By Michael Zapf

Readers may recall the article published on the Lovettsville Historical Society website of January 25th, 2018, “The Fascinating Story Behind Wilfred Emory Cutshaw’s Crumbling 1854 Book” which also appeared as “Gems of the Lovettsville Historical Society and Museum-Wilfred Emory Cutshaw.”

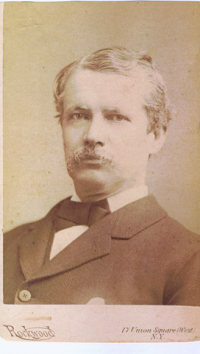

Cutshaw was a Virginia Military Institute graduate (class of 1858) who rose through the ranks as an artillery commander in the Army of the Confederacy, eventually distinguishing himself as the Chief Engineer for the city of Richmond. His lasting legacy are city’s grid, parks, landscapes, reservoirs, armories, schools, fire stations and markets. And yes, in no small way Wilfred Cutshaw is responsible for the statues and monuments of the Confederacy that line Richmond’s Monument Boulevard and are the focus of bitter outrage and controversy today.

Cutshaw’s connections to Lovettsville and the German Settlement are still not entirely clear. However, he shares kinship with a Lovettsville resident of the same era, Dr. James A. Willard, MD, whose residence on Pennsylvania Avenue in Lovettsville was the subject of the Historical Society’s monthly presentation in October 2018. Dr. Willard’s written legacy can also be considered gems of the Lovettsville Historical Society.

Wilfred E. Cutshaw and James A. Willard were cousins, their common ancestor was Elias Willard (1734-1819) a prominent Frederick County, Maryland farmer and descendant of French Huguenots who emigrated among and with the German Palatines in the 18th Century. Elias was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, enlisting in the Maryland Militia, Captain Poe’s Company of the 34th Battalion, as a second Lieutenant.

James Willard was born in 1820 and grew up in Berlin (now Brunswick) and Jefferson, Maryland. He studied at the Hagerstown Academy, Pennsylvania (now Gettysburg) College ,and earned his doctorate in medicine at the University of Maryland. In February 1862, the newly minted, 22-year old doctor joined the 1st Maryland Volunteer Regiment, known also as the Potomac Home Brigade, a pro-Union unit which had been organized in Frederick. His position throughout the war was Assistant Surgeon. The unit was engaged to guard the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, canals and Potomac River crossing from Martinsburg to Point of Rock. The Regiment fought in major battles including the siege of Harpers Ferry, New Market, Winchester, Monacacy and Culps Hill at Gettysburg and sustained losses of 45 men and officers killed or mortally wounded, and 86 from disease.

The Lovettsville Historical Society is privileged to own three ledger journals kept by Dr. Willard. In the earliest ledger Dr. Willard recorded the details of running the military hospital at Harpers Ferry. Entries begin in November 1864 and contain meticulous details of expenditures, supplies on-hand, requisitions of supplies and food, and the number, names and conditions of the sick and wounded in his charge. The ledger also includes verbatim copies of all correspondence sent and received, as well as excerpts from his reading of history, philosophy, theology, literature, and issues of interest.

An example of the quality and depth of his thoughts can be found in the words of a copied letter to his cousin, the Reverend George Washington Willard, dated June 1st, 1866 in response to comments on Negro slavery:

“My dear Washington,

. . . I will ask you if you have ever seen anything enchantingly lovely in slavery as that you could be persuaded to submit yourself to its discipline?

I have known you for twenty years in a region of country where the institution existed and where you saw it in all its forms, but I do not remember at this moment ever to have heard you lament that you were not a slave.…

If you mean by freeing the negro simply to release him from compulsory labor and then leave him exposed to all the ferocity and vindictiveness and cruelty of his late masters, I say seriously and honestly that I do not think it would better his condition; but if you mean to admit him upon the platform of Equality, and let Congress have the management of him for a little while, I say with the same seriousness and honesty, I do think it would better his condition.”

George Washington Willard was a clergyman of the German Reformed Church and had been pastor at the German Reformed Church (now St. James United Church of Christ) in Lovettsville.

There are surprising silences in these journals as well. Dr. Willard does not record any personal correspondence with his wife or children. There are no reports or comments on military operations. He writes in anticipation of the end of the war so that he can be discharged and resume practicing medicine as a civilian. When the war ends in April 1865, he notes it without fanfare. He never records the news of or his thoughts about President Lincoln’s assassination.

In the period following his discharge, he records his plans, frustrations, and failure to establish himself and his family in Springfield, Illinois. For Dr. Willard, the period from late 1865 until 1867 is a period of frustration, failure, bitterness, bankruptcy, and finally despair: This is expressed in a letter to his brother-in-law, the Rev. Philip Willard, written from Springfield, Ill., on June 22nd, 1867. (Rev. Willard, who had been pastor at New Jerusalem Lutheran Church in Lovettsville in the late 1840s, had gone on to become a prominent church official in Pennsylvania.)

In this letter, Dr. Willard is at the end of his tether. He has been unable to establish a practice, and is in debt. Other option for making a living (selling subscriptions for books, or farming) are insufficient or beyond his means. Besides his wife, Susanna, James was the father of three sons and three daughters.

“Sir,

If from the abysses of wretchedness and misfortune you have never reached, you will listen for one moment to a voice which once perhaps was entitled to some consideration—hearken.

There are those here for whom your heart still feels a brother’s tenderness; and others who for a dear sister’s sake will move your softest sympathies; these, all have been brought to degradation, want, temporal ruin by what some esteem the perverse folly and persistent wickedness of the man, who owns himself their natural protection. From this state of abject suffering he can see no possible method of extraction or hope of better things to come. For himself he has nothing to say, nothing to ask, nothing to expect of Christian charity . . . let him pass.

For those whom he must not be thought even most remotely deserved to repudiate as wife and children, although an adverse [illegible] may place between them a bar of separation, for them who have not erred from the faith you hold and preach, be your bonds of compassion moved, your deeds of love be shown. Help Nannie if you can out of this den of thieves and miscreants to some humble home where she can rear her children in the love of truth, virtue, tenderness, honesty and where in the consistent exercise of her duties . . .they may earn shelter, food and raiment fit and sufficient for their daily comfort and their daily need. That is the voice, do you hear it?”

The letter likely shocked Philip Willard into helping; it is difficult to read the very faint entries in the journal for this period. But not many months later, the journal records his efforts to reestablish himself again back East in Maryland, and finally in Lovettsville. Entries from Lovettsville show promissory notes, a verbatim copy of the deed of the house on Pennsylvania Avenue, letters of advice to his two grown sons, and their letters to him. The accounts of his patients in Lovettsville — both “colored” and white – are recorded.

James Willard’s journals are more than documentation of accounts due and owed, more than an inventory of equipment and people; they contain and encapsulate the character of a man at a time of great national transition, in his own words on subjects that were meaningful to him. Dr. Willard died on  July 30th, 1906 at his home on Pennsylvania Avenue (pictured at left) and is buried at the Union Cemetery in Lovettsville.

July 30th, 1906 at his home on Pennsylvania Avenue (pictured at left) and is buried at the Union Cemetery in Lovettsville.

The Lovettsville Historical Society has undertaken to digitally scan, enhance and transcribe the Willard journals.