By Edward Spannaus

In Part IV of this series, we learned how some of the tenants on the Tankerville lands in the eastern part of the German Settlement began to fight back against the abuses visited upon them by the Tankervilles’ land agents. This abuse often took the form of land agents seizing tenants’ personal property and selling it in order to collect claimed rent arrears. Some of the tenants brought legal actions against the Tankerville agents in court, but didn’t get very far. It wasn’t until 1789 that the tide began to turn, as we shall see in this installment.

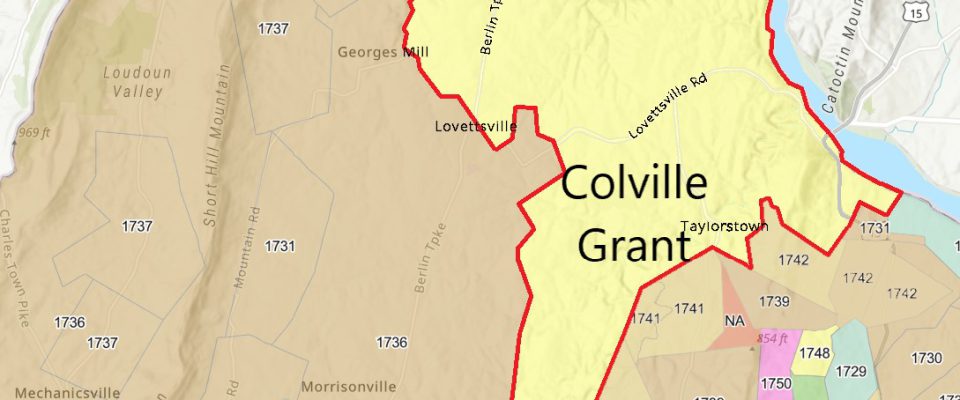

On the eve of the American Revolution the inhabitants of the area of northern Loudoun County – mostly Germans and Quakers from Pennsylvania – had almost no legal rights in the land they were occupying and farming. As with much of Virginia, the system of property ownership was modelled on the British manor system, with ownership in the hands of large planters or absentee landlords, and tenants being subject to the whims of the landowners with little or no legal protection.

Why did it take two decades after the Declaration of Independence for these industrious farmers to be able to own the land which they had improved and developed? Shouldn’t the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783 have given these family farmers the right to own property? Why did things actually get worse for these people for a couple of years after the Revolutionary War, before they started to get better?

To answer these questions, even in a preliminary fashion, has meant assembling information from a number of sources.

- First are the land records themselves, which are very sparse for the period before and during the Revolutionary War. This was where my curiosity was piqued for a number of years, when I noticed that land ownership among the settlers here seemed to take off around the year 1793. A number of leases and deeds, starting around 1789, cite judgments having been obtained by tenants, suggesting that they had been parties to court cases.

- This led to a frustrating search of court records, which consisted of two elements: (a) Order Books, which record judgments and orders of the court, usually in very summary fashion, and (b) what are called “Loose Papers,” the pleadings or the case files of individual cases. These are tiny pieces of paper (which was scarce in those days), many of which are missing, and sometimes difficult to decipher.

- Then there was the correspondence between the Tankervilles in England, their land agents in Virginia, and with political leaders such as George Washington and Edmund Randolph whose help the Tankervilles sought to deal with the sequestration and potential confiscation of their lands during the Revolutionary War.

- To understand how sequestration of Loyalist properties worked in Virginia, it was necessary to study this subject, including examining detailed financial ledgers of the Commonwealth of Virginia during the war. The Library of Virginia in Richmond was very helpful in identifying these records.[i]

How the leases came about

In the last installment we saw that legal actions brought by tenants did not fare very well in the courts. In addition to the couple of court cases we examined (from 1784 and 1787), we had land agent Robert Hooe writing to the Tankersvilles in 1788 that he had been successful so far in defending their property against both the threat of confiscation, and against lawsuits brought by tenants. Hooe had been advised behind-the-scenes by Virginia Attorney General Randolph, that the Tankervilles should sell their landed estates while they still could. But Hooe was complaining that he lacked the documentation to prove that the Tankervilles had the legal right to sell the properties, and he expressed increasing concern that the Tankerville interests were being damaged, perhaps irreparably.

In the late 1780s there were a number of tenant actions against the Tankervilles (or the Bennetts, as they are better called). But there were more cases brought against the tenants by the Tankerville agents.

