By Nancy Spannaus

In the Hamilton-vs.-Jefferson conflict that raged throughout America in the early Republic, there weren’t many parts of Virginia which consistently elected opponents of Thomas Jefferson, but one of them was Loudoun County. From the Constitutional ratification convention on into the late 1830s, Western Virginia, including Loudoun, served as a stronghold[1] of the Federalist Party of George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, and consistently elected proponents of the Federalist program of internal improvements to both Richmond and Washington. Loudoun County was considered the strongest Federalist center in the state.

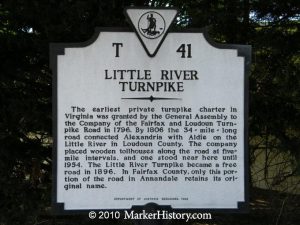

While the names of the successful Federalist politicians may not be well known today, their accomplishments are all around us. There’s the town of Middleburg and the Little River Turnpike, both founded by the man considered the founder of the Federalist Party[2] here, Leven Powell. There’s the town of Aldie, founded by Federalist Charles Fenton Mercer, as well as the remnant of his most renowned accomplishment, the C&O Canal. There’s Nolands Ferry, whose owner William Noland was a Federalist delegate in Richmond … the list could go on and on.

These men were elected to the Virginia House of Delegates and the U.S. Congress, despite the virtual lock-grip on the political process by the Jeffersonian party through the courthouse system. To do that, they had to win the support of their fellow citizens, most of whom were small farmers. While the lists of those citizens are not currently available,[3] I will focus in this report on the two most prominent leaders, Powell and Mercer.

Who were the Federalists?

The grouping called the Federalists was born in the fight for the ratification of the Constitution. Advocates of the new Federal government had chosen that name for themselves, thus dubbing the opposition the “anti-Federalists.” The undisputed leader in the fight for the Constitution was Alexander Hamilton, who played a crucial role in its framing.

To Hamilton, the Constitution’s governing framework was inextricably entwined with the ability to implement his nation-building economic program, later known as the American System of Economics. This was a program to build a thriving nation-state, in which the national government would ensure credit for essential businesses and infrastructure, back manufactures and scientific progress, and provide for the general welfare of the entire population. Hamilton elaborated his approach most fully in his Report on Manufactures, which was presented to Congress in 1791. That Report, and its ramifications for the later development of the United States, is the major focus of my book, Hamilton Versus Wall Street: The Core Principles of the American System.[4]

The Federalist Party, on the other hand, was comprised of a wide variety of social groupings, some of which were strongly opposed to Hamilton’s push for industrialization even as they supported a strong central government. Among these were merchant traders who were committed to making their fortunes through trade, rather than having the country invest in creating its own independent manufacturing base. There were also Southern planters who opposed what they saw as mobocracy, but remained wedded to the de facto feudal system of slavery (which Hamilton opposed). Thanks to these groups, the Federalist-dominated first Congress didn’t even bring the Report on Manufactures to a vote.

There never was a unified national party[5], especially after the departure of Washington and Hamilton from national office in 1796.

In Virginia, the Federalist Party promoted certain key features of the Hamiltonian program. Most prominent was the push for internal improvements: government-funded infrastructure, in the form of canals and turnpikes, on both the state and Federal levels. Thanks to the efforts of Federalists like Powell and Mercer, western Virginia, Loudoun included, gained a network of roads and canals which brought prosperity to a rapidly growing population. The Party also played a prominent role in fighting for expanding banks to service the West, increased suffrage for the less well-off, for free public education (for white citizens), and for restricting, if not abolishing, the slave trade and slavery itself.

Who were the Virginia Federalists?

Going into the crucial Virginia ratifying convention, which began on June 1, 1788, the Federalists could count on many eloquent supporters and an apparent majority, but their success was not by any means assured. Of particular concern were the western counties, including those in Kentucky, then part of Virginia. The opposition to the Constitution was led by Patrick Henry, who railed against having a strong central government. His view was in line with that of Thomas Jefferson, who was in France at the time, but expressed strong doubts about the framework..

Loudoun’s delegation to the convention was split, one for (Leven Powell) and one against (Stevens Mason).

Ultimately, the Western counties gave victory to the Federalists by 89 to 79. But as Hamilton and Washington proceeded to tackle the financial crisis of the republic by pressing for Hamilton’s American System (the Federal assumption of state debts, national taxation, and the establishment of a national bank), the fissures re-emerged stronger than ever. Soon after Jefferson’s return from France, Hamilton’s partner in writing the Federalist Papers, Virginian James Madison, switched from his nationalist outlook, to becoming Jefferson’s main ally in his campaign against Federal power and industrialization.

Simmering just below the surface of the debate – which publicly centered on Federal taxes on domestic liquor – was the issue of slavery. As Patrick Henry and others often said, if the Federal government could create a National Bank and expand its powers over the economy, then it might decide to manumit the slaves! Jefferson’s line of attack, which he waged heavily and often anonymously through his press, was that expanded Federal power amounted to monarchical power, and therefore must be resisted. Thus was born the myth that Hamilton was a monarchist.

Three issues – industrial development, interstate and international commerce, and slavery – tended to define the political dividing lines in the state. Joining with Jefferson were what was called the Tidewater elite, major plantation owners, as well as numbers of less wealthy farmers in the Piedmont and Southside. Federalists were clustered in some of the major cities such as Alexandria and Richmond (centers of commerce) and in the western counties, the Eastern Shore, and the Northern Neck. On the whole they were poorer, owned little land, had few or no slaves, and were historically less represented in the Virginia state government.[6] They also tended to be more inclined to curbing slavery.

Top on the minds of many Federalists was the issue of transportation. Loudoun County, for example, was a major wheat producer, having abandoned tobacco and adopted the Binns agricultural system that replenished the soil. But how were the farmers to get their produce to market? Unlike the cotton and tobacco producers of the Tidewater, they did not have natural navigable water transportation. Thus, they wanted Federal support for building canals, turnpikes, and roads in order to connect them to their markets. They also were anxious for access to credit for investing in their farms, a need which Hamilton’s national banking system addressed.

The Loudoun Elections

The Loudouners elected on the Federalist ticket were jurists, planters, businessmen, and land speculators. Some of those elected to the House of Delegates from Loudoun in the 1790s and 1800s were: William Butler Harrison; William Noland; Joseph Lewis, Jr.; Burr Powell (son of Levin); and Stephen C. Rozell (aka Roxzel). Loudoun’s Francis Peyton, a longtime member of the legislature prior to the Revolution, served as a state senator from Loudoun and Fauquier.

On the Congressional level, Loudoun was in a district with Fairfax and Prince William counties. The first Loudouner elected was Leven Powell (1799-1801). Loudoun’s Joseph Lewis, Jr. became the U.S. representative in 1803, a position he held until 1817. Then the victory went to Loudouner Charles F. Mercer, who was nominated by the General Committee of the Federalists (then run by Burr Powell), ran as a Federalist, and then switched parties once he was elected.

Many of these elections between 1803 and 1817 were hotly contested, and often the Democratic-Republican candidate won in Prince William and Fairfax. The margin of victory came from the strong vote in Loudoun for the Federalist candidate. The same pattern held true during Mercer’s 1817 to 1839 stint in Congress.

Mercer, who first served in Richmond for seven years, faced two very spirited challenges in his Congressional races. The first was in his first race where he was pitted against Democratic-Republican Armistead Mason, who presided over the Selma Plantation. The issues were fundamental: Mercer campaigned for national unity, internal improvements, and national reconciliation, whereas Mason adamantly opposed the federal government’s right to fund internal improvements. The two parties also clashed on the issue of the War of 1812, which the Federalists generally thought was unnecessary; however, Mercer, while criticizing the need to go to war, served honorably in defense of Virginia against the British invasion. Thus, he could win support from the Quakers in Loudoun, even while showing his patriotic credentials.[7]

The outcome was so close (72 votes) that Mason challenged it in Congress. He lost.

Mercer was also challenged in 1821 and 1823 from within his own party by Federalist Sydnor Bailey, who put himself forward as a simple farmer, in contrast to the well-educated lawyer Mercer. One of Bailey’s criticisms of Mercer was that he wasn’t a true friend of slave-holders, and was an enemy of the economy and a dangerous visionary. After Bailey was defeated in 1823, Mercer ran unopposed in 1825. In 1827 he bested Democratic-Republican opponent Robert Thompson by drawing a large margin of votes in Loudoun, which was also voting on a referendum for a state Constitutional convention. Loudouners were overwhelmingly in favor of such a convention to redress their lack of representation, a cause which Mercer, of course, dedicated himself to advancing.

Now, to the profiles of the two major Loudoun Federalist leaders of the period, Leven Powell and Mercer.

Leven Powell (1737-1810)

Leven Powell was born to a well-off family in Prince William County in 1737, and moved to Loudoun in 1763, following his marriage to a member of another prestigious family, the Harrisons. Here he built a career as “a soldier, politician, merchant, land speculator, agricultural innovator, and transportation developer.”[8]

Powell settled on 500 acres in the southern part of Loudoun county. There he farmed wheat, and eventually set up a mill and merchant store in 1771. His business thrived, and by 1787 he was known as one of the richest men in the county. He founded the town of Middleburg (part of his property) that year as well.

As the Revolutionary movement took hold in Virginia, Powell began to move to political prominence. He was elected a member of the County Committee of Safety in 1774, and was one of the convenors of the June 14 public meeting at the Loudoun County Court House which adopted a series of Resolutions in support of Boston (then under siege by British troops), including vowing non-importation of tea or other goods (including slaves) with Great Britain until the Tea Tax was repealed.

Powell also enlisted in the military. First, he was in the Minutemen, then Virginia’s Prince William Battalion, and eventually the Continental Army itself. George Washington himself designated Powell to become a Lieutenant Colonel in the Sixteenth Virginia Regiment in January 1777. Powell ended up at Valley Forge, where he became extremely ill; he was forced to resign his commission for health reasons in November of 1778.

The retired soldier served in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1779, and then returned to business, where he engaged in ventures for extending much needed transportation routes to Loudoun, as well as western land speculation. He became involved in George Washington’s Potomac Company, the enterprise Washington envisioned as a vital route to the Western lands, both for trade and political unity of the country. Powell bought stock and also served as a Director on several occasions—thus undoubtedly coming into contact with Washington and his political/economic views on developing the country. Of course, creation of more rapid, reliable transportation routes to the West would also aid Powell’s own merchant business, as well as Loudoun as a whole.

Powell’s involvement with the Continental Army and the Potomac Company undoubtedly contributed to his becoming an avid advocate for the adoption of the U.S. Constitution. (Federalists were more likely than Democratic-Republicans to have had distinguished military careers.) He understood the need for a strong federal government. He went on to win the highly contested election as one of two delegates from Loudoun to the 1788 Virginia Ratification Convention.

(Powell’s sentiments were also expressed in his layout of the town of Middleburg, notably the streets of Constitution, Jay, and Federal.)

Powell’s next political role was in the Virginia House of Delegates, where he engaged in the heated debates over the Hamilton-Washington program, notably Federal Assumption of state debt and the National Bank. Unlike the Jeffersonians, Powell saw a harmony of interests between agriculture and banks, writing later that “it is an advantage to the agricultural interests that the mercantile capital should be as large as possible.” This is a Hamiltonian idea.

The later 1790s saw Powell return to the political fray, after three years as a private citizen. In 1796, even while being forced to defend himself from charges of being a monarchist, he ran a winning campaign as a candidate for the Electoral College. He drew national attention with his attacks on Thomas Jefferson, then a candidate for President against John Adams, as having been a slacker in the War of Independence, and being involved (with Aaron Burr) in planning “rash and violent measures” for the last session of Congress. Ultimately, he was the only Virginia elector to cast his vote for Adams, and one of two in the entire South. For this, he also gained national notoriety.

The monarchist charge against Powell was likely discounted by many farmers and merchants in Loudoun because of its source—a planter aristocracy that rode roughshod over them in Richmond. These farmers and merchants looked to the Federal government to protect their interests from local oligarchs. They were particularly happy about the way the Potomac Canal was improving their ability to send goods to markets, and the consequent increase in the value of their land.

Powell’s next major political battle occurred in the uproar around the 1798-1799 Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, in which these two states declared their insistence that the Constitution was a compact among the states (not of “we the People), and that they considered it their prerogative to disregard the Alien and Sedition Acts as unconstitutional. These statements were read by Hamilton and others as declarations of defiance against the Constitutional order, in favor of states’ rights.

For his part, Powell wrote:

I cannot for my soul find out from where the opinion is taken up that the states are a part in the compact formed with the General Government. In vain have I looked into the Constitution to find it. As far as I am able to form an opinion on the subject, the people have formed both governments, that of the states for local purposes and other for national powers, and their representatives go into each with all the powers of the people to promote their interests and secure their rights peace and happiness … so far as respects their respective limits….

Coming off this controversy, Powell ran for Congress, winning election as part of a general Federalist wave in 1799. He got the personal support of General Washington, as well as the residents of the Shenandoah Valley and Loudoun. In an atmosphere heavily shaped by French rebuffs and threats against the United States, the Federalists won eight seats out of the 19-person Virginia Congressional delegation, a major advance. The Federalist bloc was not unified, however, on issues such as the standing army (which had been expanded in the face of the French threat) and the Alien and Sedition Act; Powell maintained a hard line in favor of both.

Powell refused to follow Hamilton’s admonition in the 1800 Presidential electoral stalemate between Burr and Jefferson, choosing to vote for Burr. He found himself increasingly out of step with his constituents and chose not to run for re-election in 1801. He returned to farming, running what he called an “experimental farm,” even while keeping up political policy discussions with his son Burr Powell, who was in the state legislature. He also continued to promote transportation infrastructure, such as a turnpike from Alexandria to western Loudoun. His health deteriorated to the point where he travelled to Bedford, Pennsylvania, to take advantage of the springs. There he died in 1810.

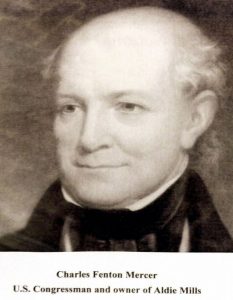

Charles Fenton Mercer (1778 to 1858)

Charles Fenton Mercer was the most prominent Federalist from Loudoun County, making a major impact on national as well as Virginia state politics. Yet I would call him a transitional figure, for as soon as he was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1817, he changed his party affiliation to align with his friend, Republican President Monroe.[9] Throughout the 1820s and ‘30s he was a strong ally of the American System program of President John Quincy Adams and the faction of the Democratic-Republican Party which became the Whigs (think Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln).

Mercer’s political hero was President Washington, whom he had the good fortune to know personally, thanks to the fact that his father collaborated with Washington as a member of the Continental Congress. This allegiance was reflected most in Mercer’s fight for government support for internal improvements, especially Washington’s incomplete Potomac project, but I believe it is also evident in his campaign for public education and against the slave trade.

Mercer embraced Washington’s firm belief, as expressed in his Farewell Address, that “It is substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government.”

Four issues consumed Charles Mercer during his political career: 1) public education; 2) internal improvements 3) stopping the slave trade; and 4) extending the franchise. He pursued these in both the Virginia State Legislature (1810-1816) and the U.S. Congress (1817-1839). Mercer resigned from the Congress one year after being re-elected in 1838.

In the rest of this paper, I will outline Mercer’s campaigns on these four issues. I will necessarily have to put aside a massive amount of material on other aspects of his life, including his education at Princeton, trips to Europe, founding of the town of Aldie (1804), participation in the War of 1812, and development projects in Texas in his later years. As you may gather, Mercer was almost always actively pursuing a project he considered important to public improvement for the nation.[10]

Public Education

Charles Fenton Mercer was an initiator of Virginia’s Literary Fund, a state agency founded in 1810 with the intent of having a dedicated income stream for education, and still in existence today. Mercer strongly believed in mass public education, as he expressed it in his 1826 Discourse on Popular Education:

Intellectual and moral worth constitute, in America, our only nobility and this high distinction is placed by the laws and should be brought in fact within the reach of every citizen. The equality on which our institutions are founded cannot be too intimately interwoven with the habits and thinking among our youth. (emph. added)

Once the Literary Fund was established in 1810, Mercer led the fight to expand and fund it; his efforts lasted until his final term in the Virginia General Assembly (1815-6). At that time, he proposed a comprehensive system of public education for the state, starting with establishing primary schools in each township, which would be free of charge and available to all white children. His emphasis contrasted with that of Thomas Jefferson, whose priority was the establishment of the University of Virginia, i.e., the education of the elite.

Mercer’s comprehensive plan failed to pass the legislature, due to opposition in the Virginia State Senate. Ultimately, Jefferson’s approach was adopted, with the chartering of the University of Virginia in 1819. Broad public education in Virginia had to wait until 1870!

Internal Improvements

Mercer was a tireless advocate for public improvements (what we would today call infrastructure) in both the Virginia House of Delegates and the U.S. Congress. In the state house, he pushed for the establishment of an Internal Improvement Fund, and ultimately succeeded in establishing and heading a Board of Public Works, which was oriented to funding badly needed transportation in the state. Mercer received enthusiastic support for his projects from his constituents, and other delegates from the western counties especially, who were anxious to have access to the rest of the state. Mercer’s proposals featured joint funding by the state (through profits from the Bank of Virginia) and private capital, the latter required to provide 60% of the funding.

Complementary to his direct push for canal and road projects was Mercer’s advocacy for expanding access to credit for enterprises in the states. He became head of the Banking committee in the Assembly and fought to establish new banks, particularly ones that would serve the western counties. He also participated in the vigorous debate over the re-charter of the Bank of the United States in 1811, coming down in favor.

When elected to Congress in 1817, Mercer escalated his fight for international improvements. He became chair of the House Committee on Roads and Canals (for 9 years) and advocated a national system of those means of transportation. But it was one particular project, George Washington’s signature project, which consumed his energies for the next 15 years: The Potomac Canal.[11]

Mercer campaigned tirelessly to get Federal and state (Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania) funding for completing a navigable waterway to the West. These included public meetings and conventions, Congressional speeches, and lobbying Presidents Monroe and John Quincy Adams. One of the meetings was a large public gathering in Leesburg on August 28, 1823 to promote the benefits of the Canal.

The Leesburg meeting established a movement to gain a national charter for the Canal company. It concluded with the following resolution.

WHEREAS, The improvement of the navigation of the River Potomac by a canal from the seat of government to the Great Cumberland Road to be thence extended, as soon as practicable, so as to meet a similar canal from the head of steam navigation to the nearest western water, is an object of inestimable importance, not only to the several states through whose territory the contemplated canal may pass, but to the commercial and political prosperity of the United States in general: Be it therefore recommended to the citizens of the several counties and corporations disposed to co-operate in the promotion of the above object, on order to devise some practical scheme for its certain and speedy accomplishment; to elect, respectively, two or more delegates to represent them in a general meeting to be held in the city of Washington, on Thursday, the sixth of November next.

The Washington convention did occur, keynoted by Mercer, who put forward detailed plans for the Canal’s construction, and for funding it. His concluding call went as follows:

Let us not despair of accomplishing a purpose so beneficent. Let us not stop till we have united, by indissoluble ties, the West with the East – fortified and embellish with the seat of their common government—drawn together the remote extremes of its widely extended territory, and infused new vigor and activity into all its operations, for the common defence, general welfare, and lasting happiness, of all its members.

Initial success was finally achieved with the passage of the C&O Canal bill by Congress in March of 1825, right before Monroe left office. In Mercer’s view, this accomplishment was a step toward fulfilling President Washington’s great dream.

That bill came as a result of President Monroe’s de facto endorsement in his last Message to Congress. Mercer followed up by introducing a bill for a Federal government subscription to the Canal company to the tune of $1 million. Thus, it would join the state legislatures of Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, all of whom ultimately passed legislation to fund the company, as well as private investors and cities.

Mercer’s vision, it must be added, went beyond the Canal itself. As he outlined in an April 25, 1826 speech to Congress, he wanted to see the creation of a corps of Topographical Civil Engineers to carry out a national geographical survey in the interest of guiding placement of public works, and another corps of Civil Engineers to estimate costs of the works proposed, and supervise construction. The major works he proposed were: 1) the C&O and Ohio/Erie canals; 2) improving navigation of the Tennessee, Ohio, and Connecticut rivers; 3) extending the Cumberland Road; and 4) constructing a military road from DC to New Orleans.

The process of bringing the C&O Canal company into being was long and taxing, involving the relevant surveys, cost estimates, corporate organization, and funding. The final enabling legislation was not passed until May 24, 1828. This was a cause for celebration throughout the area, including a special banquet for Mercer hosted by the Town of Leesburg.

On June 3, President John Quincy Adams appointed Mercer President of the C&O Canal Company, the successor to the languishing Potomac Company that Washington had established four decades before. Mercer then spent the next five years administering the project, which required attention to routing, funding, securing labor, and an infinite array of details. His involvement ended due to Andrew Jackson’s opposition to Federal support for the project, and to Mercer personally, in 1833.

Stopping the Slave Trade

In his last major writing, An Exposition of the Weakness and Inefficiency of the Government of the United States of North America, Charles Mercer excoriated slavery. In that work, which he published anonymously in 1845, he bemoaned the degradation of the slaves, by noting that the three million

human souls are a blank in creation, are worse than dead—they are slaves. … They stand not only fixed and sunk but lower and lower are they sinking in the scale of creation; no bright spot shows their features, though made in God’s own image. All the light that shine illuminates them not; all the ameliorations of society reach not them; no rational enjoyments embrace them; no law is enacted for them; no vote, no voice, no cry of joy issues from their dark and deep dungeons! (emphasis added)

Mercer considered slavery the “blackest of all blots, and foulest of all deformities.” Yet, as a Southerner who inherited a small number of slaves and represented a district with many slaveholders, Mercer was by no means dedicated to general emancipation. Indeed, like many in his day, he saw emancipation as dangerous if it meant free blacks remaining in their communities, and publicly expressed vile racist views about their moral character.

But Mercer was passionately committed to stopping the slave trade, which continued despite Congressional legislation outlawing it in 1807. Through a loophole in that law, even when slave ships were intercepted, state governments were the ones to deal with their fate—which, in cases like Georgia, often resulted in the “liberated” being sold into bondage, with the profit going to the state coffers.

Mercer’s approach to this travesty was two-fold. First, the United States should deploy to intercept the slave traders near the coast of Africa and enact strict enforcement by declaring the slave trade to be piracy. Second, the U.S. government should fund the resettlement of emancipated slaves to a colony in Africa.

Mercer’s first action in pursuit of these goals was to successfully put through a resolution in the Virginia Assembly in 1816 supporting the idea of “voluntary” colonization[12] and asking for aid from the Federal government in procuring a suitable territory beyond the limits of the United States as an asylum for blacks. The second was his joining in the formation of the American Colonization Society (ACS) in 1817.

Originally, the ACS included many leading abolitionists, as well as Whigs such as Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, and many others. Ultimately, the abolitionists left the movement, due both to the opposition by blacks who wanted to claim their rights as American citizens, and the fact that colonization did not challenge slavery’s continued existence.Yet, the ACS’s efforts were vigorously opposed by Southern plantation owners as a foot in the door for emancipation.

Originally, the ACS included many leading abolitionists, as well as Whigs such as Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, and many others. Ultimately, the abolitionists left the movement, due both to the opposition by blacks who wanted to claim their rights as American citizens, and the fact that colonization did not challenge slavery’s continued existence.Yet, the ACS’s efforts were vigorously opposed by Southern plantation owners as a foot in the door for emancipation.

Mercer succeeded in getting the responsibility for slaves liberated from slave ships transferred the Federal government, and Federal monies to be allocated for finding a homeland for them in Africa. (Liberia, today) He also succeeded in getting the slave trade declared as piracy (which meant punishable by death), and worked vigorously to expose the continuing evil practice.[13] Mercer passionately denounced the practice as “robbery combined with murder … for it was truly murder to kill a man by poisoning the air he breathed with the aggravated horror of a slow and loathsome death as to kill him by poisoning his food or planting a dagger in his heart.”[14]

Extending the Franchise

Extending the franchise to under-represented Virginians in the Western counties, Loudoun included, was the fourth major emphasis of Mercer’s career. He participated actively in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-30, fighting for reapportionment and expanding the vote to white non-freeholders (i.e., renters). Mercer condemned the current arrangement, which gave predominant representation to the Tidewater crowd, as “oligarchical.” At that time, a minority of less than a third of the state’s population governed the other two-thirds, because that third commanded more wealth and was thus given more seats.

