By: Claudette Lewis Bard

When I began studying my family history, I started looking at census records in order to get facts and statistical data. Some of the information gathered from the U.S. Census indicates where an ancestor lived, their age, gender and race. The census can often paint a picture of one’s life at a certain point in time in that it will often reveal one’s occupation, their family structure and whether they were literate. There are heartbreaking stories built into a particular year’s census records such as how many children a woman gave birth to, and how many were living. If the number of children born was more than the number living, that could indicate she lost a child or children.

But I believe most family historians would agree, the most valuable and captivating stories about ancestors are oral accounts. At that point, a family historian must then separate fact from folklore in order to get to a true narrative. Whether a story is folklore or truth, often times an ancestor’s love and kindness are brought out through these stories. This is the case when I learned about my great, great aunt, Grace Anderson Smith. Throughout this narrative, I will refer to her fondly as Aunt Grace.

The Early Years

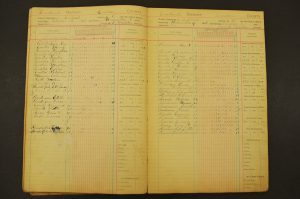

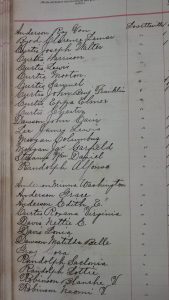

Aunt Grace was born Grace Anderson about 1890 in Lovettsville, Virginia, and was the seventh child of George Washington and Sarah Jane Anderson. She was related to me in that she and my great grandmother, Minnie Anderson Waters, were sisters. She was educated in Loudoun County’s segregated school system where, in 1896, she was a seven-year-old student at the Lovettsville Colored School which, in the late 1800s, was located at South Loudoun and South Locust Streets in Lovettsville. The building is still there, but it is now a private residence and the owners have made additions to the structure. The school was a one-room schoolhouse that housed several grades of students. She attended school with several of her brothers and sisters. In 1898, she continued her education at the same school along with her sisters Minnie and Edith, and her brother Ray.1

I was not able to locate Aunt Grace in Lovettsville in the 1900 U.S. Census. Her mother had died in 1892 at the young age of 33, and Aunt Grace was not living with her widowed father and her other siblings. She may have been living with other family members, if the family had been broken up due to the death of her mother. Aunt Grace was then ten years old.

George Washington Smith was born February 27, 1889, in Leesburg, Virginia, to Bob and Margaret Smith.2 By 1900, he was listed as a servant in Leesburg in the household of James Hall and his family. They were white. He was twelve years old. He could neither read nor write, and even though of school age, did not attend school. For reasons unknown, George made his way to Lovettsville by 1910, and was a hired hand in the F. William McKimmey household.3

While living in Lovettsville, he met Aunt Grace. It is often said that women marry men who share their father’s values, personality and traits. Perhaps George was like Aunt Grace’s father in those ways, but he most certainly shared his first and middle names–George Washington. On June 23, 1917, they were married in Leesburg.4

Throughout my research, I heard many accounts of the kindness and love that Aunt Grace bestowed upon those around her. This love and kindheartedness were evident when they adopted a child, a son named Richard. He was one month old in 1920. The details of the adoption were unclear but the affection was not. They lived in Lovettsville in close proximity to other family members including Grace’s brothers Etchison, Carl, Ray and their families.5 Both parents evidently knew what it was like to live away from their parents at an early age, and developed a certain degree of compassion for children who, for whatever reason, did not have parents who were able to raise and nurture them.

This compassion was, once again, evident when in 1923, they adopted a second child, a daughter. Phyllis was born in Freedmen’s Hospital (now Howard University Hospital) in Washington, D.C. They brought her to their home in Lovettsville. Aunt Grace and George set out to raise two children who were not naturally born to them. All that is known about Phyllis’s birth mother was that she was from Delaware and most likely single. From all accounts, Richard and Phyllis were not related.

The 1930s and 1940s

Sometime in the 1930s, Aunt Grace and her family moved from Lovettsville to the Curtis Wilson farm near Purcellville, Virginia. The census record in the 1940 U.S. Census was in the district known as Mt. Gilead. The Curtis Wilson farm was a dairy farm, and the family rented a tenant house and worked on the farm along with other families, both Black and white.

Work on the farm was hard work. Aunt Grace and her family all worked during slaughter season when pigs were slaughtered. There were also cows, fruit trees, and other animals on the farm as well. The tenant houses did not contain indoor plumbing, so the family used outhouses and drew water from a well. The conditions were not comfortable–to say the least–but the family continued to live there for several decades.

