James Rada was scheduled to be our speaker for the May 17 presentation in our monthly Lecture Series — which is now on hold due to the Coronavirus shutdown of public events. We asked Mr. Rada if he would submit something we could publish in our newsletter, and he kindly provided us with a chapter from his book Secrets of Catoctin Mountain: Little known stories and hidden history in Frederick and Loudoun Counties, published in 2017. Here is the chapter:

The Great Calico Raid

by James Rada

By 1864, the tides of war had shifted to favor the Union. However, the rebels weren’t beaten yet. Although Union Gen. Ulysses Grant had Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee pinned down around Richmond and Petersburg, Lee sent Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Second Corps to help defend the Shenandoah Valley.

On June 18, he defeated Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter at Lynchburg. This left him with a clear path to the Potomac River. He began moving his 20,000 men north.

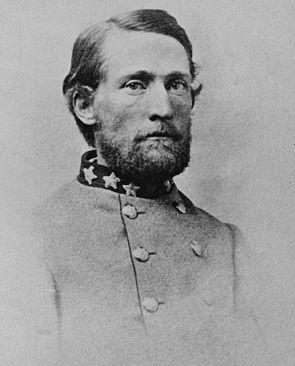

Col. John Mosby and his Confederate Rangers began raiding Maryland communities along the river to screen Early’s advance.

“Although he never admitted it, Mosby clearly sought to ride Early’s coat tails in an attempt to enhance his reputation and his transformation into a member of Virginia’s elite,” Arnold M. Pavlovsky wrote in In Pursuit of a Phantom: John Singleton Mosby’s Civil War.

Rangers were smaller units that cooperated with the Confederate Army but operated independently, moving more quickly in smaller companies.

Mosby’s Rangers left Upperville, Va., on July 3. It was a 100-plus degree day, and the ground was dry, which made it a dusty, unpleasant ride to Bloomfield, Va., for the 250 Rangers and their four howitzers.

During their ride north, Mosby had his men spread a disinformation campaign. Northern Loudoun County was pro-Union, so Mosby instructed his men to answer any questions about who they were and what they were doing to say that they were an advance guard of Longstreet’s Corps.