Mercer and his fellow reformers wanted the number of delegates to be determined by the number of free white citizens, not wealth. Such a calculation would result in increasing representation of Virginians from the western counties. “Let us elevate the condition of that population in Virginia, which constitutes the bone and sinew and strength of every nation,” he said.

After an extensive and complex political battle, the reformers lost. They did succeed in getting the franchise for leaseholders of a certain income, and three more delegates for Loudoun, but the fundamental basis for representation still rested not on population but property ownership. They also succeeded in getting direct election of the Governor. But the reforms were insufficient to allow Mercer in good conscience to vote in favor of the new Constitution; in fact, 39 of the 40 delegates who opposed the new document were from the upper Piedmont counties and counties west of the Blue Ridge.

Not to be Forgotten

Support for the policies of Leven Powell and Charles Fenton Mercer in Loudoun County did not die out right away. Numerous Whig politicians were elected to Congress from this area, where they pushed for policies of internal improvements and national banking. That political legacy also likely played a role in shaping the split in the County during the Civil War, with the northern districts, like Lovettsville, voting against secession.

The post-war period, however, saw the consolidation of Democratic Party control in Loudoun, as well as the rest of the state, with the consequences of the lagging economic development and Jim Crow racism. The accomplishments of Loudoun’s Federalists were all but forgotten.

It is my hope that this review will once again raise them out of obscurity, along with the economic policies of the nation’s most prominent Federalist, Alexander Hamilton.

ENDNOTES:

[1] See The Southern Federalists, 1800-1816 by James H. Broussard, printed by Louisiana State University Press in 1978. Other books on Southern politics concur. Note that western Virginia at that time included the counties west of Loudoun and others further South that are now part of West Virginia.

[2] See Legends of Loudoun by Harrison Williams, published by Garrett and Massie in 1938, and reprinted by the Loudoun Museum.

[3] Voting was public, and some records do exist in the Loudoun County Clerk’s Office. Due to the closure of public buildings due to the virus, they are currently inaccessible.

[4] The book can be purchased on Amazon or from the publisher, www.iuniverse.com/Bookstore.

[5] Broussard documents this at length.

[6] Broussard’s study comes to this conclusion, and provides some analysis of votes on slavery measures, for example, to support his argument on that issue.

[7] Details on the nature of Mercer’s support are presented in a 1988 doctoral dissertation by Robert Allen Carter, entitled “Virginia Federalist in dissent: A life of Charles Fenton Mercer.” That lengthy document is the source for much of the description of Mercer’s career in this paper.

[8] Much of the detail included here on Powell’s life comes from an 1983 doctoral dissertation by Richard Joseph Brownell, entitled “Virginia Federalist: The business and political career of Leven Powell, 1737-1810.”

[9] The history here is interesting. Monroe was actually a favorite of Virginia Federalists in the presidential election of 1808, and played something of a bridge role between the parties in that period and later.

[10] This review of Mercer’s career relies on three major sources: 1) The Carter thesis, mentioned above; 2) the book Charles Fenton Mercer and the Trial of National Conservatism by Douglas R. Egerton: and 3) the work of my friend Franklin Bell of Bluemont.

[11] In fact, Washington’s Potomac Company differed from Mercer’s Canal in that it intended to make the Potomac River navigable up to the Ohio; the canal portions were only to circumvent insurmountable obstacles such as Great Falls. Mercer’s project involved establishing a Canal running parallel on the north side of the river. Mercer’s original name for it was the Union Canal, but it was ultimately named the Chesapeake & Ohio.

[12] While one could validly question whether all blacks sent to Liberia were there of their own volition, it is clear that many exercised their will by refusing to go—including Mercer’s own slave family.

[13] Note his 1821 Slave Trade Report, which reported startling numbers of slaves continuing to be brought out of Africa, including into the United States.

[14] Carter, p. 312.