Luther H. Potterfield and the Lovettsville Potterfields:

A Family Divided

By Edward Spannaus

(This is an edited version of talk presented to the Lovettsville Historical Society, on Sept. 20, 2015)

The Civil War period in Lovettsville is book-ended by two significant events– which both involved the Potterfield family.

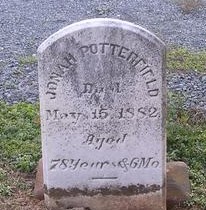

The first took place on May 23, 1861, the day of the referendum on the ordinance of secession. In the Lovettsville precinct, the vote against secession was 325 to 46. While the polls were open, ardent secessionist Jonah Potterfield hoisted a Confederate flag in front of his house, which was cut down by his nephew (and later Unionist intelligence agent) Charles W. Johnson. The soldiers at the polls arrested Johnson and forced him to put up another flagpole; Jonah then came up with another flag, and asked the soldiers for arms so he could protect it.

But that wasn’t the end of it. In October, Jonah was arrested – probably seized by Johnson and two other Unionists while on an errand in Harper’s Ferry. He was put before a military tribunal, and sent to the military prison at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. (If you go to Fort McHenry today, you can still see where Confederate political prisoners were quartered.) The charges against him, according to official military records were “Raising a rebel flag on his house and applying to the rebels for arms to defend it, &c.” On Dec. 2, he was transferred to Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor, a prison for “high-value” Confederate prisoners, both civilian and military, and sometimes called the “American Bastille.”

Among those already detained at Fort Lafayette by the time Jonah got there, pursuant to President Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, were the Mayor and entire city council of Baltimore, and Francis Scott Key’s grandson, an editor of a secessionist Baltimore newspaper, The Exchange. The editor of The Exchange, William Glean, was at Fort McHenry with Jonah, before they were sent to Fort Lafayette. Jonah was released on April 9, 1862.¹

The second event occurred at the end of the war, on April 5, 1865 – four days before Lee’s surrender at Appomatox – when the Confederate renegade and outlaw John Mobberly was lured to Luther Potterfield’s farm on Long Lane, about four miles from the town of Lovettsville, and shot to death. The capture-or-kill operation was set up by Luther H. Potterfield, who had approached the military command at Harper’s Ferry in late March, and proposed such an operation. Gen. Stevenson said he didn’t think it could be done, since it had already been tried, and Mobberly had already killed 31 Union men. Luther said he thought he could do it, if he could plan the operation himself. Stevenson ran the idea by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who approved, and then sent an elaborated proposal to Gen. Winfield Hancock of the Middle Division. Hancock sent an order approving the operation to Stevenson on April 2.

On April 3, Stevenson met with the team that was to carry out the operation: three civilians (Luther Potterfield, Jacob Boryer, and Charles W. Wright (a Hoysville farmer); and four soldiers, all Loudoun Rangers (Cpl. Samuel Tritapoe, Pvt. Mahlon Best, Pvt. Joseph Waters, and Sgt. Charles Stewart (the latter who, having been seriously wounded at Waterford a year earlier, was shot repeatedly and trampled by Mobberly after he had surrendered). Stevenson also provided extra revolvers for the civilians, and transportation to Berlin (Brunswick).

One way or another (there are a number of versions of the story — whether it was by the offer of a fine horse, a rivalry over a pretty girl, or blacks for Mobberly to capture so he could get a bounty), Mobberly and his sidekick Jim Riley were lured to Potterfield’s farm. Mobberly was shot and killed, and Riley escaped. The team took Mobberly’s body over the mountain to Harper’s Ferry, probably via the old road that ran from the end of Long Lane across the Short Hill to Ebenezer Church. Gen. Stevenson received a telegram of congratulations from Secretary of War Stanton.

A day or two later, Potterfield’s barn and its contents were burned in retaliation by Mobberly’s gang – and 50 years later, Luther was still trying to get compensation for the loss.²

