By Michael Zapf

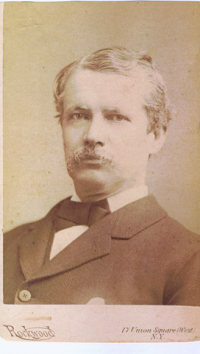

In our February 2020 Newsletter we introduced Dr. James A. Willard, who resided and practiced in Lovettsville from 1867 until his death in 1906. Two sources of information give us in-depth insights into the man and his time.

The first source is a published genealogy entitled Willard Memoir or the Life and Times of Major Simon Willard: with Notices of Three Generations of the Descendants, and Two Collateral Branches in the United States . . . by Joseph Willard, published in 1858 in Boston by Phillips, Sampson and Company. In this study, the author acknowledges the contribution of “my friend James Willard, M.D. of Jefferson, Frederic County, Md. Who provided the background of the Maryland Willards.” Joseph Willard concludes from the information provided by Dr. Willard that the Maryland Willards are unrelated to his subject Major Simon Willard, a New England Revolutionary War patriot. He nevertheless includes a section on the Maryland Willards based on the information supplied by Dr. Willard — including the following narrative supplied by the good doctor:

. . . There is nothing in their history to ennoble the name, or upon which one could base any pretension to an exalted pedigree. They were men, however (and I refer particularly to Dewalt, his sons and grandsons), just, scrupulously honest, independent in the widest allowable signification, ready at all times to protect the weak, hating dissimulation, and speaking always as the heart would prompt.

They were uneducated men; not, strictly speaking, illiterate, but without any claim to erudition.

My grandfather Elias, from what I have heard respecting him, and from what I have seen of his chirography, was superior in scholarship to any of his children. For the time in which he lived (and I speak of the time as having a necessary connection with the place and persons of his home and neighbors), he was an extraordinary man. The place at that time was a wilderness; and the settlers were rude, ignorant, hardy, and removed but few degrees from savage life. . . .

. . . Thirty-one years have flown since his body was given to the dust, and yet there remain anecdotes enough to invest his name with the romantic glitter of a legendary hero. . . .

The Willards of the present day are all men of character and respectability, although unknown to fame. Most of them are agriculturists, some are merchants, some professional, and some devoted to the mechanic arts.”1

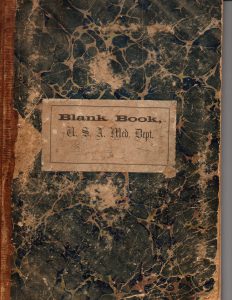

The second source are the Willard Journals in the Lovettsville Historical Society archive, another primary source of information on the life and character of James Willard. They are also a valuable resource for information on the First Maryland Infantry, Potomac Home Brigade, the names of soldiers of that brigade sick or wounded at Harper’s Ferry military hospital, the details of provisioning the medical facilities, the names of Lovettsville resident patients both black and white, as well as a story of a prodigal son.

The second source are the Willard Journals in the Lovettsville Historical Society archive, another primary source of information on the life and character of James Willard. They are also a valuable resource for information on the First Maryland Infantry, Potomac Home Brigade, the names of soldiers of that brigade sick or wounded at Harper’s Ferry military hospital, the details of provisioning the medical facilities, the names of Lovettsville resident patients both black and white, as well as a story of a prodigal son.

There are three journals in the archive; the earliest is ledger labeled “Blank Book, U.S.A. Med. Dept.” It begins with an entry dated Monday, November 21st 1864 and records provisions requisitioned for the military hospital at Harper’s Ferry where Dr. Willard served as Assistant Surgeon. In this entry he accounts for 25 men and one woman and requisitions Pork, 50 rations, making 371/2 pounds; Fresh Beef, 200 rations, making 250 pounds etc. There is a special requisition for 2 woolen, gray knit shirts and four pairs of woolen socks for Joseph McCoy, Hospital Cook. The mundane minute details of military hospital administration written in an elegant hand.

Unexpectedly the entry for Friday, November 25th reveals another facet of Dr. Willard. Here he quotes from Merle D’Aubigne’s monumental History of the Reformation in the Sixteenth Century:

. . .Pelagius asserted that man’s nature was not fallen that there is no such thing as hereditary evil, and that man having received power to do good has only to will in order to perform it. . .

The quotation above is just an excerpt of a series of quotations on this subject from this work and are the first indications of deeper thoughts and values that are found in later entries.

The normal administrative requisitions and accountability records of December 1864 are interspersed with notes and verbatim correspondence concerning being mustered out of the military and resuming his medical practice as a civilian.

