By Edward Spannaus

[Updated December 17. 2023]

(This is one of an occasional series of articles concerning the impact of the American Revolution on the Lovettsville area, formerly known as “the German Settlement.” The first article in this series was about Virginia’s Religious Freedom Law and the Lovettsville churches, which was published in our October newsletter and can be found here on our website. The present article, and others to follow, will look at the feudal land-holding practices in this area which were abolished by the American Revolution.)

People coming into the Lovettsville Museum often ask: “Who was Lovett?” Our answer is generally that he was a land speculator who never lived here.

But David Lovett was a piker compared to the real land speculators and absentee landlords who previously owned the land on which the German Settlement developed. The largest of these were two British noblemen: Thomas the 6th Lord Fairfax, and Charles, the Earl of Tankerville. The latter owned almost the entire eastern half of the German Settlement before, and even for some years after, the Revolutionary War.

My interest in this was aroused during my research into the lives of settlers in the German Settlement, and in particular Revolutionary War Patriots. I was struck by the fact that most of the Germans did not actually own the land that they farmed until well after the Revolutionary War; most don’t appear in the County land records at all until after the Revolution. The year 1793 jumps out as the year in which a number of the German settlers were finally able to purchase the land on which they had lived and farmed for many years or even decades. Notably, this was ten years after the end of the Revolutionary War.

The explanation often given for this, is that the Germans who came here from Pennsylvania were just “squatters” who were tolerated by the big landowners because they were good farmers and improved the land. That seems to be true, but it’s not a complete explanation.

To understand not just why the German settlers didn’t buy land, but why they couldn’t buy land, we have to start with the British manorial system of landholding which dominated Virginia and other colonies.

The Manorial System

In feudal England, land was the basis of wealth and social standing. The nobility owned the land (at the suffrance of the monarch, of course), collecting annual quitrents, and commoners had no possibility of ever possessing the land on which they lived and labored. (You know something about how that social system and its rigid class stratification worked, if you’ve watched films based on Jane Austen novels, or the knock-off series Bridgerton and related British dramas. The common story line is the desperate struggle to keep the country estate in the family and be able to pass it down through the generations.)

In the North American colonies, all the land technically belonged to the King, or Queen, and it was granted to the colonial officials through proprietorships or through charters. In northern Virginia, we have a clear case of this, where the five million acres of the “Northern Neck” – the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers – was granted by Charles II in 1649 to a syndicate centered on the Culpeper family. Through marriage and other devices, this vast territory was consolidated in the hands of Thomas Culpeper, the Fifth Lord Fairfax. His son, Thomas, the Sixth Lord Fairfax, inherited the land as a single tract, and he managed and controlled it until his death in 1782.