Family Reunions: The 1940s and Early 1950s

When Aunt Grace and her family lived in Lovettsville, they resided very close to some of her other siblings. Her sister Minnie and her family, by this time, had moved to Rockville, Maryland, where they settled into a home in which they owned; her brother, Etchison, had relocated his family to Washington, D.C. Lovettsville was over 10 miles away from the Purcellville farm and the work on the farm took up most of her family’s waking hours, so visits were limited. Aunt Grace, at some point, began hosting the Anderson-Curtis family reunions and the rented tenant house and adjacent farm land provided plenty of space to accommodate the large gathering. The reunion was so named the Anderson-Curtis family reunion because the attendees included the Andersons on Aunt Grace’s side, and the Curtis family who were related to Virginia Curtis Anderson, Etchison’s wife. The Anderson and Curtis families were very close when they all resided in Lovettsville.

And so, a tradition began that still exists until the present day.

Every summer, family members traveled to the Purcellville farm, by car, loaded down with food prepared in Rockville, Lovettsville, and Washington, D.C. kitchens. Families with children packed cars and traveled the roads to Purcellville. Once they arrived, they negotiated a long, rocky driveway into the farm to reach Aunt Grace’s tenant house. Aunt Grace had prepared food as well, something she was known for. Children had plenty of space to run and the adults caught up on events that happened in their lives. New babies of the family were introduced. Phyllis and her brother Richard never felt like an outsider to this loving family even though they were adopted. The family embraced them as if they were blood relatives. It turned out they did not know of their adoptions until much later in their lives, something that Aunt Grace kept from them and only revealed shortly before she died.

Aunt Grace’s sister, Orpha Anderson Redmond, and Orpha’s husband Dave Redmond, lived on a farm in Lovettsville. The Redmonds adopted a daughter named Martha, and they attended the reunion. As with Phyllis and Richard, Martha always felt that this was her family. Love and acceptance were part of the Anderson-Curtis family beliefs.

It is not certain in what year Aunt Grace began to host the family reunions, whether they began in the early or late part of the 1940s. She may have hosted them after her husband died which was 1946.6 At that point, their children Phyllis and Richard would have been teenagers. But for sure, it was a grand time for all who attended.

Phyllis graduated from high school in the 1940s and immediately moved to Washington, D.C. with her childhood friend and schoolmate, Aggie. Phyllis possessed a certain amount of independence in that she knew how to drive and had obtained her driver’s license. It is not known why she decided to leave. But she often talked about how hard farm work was and the blatant Jim Crow laws that plagued Virginia during the mid-part of the 20th century. She cited attending separate schools, and always spoke frankly about what life was like for Blacks in rural Virginia. She described life there as two separate societies. Blacks and whites did not mingle at all. There were separate facilities in every aspect of life, and African Americans “knew their place” in Virginia and did not dare to cross that line.

In contrast, the lifestyle of African Americans in the nation’s capital was much more appealing to this 18-year-old high school graduate. There were places like the Howard Theater that offered movies and brought national African American entertainers to its stage. A Black person was not relegated to seating in the balcony and could sit where they wanted to. Washington, D.C. offered culture and fewer restrictions as to where a Black American could go. There were employment opportunities greater than that of Virginia. A Black woman could be more than a domestic worker or farm hand, and that was perhaps what Phyllis sought.

Phyllis found a job in the mailroom at the U.S. Navy Department. She met and married Theodore Wells and settled in Washington to raise her family. She traveled quite often to Purcellville to visit her mother. By the 1950s, Aunt Grace had moved from the farm into Purcellville proper. She and Richard settled on G Street in a two-story house located in a Black neighborhood. Even though Purcellville was a small town back then, the house had quite a few amenities that the farm house was lacking. It had indoor plumbing, running water, and was so much more comfortable than the tenant house they had lived in for over 30 years.