Thursday, December 15th, 1864. Rode to the Ferry this morning for my Muster out. . . .to Lieut. Pitcher’s office to settle the preliminaries of my discharge, and was informed that in consequence of the retention of compellation of the Regiment, and its present size he could not yet muster me out, and that I would have to remain at least until the expiration of my term. This was quite a disappointment, but-“One truth is clear, whatever is, is right.

By March 1865 he records his farewell letters to his fellow doctors and military superiors. He makes no entries until June 1865, no comment on Lee’s surrender or the end of the war, not any remark on Lincoln’s assassination.

Spiritualism. Entries of the 14th June 1865 again break away from the mundane to reveal another undercurrent of his thoughts, Spiritualism:

My mind has been crowded by fancies concerning these beings. Are there indeed such beings? Is this space between us and the Deity filled up by innumerable orders of spiritual beings. . .?”

. . .They attend the redeemed; they wait on their steps, they sustain them in trial; they accompany them when departing to heaven.

The first quote is attributed to the author Washington Irving. The belief that one could communicate with the dead, was very strong as a result of the horrors of the Civil War. One of the most famous of the spiritualist believers was Mary Todd Lincoln. As a witness to various forms of death, Dr. Willard also looked for answers.

The Pawnee Murders. A year later in Springfield, Illinois where Dr. Willard has relocated with his family we find another entry concerning the fate of two men convicted of murder and sentenced to be hung.

Who supposes that fear of death upon the gibbet so overawes the turbulent and unruly passion of wicked men as to restrain them from the commission of crime? Who believes that physical suffering by strangulation constitutes ample expiation for a deed of blood? . . . If the death penalty were a sovereign antidote to crime, and the guilty murderer the heinous of criminals, there could be none with pitying interposition to obstruct it execution; . . .let justice not bear the semblance of revenge; let not the purity of Heaven be sullied with the guile of earth; let the daughter of the skies, even in the cell of the repentant murderer, meet and kiss her sister, Mercy.

Equality and the Negro. Again on June 6th 1866, Dr. Willard copied another letter which he wrote to his cousin, the Reverend George Washington Willard in Frederick County, Maryland:

. . .This rubbing and scrubbing of the Negro to make him white is all fal-de-rah. The man is neither white nor black! Do we not know that the body is only the instrument of the immortal part, the soul, and that that constitutes and contains all that is noble in man. Time and circumstances have thoroughly tested the value of our institutions. For their preservation and perpetuation we have been adjured by that illustrious man, whose honored name you bear (George Washington) to look neither to white skins nor wooly heads but “to the virtue and intelligence of the people”. These are the high qualities that ennoble mankind, and from which springs the righteousness which exalts a nation . . .

The Prodigal Son. Dr. Willard was the father of three sons and three daughter: Sarah Ellen, James T., Mary Anna, Daniel, Edwin, and Eliza Carrie. Of the sons, Edwin appears to have been the renegade of family. Dr. Willard records a letter he received from Edward, written on September 6th 1871 from Cumberland, Maryland with his brother Daniel.

Dear ma, . . .don’t get uneasy about me dear Ma. I am all right inspite of George Tomson can say or do. And I all these reports be true about me in danger know that I am secure here from arrest. . . .I suppose Dan told you all about me. I know he did. His big mouth would decay if his Basso did not blow up mischief. So you see and hear all this news. He won’t give me any satisfaction about things in Cumberland.

. . .My days are nearly over. I was not born in the woods to be scared by an owl to hoot neither am I scared by the dangers that hovers near. I have been here now ten weeks. . .If they chase me I will light out to the mountains and now remember my dearest Ma if you should not hear from me don’t get uneasy-I will be making my way back through the South and come out in Virginia someplace. . . .

There is no commentary to this letter, the only one not written to Dr. Willard. Edwin’s fate is uncertain. On February 6th 1887 Dr. Willard included the following information in a letter to his brother-in-law Elie Kriegh, Esquire in Springfield, Illinois: James is in Philadelphia; Edwin is presumed to be in Calcutta, India; Daniel and “the girls” are at home in Lovettsville and Eliza (his sister) is also living with them in Lovettsville.

Hopefully, these snapshots of James Willard’s journals inspire our readers to look into their own story, recorded in letters and journals tucked away long ago. If you are a Willard descendant (and there are many) and you have documents, journals, letters and pictures that are part of James Willard’s story, the Lovettsville Historical Society would be very interested in seeing them or making copies. Also, if you have documents pertaining to James Willard’s cousin, Wilfred E. Cutshaw, please contact us at our email or Facebook address.

1. Dr. James Willard as quoted in Willard Memoir: Life and Times of Major Simon Willard by Joseph Willard, Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1848, Boston.