Hessian Soldiers in Lovettsville

By Edward Spannaus

During the American Revolution, tens of thousands of German soldiers were sent by their rulers to fight against the American colonists on behalf of the British crown. Thousands of them defected and stayed in America to build a better life. Some of them came to the German Settlement in Loudoun County, to the area now known as Lovettsville.

Among the dozen or more Hessian soldiers who settled here and raised families, are names familiar to us today, such as Abel, Arnold, Barnhouse, Dinges, and possibly Rickard.

There have been many stories over the years about Hessians and Loudoun County. There are stories about Hessians captured at the Battle of Saratoga being marched south through Loudoun, that some worked on local farms, and even that they were camped at Noland’s Ferry and built the brick warehouse there. Others have claimed, improbably, that Hessians were key in founding the “German Settlement.” Here, we will confine ourselves to what can be reasonably documented about those Hessian prisoners who actually settled here, a story that, to our knowledge, has never been told.

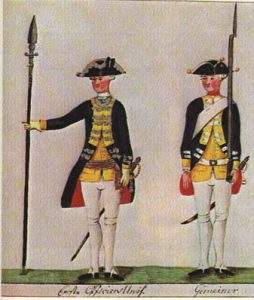

Who were the “Hessians”?

First, to clear one thing up: these Germans were not “mercenaries,” that is, soldiers-of-fortune who hired themselves out for money. They are better called “auxiliaries” or “subsidy troops,” since they were part of standing, regular armies in continental Europe whose existence was subsidized by the British monarchy in lieu of maintaining a large standing army at home.

As was the practice at the time, Britain, France, and other imperial powers made treaty arrangements with the rulers of a number of the states or principalities in central Europe, known at the time as the Holy Roman Empire (or, officially, the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation). As Voltaire famously quipped, the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. Nor, we could add, was Germany a nation at the time.

The majority of the German auxiliaries were from the principality of Hesse-Kassel, whose army was among the best-trained and largest in continental Europe. Of the almost 38,000 German troops who fought for the British in North America, about 26,000 were from Hesse-Kassel. Together with another 2,000 or so from Hesse-Hanau, it’s easy to see why all the German subsidy soldiers were lumped together as “Hessians.”

The rulers of the principalities which sent troops to North America under treaty arrangements with the British, were (listed in roughly north-to-south order in present-day Germany):

- Charles I, Duke of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel;

- Frederick Augustus, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst;

- Frederick, Prince of Waldeck;

- Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, King George III’s brother in law,

- William, Count of Hesse-Hanau, a nephew to George III; and

- Charles Alexander, Margrave of Anspach-Bayreuth.

We have found 14 German auxiliaries (“Hessians”) who either settled in the Lovettsville area or lived here at some point. Of course, this area wasn’t known as Lovettsville until decades later, but was known as “the German Settlement” in Loudoun County. Of these 14, 12 are pretty well confirmed (Arnold, the two Bornhaus cousins, Brand, Dinges, Ebel, Giese, Kirtzendorfer, Richter, Riebesam, Seyfert, and Schmidt; two (Hartmann and Rickard) are unconfirmed but likely; and then a 15th (Slates) seems unlikely. The full list, with brief biographical sketches, is below.

Almost all of our known “Lovettsville Hessians” were from two Hesse-Kassel regiments, and two Ansbach-Beyreuth regiments), which were taken prisoner at the surrender of British and German troops at Yorktown in October 1781, and were eventually taken to the “Hessian Barracks” in Frederick, Maryland. Another was from Hesse-Hanau, and was made prisoner much earlier, in 1777, probably at Saratoga.

Here is the distribution of our “Lovettsville Hessians” by army and regiment:

HESSE-KASSEL, Erbprinz Regiment: Arnold, C. Bornhaus, J. Bornhaus, Ebel, Giese, and Riebesam; von Bose Regiment: Hartmann, Richter.

ANSBACH-BEYREUTH, Ansbach Regiment: Schmidt, Rückert; Beyreuth Regiment: Seyfert, Kirtzendorfer; Jäger: Brand.

HESSE-HANAU, Gall/Erbprinz Regiment: Dönges.

Prisoners of War

1700 German troops were among the 7000 or so troops under Cornwallis’s command who were made captive with the British surrender at Yorktown, Va. in October 1781. The Germans were largely comprised of four regiments: Erbprinz and von Bose of Hesse-Kassel, and the two Ansbach-Beyreuth infantry regiments, plus a smaller number of riflemen (Jäger).

The German POWs were marched to Winchester, arriving in early November, and then were sent to Frederick, Md. in January 1782 – although some say that the Hessians were sent earlier, followed by the Ansbachers. They replaced the British POWs who were sent on to Pennsylvania. It is estimated that some 1,500 German POWs were crowded into the “Hessian Barracks” in Frederick. They were released as prisoners in mid-May of 1783, when many “deserted,” or simply decided to stay in America. At that point, the British weren’t anxious to transport the German soldiers back to their homeland, and some of the German princes didn’t want them all back either, so they were not really deserters at this point, but “stay-behinds.”

One of our “Lovettsville Hessians,” Christoph Dönges/Dinges, was in the Hesse-Hanau Army, Erbprinz Regiment, and was captured in 1777, likely at Saratoga. He was born in 1750 in Mittelbuchen, Hanau, and joined the army at the end of 1767. In 1776, his regiment was deployed to Canada, according to German records; the records report that he was seen in captivity in 1779 and 1781 in Virginia, and in 1782 in Lancaster, Pa. and was sold as an indentured servant in October 1782. All that is known of his date of desertion is that it was prior to September 1783.

What we know about the movements of his regiment is that they were captured at Saratoga in October 1777. It is reported that 3,379 British soldiers and 2,382 German soldiers were surrendered by British General Burgoyne – which represented a major turning point in the Revolutionary War. The prisoners here held near Boston for a year while negotiations over their fate took place, and the Continental Congress sought to encourage desertions among the German POWs. A year later, this groups of prisoners, known as the “Convention Army,” was sent to Charlottesville, Va., in a long winter march which passed through Loudoun County at Noland’s Ferry. When Cornwallis invaded Virginia, it was deemed advisable to move the British and German prisoners further away, so they were sent to Winchester in February 1781, and then to Reading, Pa. in June. By 1782, the “Convention Army” was pretty much broken up and dispersed to various locations, including Maryland. We assume that this is where Christoph Dönges deserted to remain in America with so many of his comrades.

Defections and Desertions

Not all the “Hessians” who deserted or defected were prisoners, but prisoners were the most likely, since they were exposed to German-Americans in Pennsylvania and western Maryland. It was a deliberate policy of George Washington and the Continental Congress to send the German prisoners to German areas in the colonies so that they would see how German immigrants lived here, and would therefore be more likely to defect, and in some cases, would even change sides and fight with the Continental Army.

Thus, after the “Convention Army” was marched to Charlottesville, Va., we find the German prisoners in our story being sent to Winchester, Va., Frederick, Md., and Lancaster, Pa. Often they were allowed to go out to work with local German farmers or tradesman, and thus get more exposure to German-Americans. Even those on the march from Virginia to the Frederick Barracks noticed the difference in the German areas, as one historian has reported: “On the march through Maryland, the German settlers showed them much kindness, and German speech and friendly hospitality gave them much comfort. Their food, too, improved, and their quarters were two barracks, with 100 huts . . . nearly all the farmers around were Germans—Swabians” (“Swabian being a term used for those from around present-day southwest Germany).

By most accounts, the Americans overestimated the willingness of the “Hessians” to desert. It was assumed that they had been sent here to fight against their will, and would resent their leaders and rulers, and be eager to start a new life here. It wasn’t that simple: most had loyalty to their units, If not to their ruling princes, and many had wives and children back home. (The average age of the German auxiliaries was about 24.) Desertion was much more common in the 18th and 19th centuries than today – especially among undisciplined troops — both in Europe and America; even during the U.S. Civil War, soldiers would wander off and go home for a while, and then return to their units. It was much harder to do this when your unit was fighting thousands of miles and across the ocean from your homeland.

Most of the German auxiliaries did return home, often welcomed with parades and celebrations. But a sizeable number stayed behind. This became easier to do after the summer of 1782, when American officials allowed German prisoners to earn their freedom and become American citizens in one of three ways: 1) join the Continental Army, 2) buy their freedom by money earned working locally, or 3) become indentured servants for a period of time. And, as we have noted, at the end of the war, both British and German authorities allowed some soldiers to stay behind, so as to avoid the costs of shipping them back to Europe.

For Hesse-Kassel regiments, the rate of desertions is estimated by historians at about 11%. When adding in those who stayed behind at the end of the war, the number rises to about 15-16%. For the Ansbach-Beyreuth troops, the number of deserted and missing is calculated at around 20%, and including those who were discharged, those remaining in American constituted about 30%.

Most of those who stayed behind in the German-speaking states in America, quickly made new lives for themselves. Some had already formed relationships with local women while working on farms or in the towns while still prisoners; church records in Frederick also show some POWs attending services and communing. As we see in the listing below, most marriages took place in 1783-85, and the former German soldiers quickly settled in and began raising families, with many going on to become prosperous members of their communities.

It seems that, even though they had come here on the British side, that there was little or no hostility toward them. As an example, Christoph Bornhaus married Rosina Roller. Rosina had two brothers, Conrad and John, who both fought with the Continental Army. Another sister, Catharina Roller, married Hessian defector George Ebel in January 1785. Conrad Roller himself was married to Elizabeth Slates, the daughter of another reputed Hessian, Friedrich Schloetz, and still another sister, Margareta, married Elisabeth’s brother, Frederick Slates, Jr. They all seemed to have gotten along quite well, these Continents and “Hessians,” appearing frequently as sponsors in each others’ childrens’ baptisms

Following is our listing of the known “Hessians” who settled in the Lovettsville area. There are likely others – and if you know of some others, or know more about those listed here, please let us know.

Lovettsville Hessians

Justus Arnold: Pvt., Hesse-Kassell, Erbprinz Regt., deserted by May 1783. In the Evangelical Lutheran Church (Frederick) marriage register,* for Oct. 6, 1783, is listed “Justus Arnold & Catharina Barbara Eberle both in Loudon County. Procl. there three times. Witnesses: Steinbrenner and many Hessians.” Justus/Jost Arnold and his family are listed many times in the register of NJLC. He was a sponsor at the baptism of a child of Christoph Bornhaus of the same Erbprinz Regt, and Adam Riebsamen of the same regiment was a witness at one of Arnold’s children’s baptism. It is not known when he died, but when Sarah Arnold was buried in 1894, she was described in the Lutheran church register as a daughter of “the late Justus Arnold.”

Johann Christoph Bornhaus: from Datterode, Pvt., Hesse-Kassell, Erbprinz Regt., deserted by May 1783. Married Rosina Roller on Aug. 11, 1784 at New Jerusalem Lutheran Church in Lovettsville. Witness to wedding of George Ebel, and to baptism of Ebel’s son. Christoff and Rosina later moved to Jefferson County, Ohio.

Jakob Bornhaus was a cousin of Christoph, also from Datterode; Pvt., Hesse-Kassell; served in the Erbprinz Regt., and had deserted by May 1783. Jacob and his wife Elisabeth both died in 1802 and are buried in the New Jerusalem Lutheran cemetery, as are a number of their children who died young or in infancy. Their graves today are unmarked. Three of their children were baptized at the German Reformed Church (now St. James in Lovettsville) between 1793 and 1798.

Georg Nicolaus Brand: Jäger, Ansbach-Beyreuth, Jäger Regt, Co. VI (von Waldenfels). Deserted 10 May 1783. Married Rosina Biegel 28 April 1784 at New Jerusalem Lutheran Church (recorded in Frederick ELC register); four children baptized at New Jerusalem.

Christoph Dönges/Dinges: Musketeer, Hesse-Hanau Erbprinz Regt., deserted before Sept. 1783. Married Catharina at New Jerusalem Lutheran Church; three children baptized there.

Georg Ebel/Abel: Pvt., from Datterode in Hesse-Kassell, Erbprinz Regiment Maj. Waldenberg Co.; deserted Oct. 1781. Married Catharina Roller on Jan. 3, 1785 at New Jerusalem Lutheran Church, as recorded in the ELC register. Sponsored baptism of a son of Christoph Bornhaus of the same regiment in 1785. Buried in Old Ebel Cemetery near St. Paul’s church in Between-the-Hills.

Heinrich Giese: Cpl., Hesse-Kassel, Erbrprinz Regt., Maj. Waldenberg Co.; reportedly captured at Trenton; deserted by May 1783; married Anna Maria Baker in Frederick in Sept. 1783. Served as pastor of German Reformed Church (St. James), Lovettsville, from about 1783 to 1794; then moved to Berlin, Somerset County, Pa. There is a story that a parishioner in Somerset County recognized Giese as a Hessian captured at Trenton, and walked out of the church.

Johannes Körzdörfer/Kirtzendoefer/Cartzendafner: Pvt., Ansbach-Beyreuth, Beyreuth Regt., Co. III (Lt. von Eyb Co.); deserted 13 May 1783; married Maria Reichardt 22 Nov. 1785 at Frederick ELC; some children born in Loudoun Co, Va.; son Johannes married Sophia Crabel at New Jerusalem, 13 Feb. 1817.

Henry Richter: Pvt., Hesse-Kassel, von Bose Regt., Col. Von Munchhausen Co.; deserted by May 1783; married and children baptized at Frederick Reformed Church; his will probated in Frederick County, listed him as “Henry Richter of Loudoun Co., Va.”

Adam Riebesam: Pvt., Hesse-Kassel, Erbprinz Regt., Maj. Waldenberg Co.; deserted by May 1783. Married Dorothea Steinbrenner 12 Nov. 1783 in Loudoun Co., as recorded in Frederick ELC register. Sponsor for baptism of child of Justus Arnold (same regiment) at New Jerusalem; two of Adam’s children baptized at New Jerusalem, and four at the German Reformed Church (where Henry Giese was the pastor).

Johann Adam Seyfert: Pvt., Grenadier; Ansbach-Beyreuth; Beyreuth Regt. , Co. IV (Capt. Von Quesnoy); deserted by May 1782. 5 children of Adam and Susanna Seyfert baptized at New Jerusalem Lutheran Church.

Lorenzo Frederick Schmidt (Smith): Pvt.; Ansbach-Bayreuth, Ansbach Regt., Co. III; Regt. Surrendered at Yorktown in October 1781; he deserted 9 Sept. 1783. Settled at Lovettsville and married Christine Agatha Sunifrank in 1790; affiliated with New Jerusalem Lutheran Church; died in Rockingham Co., Va. In 1820. (Former Va. State Delegate Joe May is a descendant.)

UNCONFIRMED:

Heinrich Hartmann: Hesse-Kassell, von Bose Regt., Lt. Col. duBuy Co. Deserted 1781. There was a Heinrich Hartmann with wife Elisabeth who had son baptized in 1786 at the Reformed Church (now St. James), but we have no proof that these are the same person.

Johann Simon Rückert/Rickard: Pvt., Grenadier; Ansbach-Beyreuth, Ansbach Regt., Co. II (von Seitz); deserted 15 October 1781. Married Susanna Meyer. 3 children baptized at New Jerusalem. Simon was sponsor for baptism of Susannah Abel (daughter of Hesse-Kassel soldier George Ebel). Simon Rickert buried 11 Feb. 1793 at New Jerusalem, at 40 years of age. Occupation: tailor. Note: A Rickard family history says that Simon was born in Loudoun Co. and “served for Virginia in the Revolutionary War, but this has not been confirmed.” In fact, there seems to be no record of him until the baptism of his son Peter at New Jerusalem in 1785, making it possible that he could have been a German auxiliary.

Friedrich Schlötz/Slates: Slates family lore states that Friedrich Slates, (1760-1830), or his father, was a Hessian soldier, and the new (c. 1940) family grave marker states that he was “A  Hessian soldier,” but we have not found any proof of this, and he is not named on any list of Hessian soldiers we have seen (but the records are admittedly incomplete). His father Friedrich Schlötz was reportedly born in Hesse-Kassel (making him a “Hessian,”) and son Friedrich was reportedly born in Frederick County, Md. In 1760 – seeming to make it impossible for him to have come to America with the Hesse-Kassel troops in 1776. The family came to Loudoun County around 1776, and was deeded land by Ferdinando Fairfax in 1800, to what was variously called the Slates Farm, “The Snow Place,” the “Dower Farm, and later the Edgar Williams farm.

Hessian soldier,” but we have not found any proof of this, and he is not named on any list of Hessian soldiers we have seen (but the records are admittedly incomplete). His father Friedrich Schlötz was reportedly born in Hesse-Kassel (making him a “Hessian,”) and son Friedrich was reportedly born in Frederick County, Md. In 1760 – seeming to make it impossible for him to have come to America with the Hesse-Kassel troops in 1776. The family came to Loudoun County around 1776, and was deeded land by Ferdinando Fairfax in 1800, to what was variously called the Slates Farm, “The Snow Place,” the “Dower Farm, and later the Edgar Williams farm.

- Note: The Lutheran Church in Lovettsville was served by ministers from Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick during this time, and up until around 1784, marriages and other pastoral acts were listed in the Frederick church register; the Lovettsville Lutheran Church (now New Jerusalem didn’t begin keeping its own register until 1784-85. So if a Frederick church record says “in Loudoun County,” it is presumed that the marriage took place in Loudoun in the German Settlement.

Resources:

Although I have been aware of some of the Lovettsville Hessians for years, I learned of many more when reviewing the research files compiled for the uncompleted Hessian Descendants Project of the Sgt. Lawrence Everhart Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution, Frederick, Md. The SAR project used as its database the compilation of prisoners in the Frederick Barracks who stayed in this area, by descendant Nancy Rice Kiddoo entitled “Of Revolutionary Memory,” published in Der Reggeboge, the Journal of the Pennsylvania German Society, Vol 23, No. 2 (1898). Another article in that issue, “Prisoners of War in Frederick County, Maryland, During the American Revolution,” by Lion G. Miles, was also helpful. I also followed up Kiddoo’s impressive work with my own research in Lutheran church records in Frederick and Reformed and Lutheran records in Lovettsville. Other sources used are:

Daniel Krebs, A Generous and Merciful Enemy: Life for German Prisoners of War during the American Revolution, University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

Edward J. Lowell, The Hessians and the other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War, Williamstown, Mass., Corner House Publishers, 1975.

Hessische Truppen im Amerikanischen Unabhängigkeitskrieg (HETRINA), Marburg, Germany: Archivschule. Although not easy to use, this comprehensive database of Hessian soldiers in America can be usefully consulted by someone who is not fluent in German.

This website “AmRev Hessian” has many useful links and lists: http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~amrevhessians/military/names.htm