By Lori Hinterleiter Kimball

Anyone walking or driving recently by the intersection of East Broad Way/Milltown Road and Lovettsville Road would have noticed earth-moving equipment contouring the land in preparation for our new community park. We will have ballfields, trails, and other modern amenities. This new addition to our town encompasses land that was farmed for over 200 years and contains nine historic buildings in various stages of neglect, and the remains of at least three.

Loudoun County, with substantial aid from the Town of Lovettsville, purchased 90 acres in 2004 for the creation of a park, but our story starts over 200 years ago with Christian Gottlieb Ruse, who was born in 1745 and moved to Lovettsville and was farming by 1769. He leased land, as was the practice at the time, then purchased 185 acres in 1803.

Ruse enslaved at least one person during his lifetime. The 1820 Federal Census listed him as enslaving one female between the ages of 14 and 26. Christian died in October 1821 and is buried in the New Jerusalem Church Cemetery next to his wife, Catherine, who died in 1802. In his will, Christian bequeathed “negro girl Mary” to his son Henry for the length of Henry’s life.

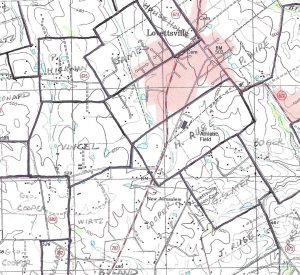

Christian also gave his son Henry a 2/3 interest in the 185-acre farm, and Henry eventually bought his brother Frederick’s 1/3 interest.[1] The map at the left shows the property boundaries as of 1860 for the Ruse farm.[2] It was bounded on the east by present day Broad Way/Milltown Road and extended diagonally southwest across today’s Berlin Turnpike at its intersections with Lutheran Church Road and South Loudoun Street. The elementary school was eventually built on a portion of the former Ruse farm.

Christian also gave his son Henry a 2/3 interest in the 185-acre farm, and Henry eventually bought his brother Frederick’s 1/3 interest.[1] The map at the left shows the property boundaries as of 1860 for the Ruse farm.[2] It was bounded on the east by present day Broad Way/Milltown Road and extended diagonally southwest across today’s Berlin Turnpike at its intersections with Lutheran Church Road and South Loudoun Street. The elementary school was eventually built on a portion of the former Ruse farm.

Henry was a farmer, raising cattle, hogs, and milk cows and growing wheat, potatoes, and corn. One enslaved girl was recorded in the 1840 Census for Henry Ruse. She was under the age of 10 and probably worked in a domestic capacity. In the 1860 Slave Schedule, a man over the age of 50 was recorded. Henry hired him out to Jacob Virts. That census also recorded the number of slave dwellings on a property, and Henry was listed with one slave dwelling on his farm.

In 1852, the Loudoun and Berlin Turnpike Company laid out a route for its roadbed and assessed $150 in compensation to Ruse for cutting a 40′ wide swath through his land.[3] As can be seen in the 1860 map above, the road divided many farms and later would become a boundary as farmers like the Ruses divided their land into smaller parcels.

Henry died in 1868 and was buried in the New Jerusalem Church Cemetery, and the farm descended to his wife Sarah, daughter Susan, and two sons, Emanuel and Joseph. Emanuel inherited 60 acres on the northeast portion of the farm, and there were no buildings on it.[4] His sister Susan inherited the 54-acre home farm on the southeast.[5] Joseph inherited 56 acres that spanned the Berlin Turnpike.[6] The cluster of historic buildings on today’s park site are on the land that Emanuel inherited, indicating they were constructed or moved there after 1868.

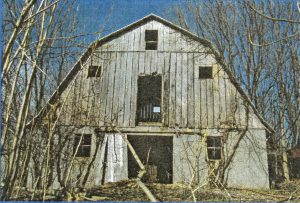

Emanuel also owned a house and lot in the town of Lovettsville.[7] He was a carpenter and had a shop there. By the 1880s, this house was his main dwelling, and his daughter S. Anne and her husband Winfield S. Seitz lived on the 60-acre property Emanuel had inherited from his father. In 1885, Seitz constructed a bank barn made of timber on a stone foundation. It was approximately 33′ wide x 44’long, and it had a slate roof.