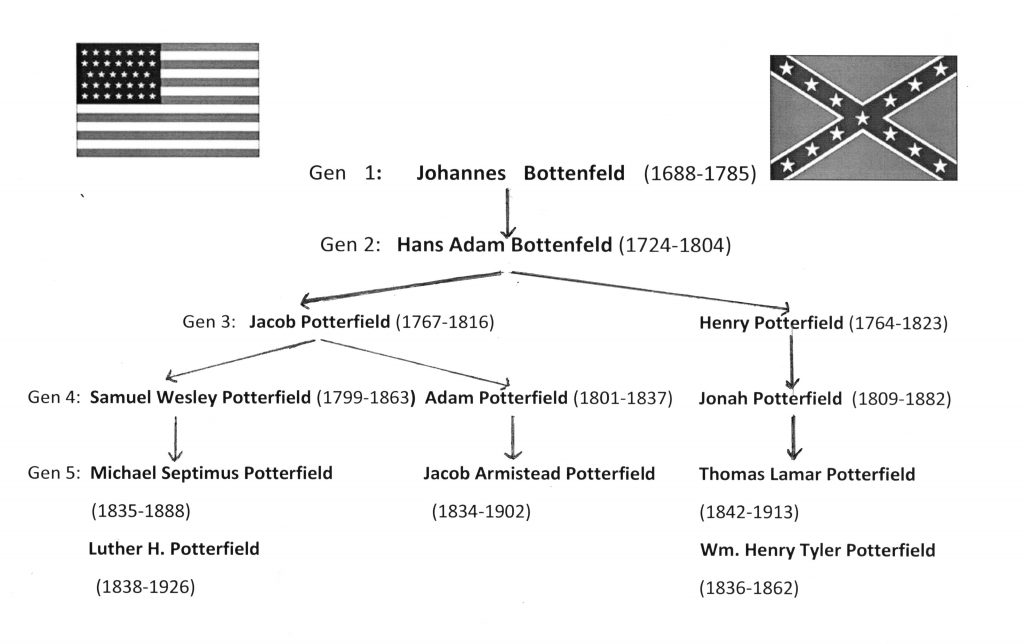

Jonah and Luther Potterfield were both descended from the same German immigrants – Johannes Bottenfeld and his son Hans Adam, who came to Pennsylvania from the German territory of Baden in 1750. Before telling more of Luther’s story, we will look at the family – and how it became so divided less than one hundred years later.

Johannes Battenfeld and his descendants

The founder of the Lovettsville Potterfield family, Johannes Battenfeld, was born in 1688 in Battenfeld, in the Principality of Hesse. By 1715, for unknown reasons, he found himself a bit further south, in Michelbach, Kreis Mosbach, near Heidelberg, in Baden which was part of the Palatinate, where he was married. Had he stayed in Hesse, he probably would never have come here, since almost the only Hessians who came here in the 18th century were the Hessian soldiers who were fighting under contract with the British Crown.

In 1750, he received permission to emigrate to the New Land with his wife, two sons Philip and Hans Adam, and three daughters, upon payment of the tithe (30 florins). This is about the tail end of the great Palatine emigration from Germany, which ran from 1710 to 1750. German emigration to the North American colonies slowed to a trickle with the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in Europe (French-Indian War in North America), and did not resume until 1830.

On August 28, 1750, having arrived on the ship Two Brothers, Johannes and his sons Phillip and Hans Adam, took the oath of loyalty at the court house in Philadelphia.

Johannes and family settled in Mannheim Twp. in York County, Pa. Hans Adam bought land there around 1755-60, and married Maria Elisabeth Pauster (Bowser) in 1754, at St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church in Hanover in York County; she died in 1767, possibly during childbirth. The brothers Philip and Hans Adam had land listed on the 1772 tax list in York Co.

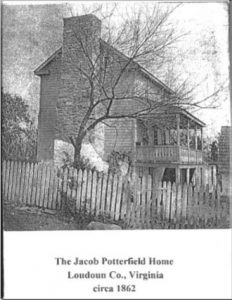

Around 1770-71, Johannes and son Hans Adam came to Loudoun County, Va. (while Philip stayed in Pa.) and they both lived here for the rest of their lives (Johannes died in 1785; Hans Adam in 1804.) Hans Adam bought 137 acres “at the foot of the mountain,” and another 28 acres nearby but not contiguous. We will come across tangled court proceedings involving these properties a hundred years later.)

It’s not known where either Johannes or Hans Adam are buried. They were members of the Lutheran Church (now New Jerusalem), and could be buried in the old church cemetery, but the church’s burial records are incomplete for that period.

During the Revolutionary War, Hans Adam supplied goods to the army, according to Loudoun County records (which list him as Adam “Potterfeilt”); this is considered ‘’patriotic service” and makes any descendant eligible for DAR/SAR.³

Hans Adam and Maria Elizabeth had eight children who grew into adulthood. Of these, two are of our immediate concern: Henry, born in 1764, and Jacob, born in 1767, both in York County, Pa. Others went back to Pennsylvania from Loudoun (some to around Bedford, Pa.), and others to Ohio. Henry is the father of Jonah Potterfield — what we can call the Confederate branch and Jacob is the father of Samuel Wesley Potterfield and another Adam Potterfield – the Unionist branch. (See chart)

The first three generations were Lutheran, both in Pennsylvania, and here. (There was always some back-and-forth between the Lutheran and the German Reformed Church; baptisms and marriages might be performed by whichever minister happened to be in the area, since neither church in Lovettsville had full-time pastors until the 1830s.)

The Henry-Jonah line:

With Jonah (1809-1882), we see the branching off of part of the family into the Presbyterian church in Lovettsville, of which Jonah was a founder (in 1833) and a senior elder for the rest of his life. However, to show how fluid these lines could be, Jonah’s marriage to Amanda Thrasher in 1834 was performed by the Lutheran minister. It seems that Jonah’s family seemed to have made up the core of the Presbyterian church during most of its existence; as late as 1915, two of its three elders were Jonah’s sons Elias and Luther T. The other was a Frazier, who was married into Jonah’s family (daughter Sarah married Samuel Frazier in 1857).

The Presbyterian church in Lovettsville was actually a split from the German Reformed, both denominations being of the Calvinist persuasion. The Rev. E.C. Hutchison had been preaching at the Reformed church in Lovettsville, and then took a group of people from the Reformed church to form the Presbyterian Church. In the 20th century, after the demise of the Presbyterian church, most of Jonah’s children and grandchildren (such as Thomas Lamar’s family) were again associated with the Reformed Church (now St. James United Church of Christ).