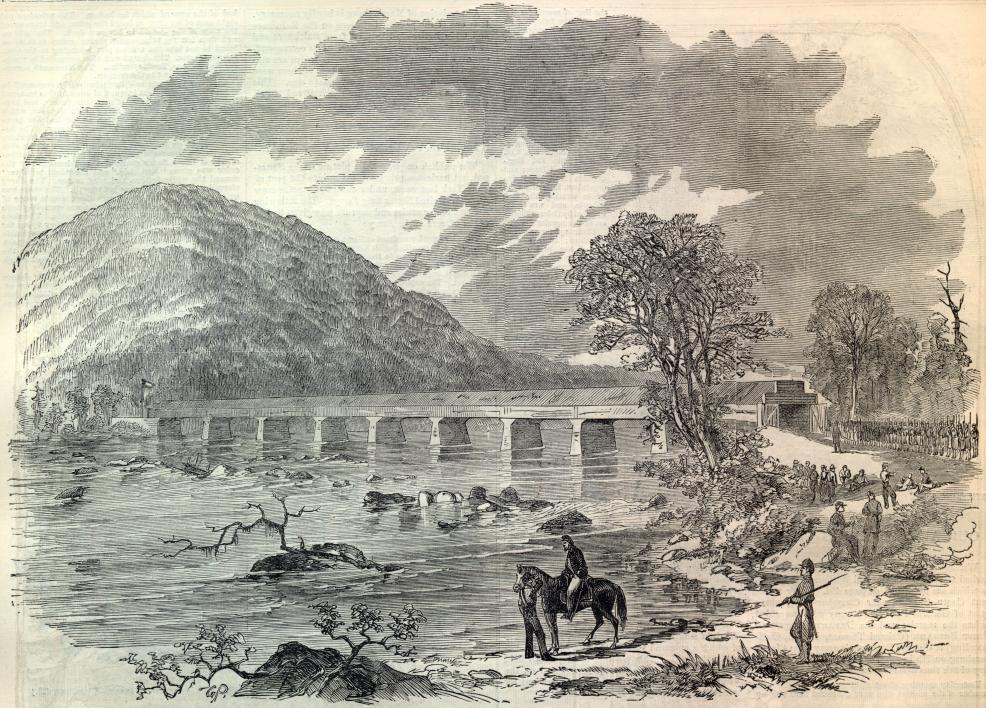

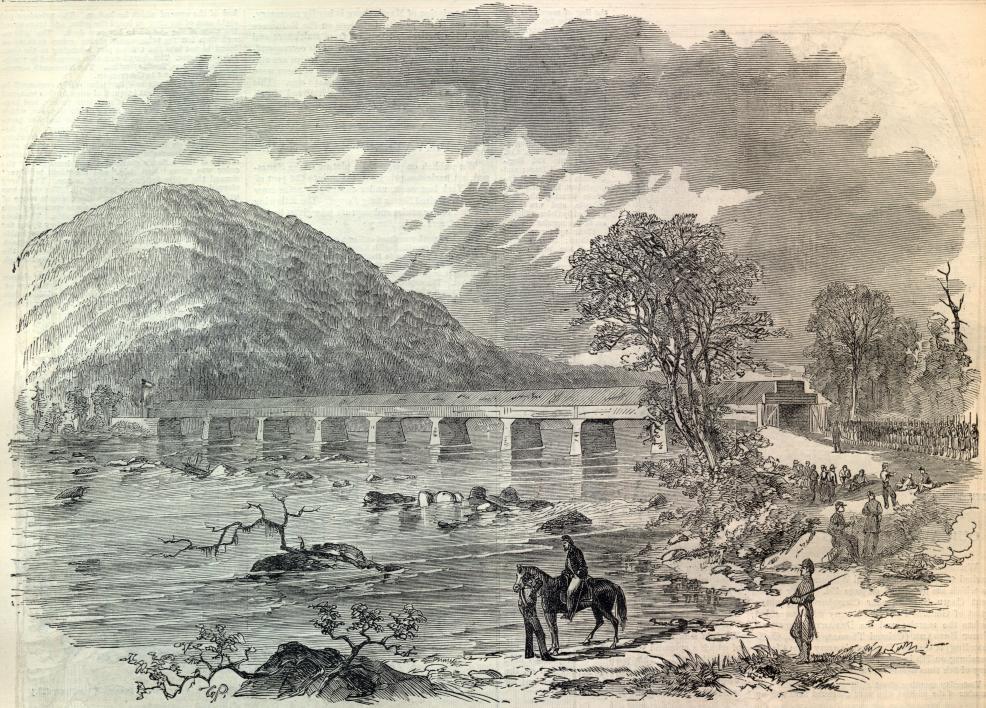

They arrived at the Potomac River the next day. Scouts reported that Union soldiers were in Point of Rocks and a picket was on Patton Island in the river. Mosby examined the situation himself and discovered that the Union soldiers were members of the Loudoun Rangers, a Union Ranger unit formed in Loudoun County. They were manning a small earthwork overlooking the river.

Mosby had one of cannon fire on the island. He wrote later, “As this was the first occasion on which I had used artillery, the magnitude of the invasion was greatly exaggerated by the fears of the enemy, and panic … spread through their territory.”

Two dozen sharpshooters under the command of Lt. Albert Wren aided the cannon fire. They provided cover fire as the Rangers began swimming their horses across the river.

Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson had burned the bridge on June 9, 1861, to try and keep Union troops from crossing into Loudoun County.

Under fire, and facing the approaching Rangers, the Union soldiers fled the village, heading toward Frederick.

Once the Rangers reached the Maryland shore, they faced another obstacle. They still had to get their men and horses across the six-foot-deep C&O Canal. A permanent bridge spanned the canal near Lock 28, but the Union soldiers had removed the planks from it. Mosby’s men had to rip boards from an old warehouse to make temporary flooring for the bridge so the men could cross into town.

“Most of the men went into the dry-goods business, and soon four regular shops and one sutler’s establishment were emptied of their contents,” Maj. John Scott of the Rangers wrote in his memoir.

One shopkeeper, Louis Meems, told Mosby that he was a southerner. The Rangers returned his goods.

The men also took cigars, food, and liquor from a canal boat that had the misfortune of being near Point of Rocks at the wrong time. Telegraph wires were cut and logs laid across the railroad tracks.

When a train approached the village from Harpers Ferry, the howitzers began shelling it. The engineer managed to get the train in reverse and escape. However, the Rangers knew the Union army would soon know of the situation in town.

The men burned the Union camps and then retreated across the river. “Finally having filled up their sacks with loot, the Rangers swam their horses across the river and returned to Virginia. Some of the men were wearing bonnets and carrying large bolts of cloth,” Pavlovsky wrote.

They traveled down the Carolina Road until they found a place to make camp. Maj. Scott wrote, “As they passed along the road, some arrayed in crinoline, some wearing bonnets, and all disguised with some incongruous and fantastic article of apparel, they looked like a company of masqueraders.”

This led to the skirmish being called “The Great Calico Raid.”

That evening, the Rangers celebrated by drinking confiscated whiskey and eating pound cake that had been found in a Union officer’s tent, according to Pavlovsky.

The next day, Mosby sent three wagonloads of the captured goods along with 100 men to Fauquier County.

* * * * *

Another account of The Great Calico Raid can be found on pages 267-269 of Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia, by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Sounders, which is on sale at the Lovettsville Museum.