville and elsewhere protesting the existence of statues honoring Confederate soldiers and officers in public locations in Virginia and in other Southern states. There were calls to remove the Confederate statue which was erected in 1908 from the Loudoun County Courthouse grounds.

Supervisor Geary Higgins (R-Catoctin), who put this initiative before the Board, explained it this way:

The intent of this item is to tell all of Loudoun’s Courthouse grounds history through a thoughtful, historic review process conducted by the Loudoun County Heritage Commission. It is Supervisor Higgins’ view that the Confederate soldier statue should stay where it is, but it should not stand alone on the courthouse grounds. We are always better off when we learn from each other and build on our understanding of our history. Loudoun’s unique history is our strength, not our weakness. We can’t learn from history if we hide it

Accordingly, the Heritage Commission was not asked to make a recommendation regarding the Confederate statue, but was directed to make recommendations for measures which would tell the rest of the story of Loudoun’s rich history and of the Courthouse itself.

Recommendations

The Heritage Commission’s recommendations are summarized as follows:

The Commission recommends that the Board:

- 1) accept the submitted research narrative … and publish the narrative on the County website for public information and comment;

- 2) allocate funds and direct staff to pursue National Historic Landmark status for the courthouse;

- 3) direct staff to prepare a proposal to name the old or new courthouse after Charles Hamilton Houston;

- 4) direct appropriate interdepartmental coordination to ensure that sufficient space for an interpretive “Path Toward Freedom” walk is reserved in the design of the new courthouse grounds; and

- 5) allocate funds and direct staff to coordinate a professionally facilitated community process to design and place memorials along the interpretive walk honoring Loudoun County’s path to freedom and justice.

The Commission’s specific recommendations, as embodied in its “Action Proposal,” are:

- Erect a Civil War Veterans’ Memorial to the U.S. Colored Troops,Loudoun Rangers, and Potomac Home Brigade

- Design and install a “Path Toward Freedom and Justice Walk” – The walk would serve as a chronological interpretive trail using markers, signs, sculpture, etc., to describe significant events and people associated with the courthouse. The trail could begin with the reading of the Declaration of Independence on the courthouse steps and terminate with a space for reflection on “the path forward.”

- Life and Liberty Memorial — This could be a sculpture, plaque(s) or marker(s). On August 12, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read by Loudoun County Sheriff Philip Noland at the door of the courthouse and the courthouse bell was wrung. Liberty had been won for some. At the same time, and for nearly a century more, the courthouse played a prominent role in supporting the lack of freedom for African Americans in the county. Enslaved men, women and children were sold to the highest bidder on the courthouse steps.

- Name the Old or New Courthouse after early Civil Rights Leader,Lawyer, and educator Charles Hamilton Houston

- Complete a National Historic Landmark nomination for the Courthousefor submission to the Department of the Interior – National Parks Service

Loudoun’s Union Soldiers

Of particular interest to those in northern Loudoun County, is the proposal to recognize those from Loudoun County who fought for the Union, in addition to the County’s long-standing recognition of its Confederate soldiers.

In its “Action Proposal,” the Heritage Commission summarizes its proposal this way:\

Findings: Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861 and was a Confederate state, home to the Capital of the Confederacy in Richmond. However, Loudoun County, by virtue of demographics and location, distinguished itself as the only part of a Virginia to muster units of soldiers to fight for the Union cause. The Loudoun Rangers were composed of 249 mostly-Loudoun men, formed in the Quaker village of Waterford and the German-American village of Lovettsville. It was led at the outset by Captain Samuel Means of Waterford and 1st Lt. Luther Slater of Lovettsville. The Union Potomac Home Brigade was formed to protect the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in late 1861. Recent research has identified 42 Loudoun men who served with this Unit comprised mostly of Marylanders. Many of these men had fled Loudoun County under threat by their overwhelmingly Confederate neighbors. And finally, because of recent scholarship, we know that at least 248 African American men, claiming Loudoun as their place of birth, fought on behalf of the Union as part of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Some of these men were enslaved and escaped to join the USCT, while many others were registered in Loudoun as “free negroes.” All most assuredly fought to end slavery and win freedom for loved ones and friends. Each of these 539 men who fought for the Union risked forfeiture of their families, homes and lives. This piece of history – so unique to Loudoun County – must be told and these veterans honored and memorialized as all other Loudoun veterans – in the same fashion and in the same sacred space on the historic courthouse grounds. Currently, no wreath is lain in memory of these veterans on Memorial Day, Veteran’s Day, and other memorial services due to the lack of a monument in their honor.