What role did church affiliation play in the Civil War? Although there is not a perfect correlation, you will see that the Confederate Potterfields tended to be on the Presbyterian-Reformed (Calvinist) side of the family, and the Unionist Potterfields on the Lutheran side. 4

Jonah was the only one of Henry’s children who stayed in Lovettsville; all the others removed to the western states.

In the May 1861 secession referendum, Jonah Potterfield and his son William voted for secession. Samuel Potterfield and his sons Luther and Septimus voted against.

We have already heard the story of how, later that year, Jonah was made a political prisoner of the federal government for his outward display of Confederate sympathies.

Two of Jonah’s sons – Thomas Lamar Potterfield, and William Henry (Harrison?) Tyler Potterfield – enlisted in the Confederate States’ army, both in the 7th Virginia Cavalry (Ashby’s Cavalry). Both were Sergeants in Company A. (There are stories that Jonah also fought with Ashby’s Cavalry, although there doesn’t seem to be any official documentation of this that anyone has found.)

William H.T. Potterfield is the only Potterfield, besides Luther H., who is recorded as having served in the militia prior to the Civil War. He was a sergeant in Jones’s Company (Hoysville) of the 56th Va. Militia during the mobilization after John Brown’s raid.

William died as a result of wounds suffered at the first Battle of Brandy Station, on Aug. 20, 1862. Some say he died in a hospital, others say he died in his brother’s arms; both could be true.

There is a grave marker for him at the old Reformed cemetery, but he is not actually buried there. Dottie Gladstone reports, based on an interview with two of Thomas’s daughters, Miss Dot Potterfield and Mrs. Winnie Myers, that Jonah and Thomas returned to Brandy Station after the war, but were never able to find William’s grave.

Thomas Lamar Potterfield, who survived the war, is better known to us as a prominent Lovettsville citizen. Like his brother, he enlisted in Ashby’s Cavalry on May 1861. He was taken prisoner at some point, and paroled in May 1865, after Appomattox. He got married after the war, in 1867, to Sarah/Susan Coblentz; they were married in Frederick County. Many of his descendants are still among us today – including Fryes, Hickmans, and Groves.

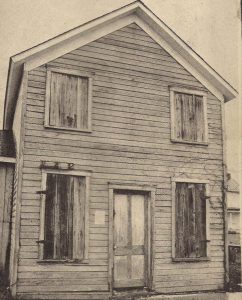

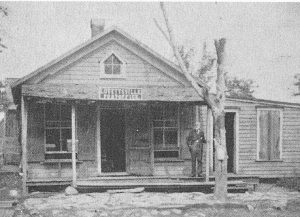

If you have ever been in the Lovettsville Museum, you have been in the building that once housed Thomas Potterfield’s meat store – part of a much larger slaughterhouse complex described in Glenn Grove’s monograph.

Thomas’ house is the next-door building at 2 East Pennsylvania, between the Town Hall/Museum and South Church Street. Thomas and his sons also had a thriving cattle business, some of which was located on Luther Potterfield’s “back lot” at Locust St. and Pennsylvania Avenue.

In 1899, Thomas was at the center of a partisan election dispute. On May 25, 1899, an election was held in which Thomas L. Potterfield (a Democrat) was the only registered candidate for Commissioner of the Revenue for the Lovettsville District. He got 1946 votes, and a write-in candidate, Republican Laban C. Grubb, had 246 votes. A suit was filed by at least 16 citizens challenging his election, on the grounds that Thomas Potterfield was the Registrar of Voters for the Lovettsville Precinct at the same time, and thus was legally ineligible, because, under Virginia law, it was illegal to hold the position of Registrar and to run for another office at the same time. The plaintiffs, led by L.W. Hickman, an active Republican, asked that the election be annulled, and that Grubb be declared as the winner of the election. The County Court did vacate the election, declaring that there was no valid election, but also ruled that Grubb, who had not rbeern egistered as a candidate, was not entitled to the office. On appeal, the Circuit Court of Loudoun County upheld the County Court’s ruling. 5

That Thomas L. Potterfield would have been a Democrat, and Luther H. Potterfield, a Republican, makes sense, since those party lines tended to follow the Confederate-Union divide from the Civil War period. Accordingly, the Lovettsville precinct was the most consistently Republican-voting precinct in Loudoun County in the days when the old Democratic Party dominated Virginia.

The Jacob-Samuel line:

We’ll now look at the other side of the family, the line that ran through Jacob Potterfield and Samuel Wesley Potterfield. Samuel, born in 1799, and Jonah, born 1809, were contemporaries and first cousins.

Jacob Potterfield, brother of Henry, had seven known children: Samuel; Adam (married Mary Stream); Mary (married Michael Wiard); Elizabeth (married Thomas Thrasher); Catherine (married Adam Shober); Leah (married Peter Virts); and Jacob (married Sarah Johnson).

And, just to show that the church lines were not hard and fast, four of Jacob’s seven children appear to have become Presbyterian: Adam, Mary Wiard, Elizabeth Trasher, and Jacob.

Besides Samuel, another of Jacob’s sons, Adam (born 1801) is also relevant to our inquiry. He married Mary Strahm/Stream at the Lutheran Church in 1827; one of their children was Jacob Armistead Potterfield, who fought with the 1st Potomac Home Brigade Infantry, later known as the 13th Regiment Md. Infantry, in the last year of the war. Many Loudoun men fought with the PHB, both its infantry and cavalry units (Cole’s Cavalry). Jacob was an active member of the GAR after the war, and he named one of his sons Ulysses Grant Potterfield.

Samuel Potterfield married Catharine Everhart at the Lutheran Church in 1827. She lived until 1846, and they had at least seven children, six of whom lived to adulthood. (One, Samuel Wesley Jr, died at age 5.) The family was associated almost totally with the Lutheran church, except that their first son, Silas, was baptized at the Reformed Church around 1829 or 1830, and five-year old Samuel Wesley Jr. was buried at the Presbyterian church.

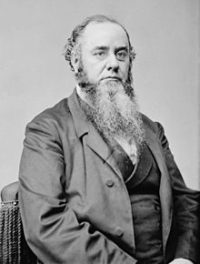

Two of Samuel’s sons were active Unionists. Michael Septimus Potterfield (1835-1888) was a corporal in the Loudoun Rangers, Co. B. He married in 1856, before the war, to Alcinda Edwards, at the Lutheran church. The second was Luther Howard Potterfield, born 1837, who is the primary subject of this talk.

Luther H. Potterfield:

We have already discussed Luther Potterfield’s role in the operation to capture-or-kill John Mobberly in April 1865. This was not Luther’s first involvement with the military; the first was serving in the County Militia.

We have previously noted William H.T. Potterfield’s participation in the Loudoun Militia, the 56th Virginia Militia, at the time of the John Brown raid in Harper’s Ferry in 1859. William Tyler was in the Hoysville company.

Luther was a private in Capt. Armistead Everhart’s Company of the 56th militia, mostly Lovettsville men, at the time of the John Brown mobilization, and was later a Lieutenant. After secession, Everhart marched 50 of his men to the federal camp at Sandy Hook, Md., on July 17, 1861, and offered their services to the U.S. Army. Within 48 hours they were deployed scouting and guiding Union troops into Loudoun.

A week later, on July 25 – while still across the river with Everhart’s company in Weverton — Luther Potterfield wrote to Maryland Congressman Francis Thomas (who had helped organize the Potomac Home Brigade) asking for information about how to take the Lovettsville Company of the 56th Militia, and bring it back to Loudoun “to protect our homes” from the rebels who are “running over our Parents.” He said they didn’t want to join the Maryland regiments, but they wanted to return home and organize there. “We did not go for the South but we go for the government,” he wrote.

The Union army was not yet ready to commission a unit in Virginia, perhaps because they expected a quick victory. In March 1862, Luther Potterfield made a second try, this time writing to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton from Knoxville, offering to raise a regiment of home guard, and promising that he could raise 200 men in two weeks’ time. “Mr. Stanton, all we want from you is arms and we will defend Ourselves,” he wrote, adding that he had a recommendation from General Nathaniel Banks, the Union commander across the Potomac in Maryland.

The Union Army was still not ready to organize a partisan ranger group in Loudoun, but by June, Secretary Stanton was ready, and he authorized Waterford miller Sam Means to organize an independent company of rangers, which became known as the Loudoun Rangers.

Luther did not join the Loudoun Rangers. After the war, he said that he thought he could do more for the Union cause by serving as a scout for the Union army, which he did: he served as a scout and intelligence agent for the Union military from 1862 to April 1865, particularly for Col. Geary of the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry, and Harper’s Ferry District commander Gen. Stevenson. He said he captured one of Elijah’s White’s men (named Cooper), and guided Union forces who captured others, risking his life on a number of occasions.

On November 17, 1863, Luther’s father Samuel died of dysentery/typhoid fever, after having been held prisoner by the Confederates. (The circumstances of Samuel’s arrest and imprisonment are not known, but the church burial record also gives his cause of death as typhoid fever.)

On June 28, 1864, Luther asked the federal military authorities for leave to reopen his slaughterhouse, his only means of support. It had been closed by an order terming it a nuisance.

On August 15, 1864, Luther filed a complaint with Justice of the Peace Thomas J. Cost against four individuals for property taken from him, including bedding, clothing, cloth, a bridle, and an accordion.

In late March of 1865, as we’ve discussed, Luther Potterfield proposed to Brig. Gen. John D. Stevenson that he be authorized to carry out a capture-or-kill operation against the renegade Mobberly –who had been terrorizing and brutalizing Unionist civilians. On April 3, Gen. Stevenson authorized the Mobberly operation, which was carried out on April 5. Afterwards, Luther went to Harper’s Ferry, then rode to Winchester to see Gen. Hancock, and then back to Harper’s Ferry. Stevenson gave him a pass to Berlin (now Brunswick). Potterfield was there two days later, when his barn was burned by Mobberly’s gang; he later said he watched the fire from across the river. The civilians who participated in the Mobberly operation were each paid $500 out of the secret service fund “for special service rendered to the United States Government in the killing of John Mobly, a notorious guerilla….”