The parcels owned by Emanuel and Susan were eventually purchased by the Smiths[8] and brought back together in 1905 when H.M. and Bertie Cooper purchased them.[9] The 112-acre tract was purchased by Owen Reed in 1933,[10] and it is from a portion of this parcel that today’s 90-acre park is being developed.

The Reeds continued to farm the property and transitioned to dairy farming, as did much of Loudoun County during the late 1800s through mid-1900s. In 1952, the Reeds constructed a large dairy barn (pictured at right) and adjacent milking parlor.

The Reeds continued to farm the property and transitioned to dairy farming, as did much of Loudoun County during the late 1800s through mid-1900s. In 1952, the Reeds constructed a large dairy barn (pictured at right) and adjacent milking parlor.

The Ruse/Reed Historic Buildings

The southern section of the park, where most of the earth contouring has been taking place, is slated for active recreation, such as ball fields. The northern section is designated for passive recreation, such as walking trails and community garden beds. This is the area that contains the historic buildings from the Ruse and Reed eras.

The cluster of domestic and agricultural buildings includes a farmhouse, summer kitchen, spring house, a meat house, chicken house, machine shed, animal shed, and dairy barn, and the remains of an icehouse, silage pit, and a stone bank barn that was vandalized and burned in the 1980s.[11]

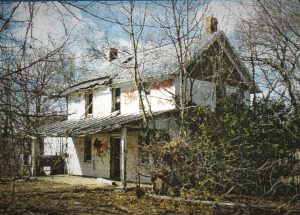

The dilapidated farmhouse that we see today along the walking path between the community center and elementary school was built in at least two stages. The original section of the house is two stories, measures 27′ x 18′, and is built of logs. It is a sizable structure for that method of construction. The 12′ x 16′ addition is wood frame with Victorian features such as fish scale shingles and high gabled roofline. It was probably built by the Ruses or Smiths in the late 1800s.

The 8′ x 12′ meat house (at right) is of log construction and, according to a Reed family member, was moved from the southern part of the property to its current location.

The 8′ x 12′ meat house (at right) is of log construction and, according to a Reed family member, was moved from the southern part of the property to its current location.

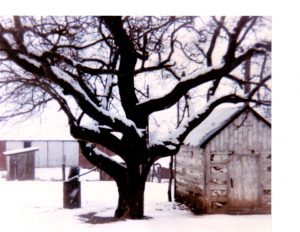

An archaeological study was done in 2009, predominantly on the southern section of the parcel that was slated for extensive land disturbance during the park’s construction. The archaeologists identified evidence of at least one building in this area near an old black walnut tree. Portions of two stone and brick foundations were uncovered with “a wide scatter of historic materials over approximately an acre.”[12]

A 12′ x 16′ two-story timber frame building, noted in documents as the summer kitchen, contains a large stone fireplace for cooking and has a second floor accessed by a winder staircase.

The springhouse is located to the northwest of the farmhouse along a small stream. Made of rough sawn lumber, it retains the inlet for the stream water to cool the foods that were once stored inside.

From the late 1800s to the mid-1900s, dairy farms were prominent in Loudoun County. The growing demand for milk and butter in Washington D.C., coupled with nearby railroad transportation, led to a shift in grain and livestock farming to dairying. The large dairy barn was built in 1952 by the Reed family. The main level still contains evidence of the milking parlor and calf birthing room. The second floor was used for storing hay and grain and was accessed through a large exterior door. The numerous windows in the structure were designed not just for light but to provide ventilation and healthy air flow.

The large bank barn that Seitz constructed in 1885 remained until the 1980s, when it was vandalized and destroyed by fire. The remains of the stone foundation are still evident amidst the cluster of buildings.

Was one of these buildings the slave dwelling?