In the Commission’s 77-page Historic Narrative, the section on Loudoun’s Union soldiers reads as follows:

LOUDOUN’S UNION SOLDIERS: THE COLORED TROOPS, THE LOUDOUN RANGERS, AND THE POTOMAC HOME BRIGADE

William E. Wilkin

Evidence exists to support the participation of Loudoun residents in the Union Army and Navy during the American Civil War. The three major groups include African Americans, the Loudoun Rangers, and the Potomac Home Brigade.

First, research by Kevin D. Grigsby indicates 248 African Americans born in Loudoun County served in the Union Army and 11 served in the Union Navy. [From Loudoun to Glory: The Role of African-Americans from Loudoun County in the Civil War, (2012).] Proof of linkage to Loudoun County may be drawn from three sources. First, the military record of the individual may state his place of birth, as may pension documents or widow’s claims. Second, the Clerk of Court of Loudoun County maintained an official document, the Register of Free Negroes. If an individual soldier or sailor had been listed in the Register before the war, his link to Loudoun is clear. [Register of Free Negroes: 1844-1861; also Abstracts of Loudoun Virginia: Register of Free Negroes 1844-1861, edited by Patricia B. Duncan] Third, several Union veterans are buried in Loudoun County with gravestones issued by the War Department. The process of awarding that honor was in itself an administrative finding of honorable service.

Second, research by Taylor Chamberlin and John Souders established that Loudoun County men served in the Loudoun Rangers, a unit of the Union Army. [Between Reb and Yank, Waterford Foundation (2011)] Lee Stone compiled a roster of 249 members of the unit showing place of birth. [The Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers: The Roster of Virginia’s Only Union Cavalry Unit, Waterford Foundation (2016)]

Third, research by Travis Shaw, librarian at the Thomas Balch Library, has identified 42 men from Loudoun County who served in the Union Army’s Potomac Home Brigade. [Archives at Thomas Balch Library]

As background, African Americans were not allowed to join the Union Army until the effective date of the Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863. Several states formed regiments of African Americans such as the famous 54th and 55th Massachusetts. The national government formed other regiments which were known as United States Colored Troops (USCT). Loudoun men served in both state regiments and the USCT. There was no one unit for Loudoun African Americans; the Loudoun men served in various regiments with different roles in the war. If listed together, Loudoun men were in campaigns and battles from the Carolina coast to the Mississippi valley, from Florida to the taking of Richmond.

The years leading up to the War were marked by the sale and forced migration of thousands of enslaved men, women and children from Virginia to enslavers in the Deep South. The enslaved, largely American-born, were torn from their places of birth, shattering lives and families at great profit to their sellers. This mass-migration has been coined “The Second Middle Passage” by author Ira Berlin, underscoring the sheer numbers of people affected and the resulting devastation to individuals, families and communities. Thus, it is not surprising that the service records of these Union African American veterans attest to enlistment far from Loudoun. Some veterans did return to Loudoun County and actively contributed to the new communities of freedmen.

The Loudoun Rangers were a unit formed by Union sympathizers who resided in Loudoun County. The unit was authorized by the War Department on June 8, 1862. Their commanding officer was Captain Samuel C. Means, a resident of Waterford. Though the county was evacuated by Confederate forces in February 1862, the Army of Northern Virginia operated in the county during the Maryland campaign of 1862, the Gettysburg campaign of 1863 and Early’s campaign of 1864. Means’ Loudoun Rangers were also confronted by the commands of John S. Mosby and Elijah White, which operated in the area with considerable local support. Their service is a long list of hard fights and ambushes on both sides of the Potomac. The Loudoun Rangers had a notorious fight in Waterford on August 27, 1862 at the Baptist Church losing against Elijah White’s cavalry. The Loudoun Rangers were based several times at Point-of-Rocks. Most valuable as scouts, the Loudoun Rangers also fought at Monocacy. Many left Loudoun County after the war. They and their families gave up a great deal for their decision to stand with the Union.

The Potomac Home Brigade was a predominantly Maryland unit formed to guard the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in late 1861. Some Loudoun Union men who had fled the county due to threats from their pro-Confederate neighbors enlisted in the Potomac Home Brigade. The unit was trapped at Harpers Ferry during the Maryland campaign and was exchanged. The unit fought at Culp’s Hill during the battle of Gettysburg. They also fought at Monocacy on July 9, 1864. Like the Loudoun Rangers, the elements of the Potomac Home Brigade (especially Cole’s Cavalry) had hard fights against Mosby, White and other Confederate units. Some members of the Potomac Home Brigade did return to the county after the war.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

NOTE: The Loudoun County Heritage Commission consists of 16 members. Bronwen Souders of Waterford is the Catoctin District Representative, and Edward Spannaus of Lovettsville serves as a Commissioner At-Large.