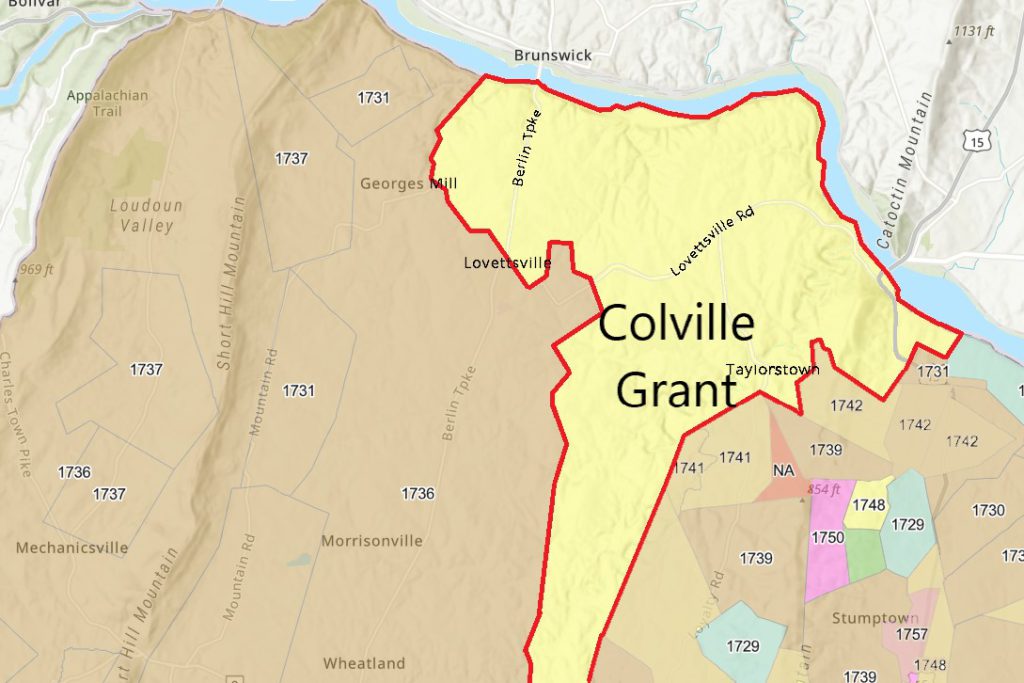

From time to time, Thomas sold or granted large chunks of the Fairfax Proprietary to various land speculators. One of these was a merchant and sometimes mariner named John Colville, who acquired various large parcels of land directly or indirectly. The tract that concerns us constituted the eastern half of the German settlement, which was acquired by Colville in 1742. It stretched from Dutchman’s Creek and the north side of what is now Lovettsville’s Broad Way, to almost everything east of Milltown Road to the Catoctin Mountains.

The Earl of Tankerville was Colville’s biggest creditor (they were related through marriage), and when Colville died in 1756, Tankerville was given large amount of land in Virginia and Maryland, and a large number of slaves, in satisfaction of Colville’s debts. He thus became one of the largest landowners in northern Virginia – although there is no indication that this nobleman from the north of England had any previous interest in the American colonies — and he is therefore of interest to us, since a large chunk of his landholdings were in the German Settlement, in what became Loudoun County in 1757.

Who was (or were) the Earls of Tankerville?

First of all, their name was Bennett (or Bennet). The “Earl of Tankerville” was a noble title bestowed upon Charles Bennett, the 2nd Baron Ossulton, in 1714. (An Earl is a higher rank than Baron). He was the father of another Charles Bennett (1716-1767), the 3rd Earl of Tankerville, who was the one who acquired lands in Loudoun County from John Colville. Charles the 3rd Earl was also a Knight of the Most Ancient and Noble Order of the Thistle, and was one of the “Gentlemen of the Bedchamber” to the Prince of Wales.[i]

Charles, who like the rest of his family never set foot in America, controlled his approximately 16,000 acres of land in northern Loudoun County through an agent, John Patterson. In March of 1759, Charles went before the Lord Mayor of London and designated Patterson to depart from England within six weeks for Virginia and take possession and management of Tankerville’s new lands as his agent and manager. Patterson arrived in Leesburg in 1760, and in 1761 he purchased a house and lot (Lot No. 11) on Loudoun Street just east of King Street in Leesburg, to set up his Land Office.

Colville’s “Catoctin Tract” now became known as “Catoctin Manor.” During the period 1760 to 1763, Patterson only executed formal leases for 13 parcels of land, in the range of 100 acres each.[ii] These were in the form of a long-term “lease for lives,” a feudal mechanism by which land was leased for the duration of the lives of three specified family members, such as the lessee, his wife, and a son; or the lessee, his son, and a daughter.[iii]

These leases amounted to a total of only about 1400 acres, out of more than 16,000. What was he doing with the rest? Much of it was being farmed by German settlers from Pennsylvania, who for the most part lived and labored at the pleasure of the landowner. As low-born and as aliens, they were not regarded as being entitled to buy the land, or even to have the protection of a formal lease. They could be thrown off at the whim of the absentee landlord, and it doesn’t appear that there was anything they could do about it.

In fact, these German farmers were the vast majority of those living and farming on Tankerville’s land. As we will see in a later article, when the Tankerville family sold off their holdings in the 1790s, of about 100 transactions over three-fourths of these were to German-named individuals.

[slideshow_deploy id=’5977′]

Charles, the 3rd Earl of Tankerville, died in 1767. In his Will he left his landed property in America to his two sons, Charles, the 4th Earl of Tankerville, and Henry Astley Bennett. They held on tightly to the family property: I found no land transactions from 1763 until 1789. The late Robert Constantino, in his three-volume Colonial Catoctin work, published in 2006, says there were no further transactions by the Earls of Tankerville and their agents, after the 1760s until the late 1780s. For reasons we shall see, during the Revolution and for a number of years thereafter, there was great uncertainty about land owned by “aliens,” (non-citizens of the new United States, particularly British subjects), and this may account for the lack of any sales, or even recorded leases, of the Tankerville lands.

