By Nancy Spannaus*

Western Loudoun was provided with a treat this week, in the form of a series of book talks by former Loudoun resident and author Linda H. Sittig. Sittig gave talks at the Balch and Purcellville Libraries to overflow crowds on her latest book, entitled Opening Closed Doors: The Story of Josie Murray.

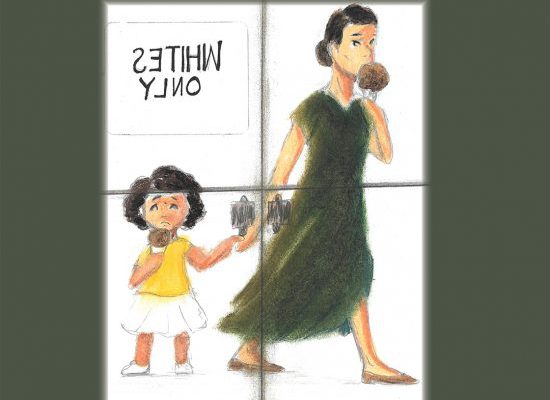

In her June 26 talk at the Purcellville library, which I attended, Sittig presented the story on which her children’s book is based: How the courage of the African American seamstress Josie Murray of Purcellville forced the desegregation of Loudoun County’s library system. Prior to Murray’s challenge, taken in 1956-57, there were very few libraries in the state which were open to both white and black patrons; most African Americans couldn’t access a library at all.

During her lively presentation, Sittig frequently referenced her motivation for writing this story: her determination that children throughout Virginia (and elsewhere) become aware of the fight waged to open libraries to all, and that they use that awareness to make ever more advances toward equity and justice for all people.

Opening Closed Doors: The Story of Josie Murray is available on Amazon, or through the online bookstore Second Chapter Books, which can be reached at secondchapterbks@gmail.com. But let’s briefly review the story here, as Sittig described it.

Josie Takes a Stand

Josie Murray was a seamstress, a renowned seamstress. Her reputation for excellence led her to receive jobs throughout Northern Virginia and even from women in Washington, D.C. Her business was established in Purcellville in a shop she shared with her husband, Sam Murray, an upholsterer.

One day in December 1956, Josie received a request from a Mrs. Moore, who hailed from D.C., to produce a set of Austrian drapes. Josie had no idea what these drapes were; she had never made them before. But when she told Mrs. Moore that, Mrs. Moore told her she could find the pattern in the local Purcellville Library.

Josie had never been to the library; it had an official policy of only serving white patrons. But upon consultation with her husband, and with him at her side, she decided to try to borrow the book with the pattern. When she arrived at the library, Sittig explained, one can imagine her steeling herself for what might be a confrontation. And a confrontation it was.

The librarian immediately accosted her, telling her she could not come in. When Josie insisted that she just wanted to borrow the book with the pattern, the librarian held firm. Finally, she told Josie and Sam that they should call Mr. Emerick, who was both Superintendent of the Loudoun Public Schools and on the Purcellville Library Board. Sam made the call, and Mr. Emerick responded by saying that he would take the book out of the library for Josie. When presented with this offer, Josie said “no.” Faced with the library’s intransigence, Josie and Sam left.

When Josie called Mrs. Moore to tell her that she could not fulfill the contract, and why, Mrs. Moore determined to do something about the situation herself. I’ll call my brother-in-law, she told Josie. Who is he, Josie asked. Dwight D. Eisenhower, President of the United States, Mrs. Moore replied.

After consulting with the President, Mrs. Moore recommended that Josie take legal action. As you might expect, however, no lawyer in Loudoun County would take the case. Once again, Mrs. Moore provided a solution: she informed Josie that Washington, D.C. lawyer Oliver E. Stone, who was famous for representing conscientious objectors, had agreed to take her case pro bono.

In doing his research for the case, Stone hit upon a crucial fact: The Purcellville Library had previously received funds from the Federal government to aid its operations. Hence, he argued, the library was a public institution, and by the rulings of the Supreme Court, had to be non-discriminatory as to race.

However, there was no reasoning with the Purcellville Library Board. Each time the issue of desegregating the library came up, the vote was a stalemate, four to four. As the months went by, Stone hit upon a new tactic: he placed newspaper articles in the press all along the East Coast describing the discrimination in the Loudoun County Library system. Soon, millions of people had heard about Purcellville and its treatment of its black citizens – and this was bad news for Loudoun County’s reputation.

Finally, in April of 1957, the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors issued an ultimatum to the Purcellville Library Board of Trustees, threatening to pull its funding. That worked. The next time the issue came up for a vote, two of the Trustees changed their votes, and the Purcellville Library desegregated.

More about Josie

Ultimately, then, Josie Murray did get to sew the Austrian drapes for Mrs. Moore. But not only that! In the aftermath of the case, Josie was invited by President Eisenhower himself to sew drapes for his farm home in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. (They are still there.) In addition, she got a commission to sew the drapes for the Blue Room of the White House.

Josie’s niece, Linda Jackson King, added some of her own reminiscences about her aunt at the Purcellville event. Josie was a quiet, but strong-willed woman, she said. She would have been very happy to have her story told as Linda Sittig has done.

It took courage for the Murrays to brave the opposition from their neighbors to their demand for equal access to the library system. Linda King, still a child, was with her aunt and uncle and their son during some frightening experiences. One night, some angry citizens staged a 12-car caravan, horns blaring and lights on, which drove back and forth in front of the Murray home. The leader of the pack was no lesser a personality than the county sheriff! Linda King recounted how Sam Murray counseled the children to sit still in the corner, and not show themselves in front of the window. They waited the harassers out, with quiet dignity and undoubtedly a good deal of fear.

Linda King added more personal touches to the story, by showing the audience the small Singer sewing machine that Josie worked on, and a sample of an Austrian drape.

In the question-and-answer period, Linda Sittig emphasized again her resolve to get this story into the school libraries in Loudoun and beyond. She doesn’t expect it to be easy. It took her six years to get a publisher for her children’s book on this subject; publishers claimed such an old story about the small town of Purcellville would not be of much interest today, among other things. As author Sittig’s tour this summer shows, they seem to have been mistaken. Let’s hope that’s so.

*Nancy Spannaus is a public historian and is the author of Hamilton Versus Wall Street, which can be purchased directly from the publisher at iUniverse (softcover or e-book). Her forthcoming book is entitled Why American Slavery Persisted.