The short answer is, “probably not.” The summer kitchen has the architectural style of a living and working space for one or two enslaved people or family. It was close to the main house; it has a fireplace for cooking and heat; and it has a second story that could have been used for sleeping. However, the historic record indicates none of the buildings at the current park site were there before 1868. It is mortise and tenon construction but contains wire nails, which did not come into widespread use until the late 1800s. Could it have been moved there from the earlier Ruse homestead?

A more likely location of the original slave dwelling is on the southern section of the property where the stone and brick foundations were found during the archaeological study. More research and analysis are needed at both locations to try and learn more. In fact, County Archaeologist Michael Clem noted that the southern location had enough artifacts and features to make it “potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places for its potential to reveal valuable information concerning the lifeways of early Lovettsville settlers.”

What Comes Next?

When the County acquired the property 16 years ago, a committee of local residents and park staff met regularly to plan for the park’s features. The County intended to restore the historic buildings and use them, among other things, for interpreting farm life and farming on a rural Lovettsville property.[13]

Years went by before funds were allocated to start construction of the park. A chain link fence was installed around the historic buildings, but it did not prevent vandals from entering. Graffiti and damage are everywhere. Lack of funds and maintenance have caused the buildings to fall into disrepair.

The County’s current plans are to demolish the farmhouse and dairy barn, but leave the foundations so they can be used for interpretation. The County will salvage some logs from the earliest part of the house. The concrete pad of the dairy barn is projected to hold a picnic pavilion. Local citizens have asked the County to professionally document the farmhouse and two outbuildings, with the goals of identifying construction dates and techniques, and to learn more about the evolution of the farm from possibly pre-Civil War to 1950s dairying.

The archaeological site by the old black walnut tree has not been disturbed, and citizens have asked that more analysis be done. One goal should be studying this area and the farmstead site to see if the former slave dwelling can be located.

The Lovettsville Historical Society would like to hear your comments about the proposed plans for the historic buildings, as well as information or remembrances about the Ruse, Smith, and Reed families; the historic buildings; the Reed dairy business; and/or the land that is becoming our Community Park. Please contact the Lovettsville Historical Society at info@lovettsvillehistoricalsociety.org.

Lori Hinterleiter Kimball is a historical researcher whose projects cover various topics in Loudoun’s history. She is a member of the Lovettsville Historical Society; has served on the boards of several non-profits; is a member of the Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library; and serves on the County’s Heritage Commission. Lori was previously the Director of Programming and Education at Oatlands, and is now the Executive Director at the Loudoun Heritage Farm Museum in Sterling.

Notes:

[1] Loudoun County Will Book N:360 and Deed Book 3Q:173.

[2] Local historian Wynne Saffer mapped properties in Loudoun County as of 1860. He overlayed the parcel boundaries on modern USGS maps.

[3] Loudoun County Deed Book 5F:229.

[4] Loudoun County Chancery Cause 1908-015 (formerly M4770). This lawsuit, started in 1895, was to determine the expenses incurred for constructing the 1885 bank barn. A witness in the cause testified that no buildings existed on Emanuel Ruse’s 60 acres when he inherited the land.

[5] Loudoun County Deed Book 7G:52.

[6] Loudoun County Deed Book 6I:19.

[7] Loudoun County Deed Books 5O:374 and 5V:53.

[8] Loudoun County Deed Books 6S:432 and 7L:349.

[9] Loudoun County Deed Book 9M:468.

[10] Loudoun County Deed Book 10M:477.

[11] Most of the information about the buildings is from Tom Bullock’s valuable reports “Lovettsville Park: Village and Patent Farm Concepts, Circa 1765 to 1900” and “Lovettsville Park: Deed and Title Search”, both circa 2006 and available at the Lovettsville Historical Society and Museum. Tom’s thorough research provided a baseline for the construction and condition of the buildings, and his platting of the property as it changed owners was a very helpful visual (and saved the author a lot of time).

[12] A Phase I Cultural Resources Survey of the Lovettsville Park Property, Loudoun County, Virginia by Michael Clem, Loudoun County Archaeologist, Department of Building and Development. November 2009.

[13] https://www.loudoun.gov/DocumentCenter/View/30419/Item-07–SPEX-2007-0004—CMPT-2008-0006—Lovett?bidId=