Last Will and Testament

The Thomas Balch Library has in its possession a hand-written copy of the Last Will and Testament of Charles Bennett, the 3rd Earl of Tankerville – apparently the only such copy existing in Virginia. This document, signed by Tankerville in 1762, is of interest in that it sheds some light on the customs and mind-set of the English nobility at that time.

This Will, along with the 1756 Will of John Colville, continued to be cited up through the 1790s, often at great length, in leases and deeds executed by Tankerville and his attorneys.

Tankerville specifies that he is to be buried “without pomp,” and that any arrears of rents which were owed to him, are to be collected with all convenient speed.

His wife, Alicia Astley, “the Right Honorable Dowager of Tankerville,” is to be provided with 500 Pounds (Sterling), jewels, a plate marked with the Ossulton Arms, china, and household goods (but not those from Chillingham Castle which were to go to his son Charles of Ossulton).[iv] His wife was also to be provided with coaches, carriages, and coach horses, as well as his two organs, musical instruments, and books. His son Charles is to provide his mother with a monthly annuity, “enabling her to live in a house proper for her Station and Quality.”

Tankerville’s Will then cites property to which he (Tankerville) is entitled, under the earlier Will of John Colville, who is identified as being of England and of Fairfax County in Virginia. Tankerville specifies that he is entitled to “diverse Plantation Lands, horses, utensils, Negroes and Stock” belonging to those various Estates, and a 2/9 share of a copper mine and 200 acres of land at Difficult Run in Fairfax County, and that this property is to go to his son “Charles Lord Ossulton.” All other Colville lands were to go to his other son Henry Astley Bennett for the term of his natural life, and after his death, these lands were to go to “the heirs of his body, to take as “tenants in common, not as joint tenants.”[v] But if Henry were to die “without issue (i.e. childless, which probably meant “without male issue”), then his portion would revert to the estate, to then be given to Charles Lord Ossulton. Tankerville also made a provision for his daughter Francis Alicia if she lived to age 20 or married with her mother’s consent; if she married without consent, it seems that she would be cut off.[vi]

You can see how these provisions are designed to keep the land holdings within the family. Another provision in Tankerville’s Will also shows this. If his sons were to sell the lands in Virginia and Maryland, the proceeds were to be used for the purchases of “lands of inheritance” in England. All in the family.

* * * *

In our next installment, we will look at what happened to the Tankerville (and Fairfax) landholdings during the American Revolution. How did they avoid having their property seized, when Loyalists all over Virginia were seeing their property confiscated? Why was the 4th Earl of Tankerville in correspondence with none other than George Washington? And do we know why the Bennetts sold off much of their land in the 1790s? We will attempt to answer some of these questions next month.

[i] The British Compendium, or, Rudiments of Honor (London: Bettesworth and Hitch, 1731), pp. 495-497. (Accessed through Google Books.)

[ii] In the Loudoun County Deed Books, these 14 transactions begin with a lease to Grant Williams (Deed Book B 342), on 24 June 1760, and end with a lease to William Trammill on 1 May 1763 (Deed Book C 660).

[iii] Of the 13 transactions, only two appear to have been Germans: Teel (Diehl), and Counts (Koonz).

[iv] The family had at least one other house, the Mount Felix Mansion in Walton, a village in Surrey on the Thames, about 15 miles from central London. The Ambulator, or Tour Around London (London: T. Gillet, 1800), p. 225. (Accessed through Google Books.)

[v] The distinction today seems to be that tenants in common can sell their share to anyone, and upon their deaths their property can be conveyed to anyone. When a Joint Tenant dies, their property automatically passed to the other Joint Tenant(s). It may have been different in the 18th century.

[vi] It seems that this is what did happen. According to an online discussion group about the English peerage, “Alicia, Dowager Countess of Tankerville,” left “one shilling each to her `unworthy and undutiful daughters Camilla Elizabeth, widow of Count d’Onhoff (?) and Frances Alicia, wife of Peirson Bouson.’” Her first beneficiary was her “dearly beloved and dutiful” son Henry Astley Bennett.