In what was perhaps another award, on April 29, Gen. Stevenson ordered that there was to be no interference with Luther Potterfield starting a distillery for making whiskey; this was after Luther had written to Stevenson advising him that he intended to start a distillery and requesting that soldiers be prohibited from interfering with it.

On June 5, 1865, Potterfield sent a letter to Gen. Hancock, acknowledging receipt of the payment for the Mobberly operation, and stating that Gen. Stevenson had advised him that, if he would make an application in the proper form, he could seek recompense for the burning of his barn. 6

In the late summer of 1865, when things started getting back to normal, and the courts opened again, Luther began to seek compensation for the burning of his barn, and he also was concerned to defend himself against murder charges which the remnants of Mobberly’s gang were contemplating bringing against him. On August 14, he wrote to Gen. Stevenson seeking reimbursement for the barn. And on August 29, he send another letter to Gen. Hancock, in which he stated that “I have been accused of killing the guerrilla John Mobberly without any authority from the Commanding General at Harpers Ferry Va.,” and he recounted how Gen. Stevenson had received the order from Hancock on April 2, that Stevenson gave Potterfield a verbal order on April 3, and “we shot him” on April 5. “As I am likely to get myself in trouble for not having a written order from General J.D. Stevenson, you would do me a great favor by sending me a written order to prevent my arrest and trial for murder… There is a party trying to get evidence against me now….” 7

Meanwhile, Luther had filed charges with the county court on August 21, for the burning of his barn and its contents, and on September 8, the Commonwealth Attorney filed criminal charges against three of Mobberly’s men – James Riley, James Tribby and John Tribby — “for feloniously burning a barn and stealing and carrying away goods on the 7th day of April 1865….” On August 30, Luther filed the same charges against George Chamblin. 8

Witnesses for the prosecution against Riley, et al. were Jacob Boryer, Mary Potterfield, Luther Potterfield, and Solomon Derry. They were summoned to appear in court on September 1, then again October 1 as the case was continued, then again on November 1. Others summoned to appear were Samuel George, Charles W. Johnson, Frank Myers and Elijah White (perhaps to testify whether or not Mobberly was acting under military orders; in fact, he was considered a deserter.) John Axline (son of David) was another witness in the Court of Claims case; he said he saw some of Mobberly’s men coming away from the burning barn.

On November 13, 1865, Luther dropped the charges, with the case treated as Nolle Prosequi. Potterfield later said he was “persuaded” to drop the charges, and he decided to seek reimbursement from the federal government – a course which he would then pursue for the next 50 years. Decades later, he stated that “I took steps to bring suit in the State court but was advised to drop it as it was the duty of all good citizens to do what they could to promote peace, and that such a suit would stir up a disturbance in the neighborhood.”

Meanwhile, in response to his August 14 letter, Gen. Stevenson endorsed Luther’s request, and sent it on to Gen. Winfield Hancock, who wrote back to Potterfield on November 15. Hancock said that Stevenson had confirmed that he had made an arrangement with Luther Potterfield to capture or kill Mobberly, and that Potterfield should be reimbursed for his losses. Hancock also said that Stevenson had learned that some members of Mobberly’s band wanted to prosecute Potterfield for murder, and Hancock says he trusted that the military would protect Potterfield. Hancock forwarded the request to The Adjutant General (TAG), and recommended that Potterfield be reimbursed out of secret service funds.

Apparently that communication got “lost in the mail,” for in 1870, when Potterfield renewed his claim, the office of The Adjutant General said that had never received it. Decades later, in 1910, TAG Fred C. Ainsworth said that the War Department concluded that Luther Potterfield had performed his work in accordance with instructions from an Army officer, and that his property was destroyed by the Mobberly band in revenge – but that the case did not appear to be one for executive action, and that only the legislative branch was competent to grant relief.

This was despite the fact the Gen. Stevenson had written, in a September 28, 1865 letter, that while in command at Harper’s Ferry, he had made an arrangement with Potterfield “to capture or kill a notorious guerrilla named John Mobley,“ and that Potterfield had expressed fears that Mobberly might burn his property. “I directed him to go ahead and do the work and trust to the justice of the government to reimburse him for such loss, and I had no doubt it would be properly done,” Stevenson had written.

Much later, in 1887, the U.S. House of Representatives authorized payment to Potterfield of $2,500. 9 The Department of Justice, ever faithful in defending government funds, asserted that Potterfield’s loyalty was in question, but it acknowledged that there was nothing in the Confederate archives that would shed any light on any disloyalty. The Treasury Department informed the Justice Department that Luther Potterfield had voted against secession. Finally, the House referred the case to the U.S. Court of Claims, which asked that both Potterfield and the Justice Department submit briefs and proposed findings of facts. As late as 1915, the Court of Claims concluded on technical grounds that the matter should go back to Congress. It doesn’t seem that it was ever resolved, or that Luther Potterfield ever received compensation for the burning of his barn and its contents.

Family legal matters

This is not the only court action in which Luther Potterfield was involved.