Arthur Godfrey

In the late 1940s, Arthur Godfrey was a mainstay on CBS radio. Then on January 12, 1949, Arthur Godfrey made his television debut on a show on CBS Television entitled, “Arthur Godfrey and His Friends.” During the 1950s, he was seen not only on television but heard on the radio and at times, he was on the airways up to six days a week. I have heard him described as being as popular as Johnny Carson was back in the 1960s and 1970s. Arthur Godfrey was famous for playing his ukulele during his show as he sang along.7

By the mid-1950s, he had an estimated audience of 40 million listeners on his daily morning show. He had accumulated enough wealth to fly his own airplanes, own a huge duplex apartment in Manhattan, and run a very large estate in Virginia’s horse country.8 This large estate just west of Leesburg is now called Beacon Hill, incorporating over 1,100 acres. But at one time, it was home to Arthur Godfrey and it included “the big house,” which Godfrey and his wife called home.9

During the mid-1950s, Aunt Grace began to work at this sprawling estate. She was a cook in the big house and cooked huge meals for the Godfreys, their guests, and others who worked on the extensive farm. She wore to work a uniform that was identical to what was worn by the main characters in the movie, The Help, a film based on the novel by Kathryn Stockett.

Aunt Grace was sometimes driven to work by Phyllis, when her daughter visited her on the weekends, accompanied by her young son, Theodore, who had the nickname, “Tokey.” Arthur Godfrey welcomed Aunt Grace’s relatives with opened arms, and entertained Tokey when he sat on Godfrey’s lap. This scenario was repeated many times over the decade when Phyllis drove to Purcellville.

Aunt Grace had a warm and caring relationship with her first grandchild, Tokey. Their visits included good meals and plenty of delicious food. Grandmother and grandson had time together in that they often watched the television show, Perry Mason. Coincidentally, Tokey is now an attorney at one of the renowned law firms in New York City. But make no mistake, Aunt Grace was a strict disciplinarian where she did not take any disrespect from him, and made sure he did not get away with anything. Aunt Grace continued to show her love to the next generation.

The 1960s

One day in 1961, while Phyllis was visiting her mother, Aunt Grace fell ill. The ambulance was called and Phyllis accompanied her. For reasons unknown, Aunt Grace was transported to George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C., a hospital over 50 miles away. She died upon arrival to the hospital. The obituary read:

Grace Anderson Smith, 71, longtime Purcellville resident, a fine cook and good citizen, died Tuesday night. She was stricken suddenly ill and was dead on arrival at George Washington University Hospital, Washington.

She was the widow of George Smith. Grace and her husband lived for more than 30 years on the Curtis Wilson farm near Purcellville. After his death, she moved into Purcellville. She is survived by a son, Richard and a daughter, Phyllis.

Arrangements are pending at Hall’s funeral home, Purcellville.10

The visits to Virginia continued after Aunt Grace’s death, and Phyllis never missed a Memorial Day where she and Tokey traveled to Purcellville to visit Aunt Grace’s grave, and then stopped over to the old neighborhood to go and see neighbors.

Phyllis received the love of cooking from her mother, and her house in Washington, D.C. was the neighborhood house where all the kids gathered. Phyllis acquired from her mother the idea of equating food and love—they were one in the same. She was known as “Ma Wells” in her neighborhood and nurtured and nourished Tokey’s friends.

Aunt Grace knew the importance of family. Additionally, she and her husband knew how important it was to truly raise children, through discipline coupled with nourishment, nurturing and love. She made sure her family was brought together and, as a result, attendees of the present family reunions still reminisce about the old days. Descendants still gather each year for this celebration.

“As long as there is one person on Earth who remembers you, it isn’t over” ~Mandy Patinkin, actor and entertainer, from Finding Your Roots broadcast.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you, Theodore V. Wells, Esq. (Tokey), for taking the time to talk to me about your fond memories of your grandmother and mother.

Oral accounts were from my mother, Carolyn V. Lewis, and our cousin, Phyllis Smith Wells, cousins Ruth Ann Brown and Lorraine Howard. My mother shared countless stories of our family. Cousin Phyllis and I spoke many times at our family reunions.

Many thanks to Owen Curtis who shared with me several decades ago, stories about the Curtis family.

Endnotes:

- Lovettsville Historical Society and the Edwin Washington Project

- Loudoun County, Virginia death certificate, Ancestry.com

- U.S. Census, Ancestry.com

- Loudoun County, Virginia Register of Marriages, Ancestry.com

- U.S. Census, Ancestry.com

- Loudoun County, Va. Death Certificate, Ancestry.com

- CBS Sunday Morning broadcast aired Jan. 12, 2020, YouTube.com

- Obituary from the New York Times, March 17, 1983

- Beacon Hill Community Assoc. advertisement, beacon-hill.us

- Loudoun Times-Mirror newspaper, Aug. 21, 1961

The following link includes a story about Ray Anderson, Aunt Grace’s brother: