By Doria R. Owen

The shoe box marked “Letters” had been silently waiting atop a stack of forgotten boxes for over ten years. Once opened, the story they tell is much older than that. The shoe box contains correspondence between Dr. John James Henshaw and concerned citizens, patients, and friends during the Civil War and its aftermath.

One of those close friends became my husband’s second great-grandmother. Dr. Henshaw lived during a time when his town, his state, and his country were bitterly divided. In letters addressed to “My Friend,” he laments the multitude of lives sacrificed at Gettysburg, and he mourns the recent death of President Abraham Lincoln.

Many of the tattered envelopes were addressed to “Dr. J.J. Henshaw, Lovettsville” — a town I was not familiar with. That is where my Internet search began. During my search I encountered the Lovettsville Historical Society’s article published in March 2020 entitled “Lovettsville Doctors Over the Years,” which mentioned Dr. Henshaw. This led to my e-mail conversations with Ed Spannaus. My husband and I arranged to meet him at the Lovettsville Museum on November 4.

During our meeting we were also joined by Mike Zapf, the Museum Director. These gentlemen were a wealth of historical knowledge. They recognized several of the names in the century-old letters, like Samuel L. Steer and W. H. Fletcher. Ed and Mike revealed details they knew of these men’s lives. There was even a portrait of one of the letter writers, Thomas J. Cost, hanging on the museum wall. It was thrilling to be in the town Dr. Henshaw once called home, and to connect the lives of those writing to him. Along with the letters, archived newspaper clippings, and various other sources, I have compiled a timeline of Dr. Henshaw’s life.

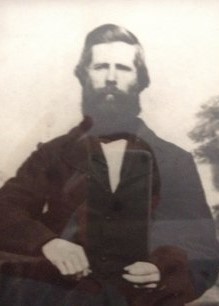

Dr. John James Henshaw began his life in Frederick County, Virginia as

John James Gardner. He was the second born to David Hancher, a farmer, and Elizabeth Gardner. John James was born on January 3, 1812. He may have been named after John, David’s father and James, his uncle. Mary Alice Wertz, a direct descendent of David Hancher, as well as a genealogist and author, states in her book The Henshaw Collection that David and Elizabeth never married. She uses death certificates as proof.

In the summer of 1824, David Hancher named his sons Barton Gardner and John James Gardner in his will. He bequeathed to each of the boys two hundred dollars, to be used towards education until they acquire a trade. Then, at the age of twenty-one, they were to receive the remaining amount. The will is recorded in the Frederick County, Virginia, Courthouse. John James was eleven years old when his father died. When Elizabeth filed suit against David’s estate, she signed with a mark. The children identified themselves as “Henshaw” following the distribution of their inheritance from their father’s will.

According to an obituary of Dr. John J. Henshaw published in February 1894, he farmed in Maryland from 1868 till 1872. This was after he fled from Loudoun County with his wife and son. The obituary also states that he was a millwright and a thresher builder in his early years. I have not found evidence of him in those trades.

Early years

J.J. Henshaw attended medical lectures In Philadelphia in 1840. Medical training in those days was for about two years. He received his license to practice medicine in Loudoun County, Virginia in 1857. According to his obituary, he practiced dentistry, medicine, and surgery for 28 years primarily in Loudoun County. It is said that during the Civil War, he was the only doctor remaining in Lovettsville. He was one of the two physicians to treat Capt. Luther W. Slater of the Loudoun Rangers, after Slater was seriously wounded at the fight at the Baptist Church in Waterford on August 27, 1862. Under the physicians’ skilled care Slater’s arm was saved from amputation and he eventually regained his health and most of his strength.

Dr. Henshaw had been part of the political process at least since 1856 when, according to an article in the Shepherds Town Register in September 1856, “Dr. Henshaw calls a meeting to order of an enthusiastic [Millard] Fillmore crowd in Morrisonville, Loudoun Co.” The Leesburg, VA Democratic Mirror, Nov. 14, 1860, reported that Adjutant J.J. Henshaw attended a military parade in Frederick, MD. This was likely in his capacity as an aide to Col. William Giddings of the 56th Regiment of Virginia Militia.[i]

In November, 1863, Unionist Loudoun County citizens elected Henshaw to represent them in the House of Delegates of the Restored Government of Virginia, which was organized by Unionists and which met in Alexandria.[ii] In January 1864, Henshaw was appointed as Treasurer of the Unionist Government. And in a rump election held only in Unionist north Loudoun, Henshaw and two others were elected as delegates to a Constitutional Convention being organized by the Restored Government, which was held in Alexandria from February through April 1864.[iii]

During that same winter of 1864, an unnamed friend shared his views and gave sound advice to Henshaw. “I sincerely hope the institution of slavery may be a doomed one, may it never have a resurrection in this part of the state. You say you feel that you have no qualifications for law-making. Well, just remember patient perseverance always surmounts great obstacles.”

After the war

After the war, in 1866, Henshaw gave sworn, confidential testimony before the Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction. He said, describing the mind-set of the ex-confederates who were back in power in Virginia: “I do not think they consider that their State rights or anything of that sort has been impugned. They have been overpowered, but they were right nevertheless. What they claimed and what they struck for they were entitled to, and are entitled to yet.”

Henshaw accused the federal government of not giving full assistance to the Freedman’s Bureau and the freed people. He testified about the unfair trials of loyalists versus those of ex-confederates, and the existence of false rumors that were instilling fear in citizens.

Following his testimony, which obviously had not remained confidential, Dr.

Henshaw felt ostracized by his ex-confederate neighbors. The Virginia Free

Press of May 24, 1866, reported the burning of Dr. Henshaw’s barn and stable in Loudoun County, and the loss of a valuable horse. He was not the only one with those feelings. There were others that felt their government had betrayed them. They too felt unsafe and threatened.

Post-war life in Maryland

In order to protect his wife and young son, Dr. Henshaw decided to leave his medical practice in Lovettsville and return to Frederick County MD (where he had lived in exile during much of the war). Along with Dr. Henshaw and family camea young freedman, Amos Lucas. Since 1867, Amos had been performing office chores for Dr. Henshaw. In the Maryland census of 1870 and 1880, Amos is listed in the Henshaw household.

Henshaw’s relocation to Frederick County in 1868 was a logical choice. His wife Margaret Rouzer, whom he married in May 1866 was born in Mechanicstown (now Thurmont). She had large family waiting to welcome and encourage them.

Dr. Henshaw did not practice medicine in Thurmont until the death of Dr. William White of that town. In the Catoctin Clarion of Mechanicstown for February 26, 1885, there is a professional advertisement stating Henshaw’s determination to return to the practice of medicine. Before that, he engaged in farming and in the sale of Carlisle shoes and boots. The Catoctin Clarion in Nov. 1875 declared “Dr. J. J. Henshaw, who on account of his Union sentiments during the late war, was threatened to be hung. He still lives however, and sells Carlisle boots and shoes with great rapidity.” In the summer of 1890, Henshaw also partnered with a Mr. Zimmerman in a promising livery business, as reported in the Catoctin Clarion newspaper on June 26, 1890.

Threats and the malicious destruction of his property in Loudon County did not stop the resolute Dr. Henshaw. He continued being active in politics and his new community. June 1876, Dr. Henshaw was elected to the Board of Directors for the Male and Female Seminary in Mechanicstown.

The Independence Day celebrations in Thurmont in July 1876 – the nation’s Centennial — were organized by Dr. Henshaw. The Catoctin Clarion reported: “The Chief Marshall Dr. J.J. Henshaw, and aides, mounted on fiery chargers with sashes and rosettes, then made their appearance and commenced forming the procession, which was no easy task as the crowd was so large and at times ungovernable. But the doctor was equal to the emergency, and with a great degree of coolness and past experience soon had the procession formed and ready to move.”

In November of 1883 he was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, representing Frederick County. And in March of 1889, Henshaw was appointed Postmaster for Mechanicstown — a position he held for four years.

Dr. John James Henshaw’s significant life ended on February 1, 1894 in Thurmont. He was 82 years old. He is buried in the Weller’s Cemetery, in Thurmont, along side his wife, Margaret and five children — a family he continually provided for in a variety of ways.

Dr. Henshaw was a man who, despite the challenges and controversies of the times, served his community and his country well.

* * * * *

Doria and Britt Owen are generously lending the Henshaw letters to the Lovettsville Historical Society for scanning and transcription. As the transcriptions are completed, we expect to be publishing a number of the letters, or excerpts from them, in this newsletter. –Editor.

NOTES:

[i] The 56th Militia Regiment, split apart with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, with some members and whole companies siding with the Union, and others with the secessionists.

[ii] Henshaw’s first foray into electoral politics appears to have been in May 1861, when he stood as a Inionist candidate for one of Loudoun County’s two representatives to the Virginia House of Delegates. This race was part of the same election in which the referendum on secession took place. Henshaw and his fellow Unionist candidate William F. Mercer won in northern Loudoun – where secession was voted down – but lost in the county overall, where the ordinance of secession carried the day. See Taylor Chamberlin and John Souders, Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia (2011), pp. 37-40. –editor.

[iii] The primary goal of the Constitutional Convention, one that was supported by President Lincoln, ws the abolition of slavery. Although the “Pierpont Constitution,” named for Governor Francis Pierpont, was only in effect in the handful of Union-controlled counties during the war, it had far-reaching effects after war when it was in force throughout Virginia until the adoption of the Reconstruction “Underwood Constitution” in 1869. The Pierpont Constitution abolished slavery, established free public education, and reformed the tax system and the judiciary, among other things. Between Reb and Yank, pp. 240-241. –editor.