Starting in 1855, there were two actions involving the estate of Michael Everhart, Luther’s grandfather, and his mother’s father. At that time, Julius and Mary (the only children of Samuel and Catherine who were over 21) brought an action in Chancery Court, asking that a guardian ad litem (i.e. just for that case) be appointed for the underage Septimus, Luther, and Catharine, and that the court decide how to dispose of two tracts of land left to them by the division of their grandfather Michael Everhart’s estate through their mother, who died in 1846. One tract is 283 ¾ acres adjoining properties of Wiard, Kalb, etc.; the other is a 10-acre wood lot. They argued that it would not be convenient to divide the property, and better to sell it. The court appointed their father Samuel as commissioner to sell the two parcels. The the court appointed other commissioners – John Grubb, Emanuel Axline, and Jacob Smith – who agreed that partition was not convenient, and it were better to sell the land. 10

Another case, brought in 1857, grew out of Michael Everhart having conveyed to Samuel tracts of land and personal property for the benefit of Michael’s children, including Catherine and John Everhart. John was described as being of “very intemperate habits,” who did nothing to support himself, and spent all his earnings on “ardent spirits.” John lived with Samuel for only six weeks, had no permanent home, and Samuel couldn’t control him. It was determined that someone better suited than Samuel should be the trustee and hold the property. John’s brother Joseph was willing to become the trustee. Michael Wiard (Samuel’s brother-in-law, married to Sam’s sister Mary) testified that John’s habits were bad, especially getting drunk, but that he didn’t consider Joseph to be suitable as a trustee. In 1860, a court order noted that John was dead, and the case was closed. 11

Another, protracted case involved two of Luther’s grandparents, Jacob’s wife Elizabeth, and the estate of Michael Everhart. This involved a promissory note Michael Everhart had made to Elizabeth. The case was initiated in 1856, if not earlier. Elizabeth died in 1859, and the case was apparently never resolved.

The Loudoun County courts were closed during the Civil War, and didn’t reopen until the summer of 1865. In September 1866, the court dismissed a long list of cases that had languished during the War; this included the Elizabeth Potterfield case against Michael Everhart’s estate, cited above.

As soon as the courts reopened, Luther was involved in a number of other legal cases, growing out of the death of his father Samuel, who had died intestate – without a will – in 1863. On September 11, he was appointed administrator of his father’s estate; his sureties – to guarantee his performance – were Thomas J. Cost, James M. Downey, and Charles W. Johnson. Appointed to inventory and appraise the estate, were James Frazier, James Booth, John G.R. Kalb, Charles W. Johnson, and Michael Wiard.

Now, here comes the rather unsettling part of the story. It seems that, at some point, three of Luther’s brothers and sisters had been determined to be insane, or “lunatics” as it was termed at the time. (Mention this to old-timers around here, and most will immediately bring up the “in-breeding” which was prevalent in the early years of this area.)

Luther seems to have been the one who took responsibility for them. In November 1865, he was appointed by the court as “committee” (trustee) for Julius, Silas and Catherine. His sureties were Lewis Mann, Samuel George, and Jacob Boryer. He also filed an action in Chancery (equity) in 1865, in three capacities – for himself, as trustee for the three “lunatics,” and as administrator of his father’s estate – asking the court to decide on the disposition of Samuel’s real property. In December, Luther filed a motion with the court, asking that a guardian ad litem be appointed to represent the interests of the three in that proceeding. A.J. Bradfield, the clerk of the court, was appointed.

What Luther wanted, he told the court, was to buy out Mary and Septimus, so that he could keep the farm and care for his three mentally-disabled siblings. But in 1867, Mary and Septimus brought another action asking for a partition of the 130-acre “home tract”, either by dividing it, or by sale. Guardian ad litem Bradfield answered for the “lunatics:” by reason of mental infirmity, they neither admit or deny the allegations, and they submit their interests to the protection of the Court. According to an agreement dated September 24, 1867, all agree to sell all the “home tract” and the mountain wood lot. A commissioner was appointed to sell the properties. He placed newspaper ads for the sale of the home tract on December 31, 1867, describing it as containing 130 acres, and including a log dwelling, smoke-house, milk-house, corn-house, wagon shed & other improvements, plus a young orchard of prime fruit, and woods running up the side of the Short Hill. The ad stated that Luther Potterfield resides at the place and will show it to prospective buyers. An auction was held in front of Wenner & Eamich’s store in Lovettsville. The highest bid was an offer by Joseph Waltman which was deemed “wholly adequate” and the larger property withdrawn from sale, although Waltman did get a 17-acre wood lot. John C. Bush (a friend of Luther) made an offer later for the home tract and put down a deposit, which was returned to him. An offer by cabinet-maker Jerome W. Goodhart was accepted. When Goodhart failed to make full payment in the time required, an Order to Show Cause was issued against him; he was saved when H.N. Tavenner (son-in-law of Robert Johnson) put up money for the land, which was later returned. It appears that ultimately, Goodhart got the larger tract in 1872.. The court issued final decree on April 7, 1872, paying $163.88 to each of Samuel’s six children. 12

What happened to the three mentally-disabled siblings? All the family genealogies that I’ve seen say nothing more about them: they just seem to disappear. With the home property being sold, Luther had to move into town, and he was living with the Eamich family by 1870, and was working at Eamich’s store. There were six adults in what amounted to a four-room house (the brick portion of what is now 30 E. Broad Way), so it’s not surprising that none of his siblings were with him.

The guardian-account files at the county court give some indication regarding the three “lunatics.” Julius appears to have died in 1876, in a hospital in Frederick. The last accounting for Silas is in May 1869, so he either died, or left the area. Catherine was living with various people, including her sister Mary Bantz or Bontz); the Bantzes were paid for board, as was the Arnold family and some others, into the 1880s.

Events in Luther Potterfield’s post-war life:

After the Civil War, Luther moved into the town and became very active in civic and political affairs, as well as in the Lutheran Church. He held a number of elected and appointed positions. He was a Republican – as were most former Unionists – and was a delegate to the Readjuster statewide convention in 1880. 13 He worked as a merchant through the 1870s and 1880s, and then was Postmaster and Assistant Postmaster until his retirement. Here are some of the key events:

1866 When the Freedom Lodge No. 199 was established in Lovettsville, Luther Potterfield was a charter member.

1868 – Luther is one of three Trustees of Freedom Lodge No. 199, which bought Lot No. 12 from Peter A. Frye for the Masonic Lodge. Others were John C. Bush and Thomas J. Cost. Construction began soon, since the date on the cornerstone is 1869. The building was also used for a school (the Lovettsville Academy, which became the white public school), and was also used as the Town Hall.

1870 – The federal census shows Luther living with the Frederick Eamich family in the town, and working as a clerk for dry goods merchant (i.e. Eamich’s store).

1871 Nov 28 – Luther and Kate Eamich were married at the Eamich residence by Rev. Xenophon Richardson of the Lutheran Church; Kate’s brother George & his wife were witnesses.

1872 – Luther’s and Kate’s daughter Clara is born; she became Clara Dunlap, and lived until 1947.

1874 May 28 – Luther was elected (tax) collector for Lovettsville Township; his sureties are Gideon Housholder, George F. Eamich , J.W. Goodhart, Samuel Smith, and Alan Carnes.

1877 – Luther and George Eamich jointly file an action against John Bontz regarding a note they purchased at bankruptcy auction; this involved the estate of Joseph Waltman, of which W.W. Wenner was the executor.

1878 May 2 – Luther bought the house next door to the Eamich house (now 32 East Broad Way), in which Luther and Kate lived until Luther sold it in 1924, nine years after Kate’s death. He also bought the rear lot, which later was used as Ed Potterfield’s cattle pen, and part of which is now the parsonage for Mt. Olivet Methodist Church.

1880 Jan – Luther was commissioned by the Governor as Justice of the Peace.

1880 – The census states Luther Potterfield’s occupation as dry goods merchant.

1880 May Luther was a Delegate to the Readjuster Convention for the Lovettsville District. 13

1881 Oct. 10 – Luther is appointed Election Judge for Lovettsville Precinct.

1886 and 1890-92 – Served as Trustee of New Jerusalem Lutheran Church

1888 March 5 – Commissioned by Governor as Notary Public; sureties are Peter A. Frye and Edgar Littleton

1889-93 – Federal appointment as Lovettsville Postmaster (under GOP administration), and his oocupation is listed as Assistant Postmaster in the 1900 and 1910 census.

c. 1890 – Becomes Superintendent of Lovettsville Union Cemetery; a New Jerusalem church newspaper described Luther Potterfield as “the indefatigable superintendent” of the cemetery.

c. 1890 – Becomes Superintendent of Lovettsville Union Cemetery; a New Jerusalem church newspaper described Luther Potterfield as “the indefatigable superintendent” of the cemetery.

1892-96 – Served as deacon of New Jerusalem. He also sang in a quartet at the church. And sometime between 1890 and 1910, Luther and Kate bought a piano, which was shipped by rail from the Willig music company of Baltimore. 14

1915 — Kate died, and was buried at Union Cemetery

1924 Aug 20 Luther executed his will: $1000 to Mary K. Wire, w/o George E.; $1000 to Stella Wire xv w/o Charles E. (dec’d); $300 to Lovettsville Union Cemetery for Lots 112 and 177; some furniture and residue to daughter Clara E. Dunlap (52 y/o), who lived in Blackstone Va., wife of James A. Dunlap. Clara is the only heir.

1924 – Luther sold his house to Selby Brown, moved to Washington, D.C., and was living at 254 10th St. S.E. We don’t know with whom he was living.

1926 Jan. 6: Luther died in Washington, D.C.; his funeral was held at New Jerusalem, and he was buried in Lovettsville Union Cemetery.

How divided was the Potterfield family really?

There is no question that attitudes toward the Civil War lasted for generations. Tyler Potterfield of St. Augustine, Florida, tells a oouple of stories which shed some light on this. He notes that his father Hugh (a great-grandson of Jonah Potterfield), had a print of Harper’s Ferry over his desk for many years. When asked about it, he would reply with passion: “The Confederates gave the Yankees their worst whipping at Harper’s Ferry, capturing 12,000 Union troops.”

On the other hand, there are some indications that perhaps, the family wasn’t as divided as it appears: Tyler Potterfield also tells the story of visiting Lovettsville in 1986. When he stopped at the store – probably McClain’s – he was told “We haven’t had a Potterfield in this store in ten years — welcome!” He was given directions to the old Reformed Cemetery where many of the Potterfields are buried.

Two volunteers were in the cemetery cleaning up, and one said to Tyler: “I heard there was a Potterfield in town” – which shocked Tyler, since he’d only been in town for about half an hour. The man went on: “My German ancestors came here in 1730, and the Potterfields arrived 40 years later, and we haven’t had any money since they got here.” This was apparently a reference to the Potterfield’s reputation for shrewd business practices, and, Tyler notes, the man was very serious about this. (And it was accurate: according to family histories, the Potterfields did arrive in Loudoun County around 1770.)

The other thing the man did, was to ask Tyler if he knew the story about his great-great grandfather Jonah Potterfield coming back from the fighting at Richmond during the Civil War, and shooting the hated local terrorist and bandit John Mobberly — the reason for this being that Mobberly was bringing discredit upon the Southern cause.

Now, although it is unlikely, from the known evidence, that Jonah was involved in the actual shooting of Mobberly, it is quite possible that he could have been involved in luring Mobberly to Luther Potterfield’s farm — since there is no firm evidence as to how that happened, and there are in fact a number of different versions of it that have come down over the years. 15

In any event, I offer this story not for the truth of the account, but for the fact that the story was being told some 30 years ago, and was apparently sincerely believed by its teller.

Also of interest, is that Luther’s will names only three people: his daughter Clara, Stella Wire (a daughter of Thomas Lamar Potterfield), and Mary Wire (Stella Wire’s daughter-in-law). And Thomas Lamar’s son Edward operated a cattle pen on Luther ‘s back property in town. Thus It would appear that Thomas and Luther were not estranged in the decades after the war.

So it just might be the case, that the two sides of the family have more in common than my brief history of the family would otherwise lead you to conclude.

Endnotes:

1 The Jonah Potterfield story is recounted in Chamberlin & Souders, Between Reb and Yank, pp. 39, 74.

2 The Mobbery affair is told by many sources. The most reliable are Between Reb and Yank, pp. 330-331; Luther H. Potterfield’s U.S. Court of Claims case file, No. 15, 745, NARA Record Group 123 (on file at Lovettsville Museum).

3 Loudoun County Circuit Court, Revolutionary War Papers, p. 95.

4 To get an idea of the Confederate-Union divide in the churches (keeping in mind that many Civil War veterans left the area after the war), we can look at the local cemeteries. The known ratio of Confederates to Union in the old Reformed Cemetery is 6:2, and Confederate Jonah Potterfield is the only known Civil War soldier (if he was, he has no service record) in the old Presbyterian cemetery. Lovettsville Union Cemetery (the “union” being of the churches) has a CSA-USA ratio of 11-4. The old Lutheran cemetery is the only cemetery in Lovettsville with more known Union soldiers (4-2) than Confederate. In fact, the Lutheran church in Lovettsville was overwhelming Unionist; its membership produced about 30 Union soldiers, and only a few Confederates.

5 Loudoun County Order Book 29, p. 451, and Book 30, p. 9; Loudoun County Misc. Papers, 1899; Alexandria Gazette, Oct. 20, 1899, p. 2; Free Lance (Frederickburg), Oct. 24, 1899, p. 2

6 L. Howard Potterfield letter to Hancock, 5 June 1865, NARA Record Group 109, Microfilm 435; accessed on Fold 3.

7 Luther H. Potterfield letter to Hancock, 29 August 1865, NARA Record Group 109, Microfilm 435; accessed on Fold 3.

8 Loudoun County vs. James Riley, James Tribby, and John Tribby, Loudoun County Criminal Papers, 1865-013.

9 The Congressional bill stated: “That the Secretary of the Treasury be, and he is hereby authorized and directed to pay, out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, to Luther H. Potterfield, of Loudoun County, Virginia, the sum of two thousand five hundred dollars for services rendered at the request of Brigadier-General J.G. Stevenson, United States Volunteers, and for property destroyed by Mosby’s band during the late war between the States.” Cited in Potterfield’s U.S. Court of Claims case.

10 Loudoun County Chancery Case M1166.

11 Loudoun County Chancery Case M432.

12 Loudoun County Chancery Cases M881 and M2082.

13 The Readjusters were a black and white movement including many Republicans, which was organized as a political party in 1879 and took control of the General Assembly (both the House and the Senate) that same year. They were formed primarily to stop the diversion of the public school funds to pay Virginia’s pre-war debt. For more on the Readjusters, see the 2019 edition of the Bulletin of Loudoun County History.

14 I know this because I found part of the piano shipping crate in one of the outbuildings on Potterfield’s town property, which my wife and I have owned since 1986.

15 Another story, passed through descendants, is that Confederate soldier Christopher Columbus “Lum” Wenner, of White’s Commanches, was involved in the killing of Mobberly; one reason given as to why Mobberly’s former comrades would have turned on him, is that he was stealing slaves and selling them to the Union army for a bounty. Thanks to Fran Wire and Sam Kroiz for this insight.