In the Spring of 1789 (coinciding with the establishment of the new federal government led by George Washington), the Tankersvilles begin granting leases to their tenants. This begins on March 4, and by the end of 1789, Henry A. Bennett (the Earl’s brother), has granted leases to 30 tenants, generally for 100-acre tracts of land. On April 1, a long-term lease-for-lives is granted to Adam Wolf, one of the plaintiffs in the 1784 Chancery case we examined last month.

That’s what you find out from looking at the land transactions recorded in the Deed Books.

If you look at the court files (“the loose papers”), you see a sudden flurry of judgments –with cases being settled – in August of 1789. However, just from the case records, it’s difficult to draw any conclusions except that these cases involved some sort of compromise, with neither side getting everything they asked for. This in itself is a shift from the previous years.

The correspondence files shed a lot of light on this. On December 23, 1789, land agent Robert Hooe wrote a letter to Charles Bennett, the 4th Earl of Tankerville, expressing his alarm at the current state of affairs.[ii]

I am extremely concern’d at the disappointment in not receiving the several Papers I then wrote for, in as much as they are all indespensibly necessary in conducting the Business of Your Brothers Estate here, and for want of the Will in particular we have already experienced great inconvenience & loss too, and if it does not come to hand soon, I cannot say what may be the consequences resulting from the want of it.

So Hooe is complaining that they have been suffering losses in court for lack of documentation – most importantly, the Last Will and Testament of the 3rd Earl of Tankerville — and that it may soon get a lot worse. He goes on:

Ever since August Court last, when a number of Mr Bennetts suits was called for Trial we have been obliged to take them out of Court & Arbitrate upon Terms that we would never have Submitted to had not our Lawyers Advised us that no Action could be maintaind on the ground of the Copy of the Will in our Possession, because it was not Authenticated in the Proper Office for Probate of Wills in England.

Now we can see why so many cases came up in August, and we find out that Hooe and the attorneys felt compelled to submit these cases for arbitration, because they were afraid that they would otherwise be thrown out of court because they couldn’t prove clear title to the lands. This explains why these cases appear to have been resolved by a carefully worked-out compromise.

For example, the court files show Jacob Stoneburner confessing (acknowledging) a judgment against him of ₤40, but the final order was for ₤21.4.8. (Bennett’s agents had originally claimed ₤273 in rental arrears and had had the sheriff seize Stoneburner’s furniture and livestock.) In another case, Oliver McCaslin was discharged by a payment of ₤8.8, although he had confessed judgment for ₤20, and the land agents claimed ₤44 in back rents.

Hooe then makes a startling admission. Continuing to discuss the 3rd Earl of Tankerville’s Will, Hooe says that when they tried to prove his son Henry Bennett’s title to the land, the arbitrators were ready to throw the whole thing out.

And even before the Arbitrators, the instant we produced it to show Mr Bennetts title to the Estate, it was Struck at by the Tenants Attornies & declared by the Arbitrators to be of no validity for want of Authentication. This would have finished the whole Business at a single stroke, had we not there agreed that John West not only has a Power of Attorney but Admitted it to be legal, which we intended to deny, & with great Justice & truth we could have done, & saved too much thereby to lose by not doing so; for by doing this we have been forced to grant upwards of Thirty Leases under promises proved to have been made by him whilst Agent. Whereas his Power never was properly executed in England, nor Recorded in Virga.[iii]

So in order to avoid losing everything, they had to agree that John West had a legal power of attorney, which they were about to deny!

Why was this so important? Hooe is grousing that they were forced to grant 30 leases because of promises West had made. The horror of it all! Tenants who had been farming the land for 20 or 30 years were finally going to get formal leases which would be recorded by the court. The feudal land system was slipping away, but not yet entirely.

The Arbitrators’ Accounts

Two court orders – more detailed than most – issued in September and November 1789, explain what was happening here.

In September, in the case of Peter Holler (Haller, a German settler) against Bennett, the court ordered that where the tenants could show that a lease had been promised, by someone who was authorized to make such a promise, they would get a lease, and execution of a judgment against them would be stayed (stopped). It appears that Joshua Daniel and John Littlejohn were appointed as arbitrators, “with power to choose an umpire in case of disagreement” between them.[iv]

In reviewing the care records (“loose papers”), this writer was struck – and somewhat puzzled — by the neatly-drawn up statement of Accounts in most of the case files.

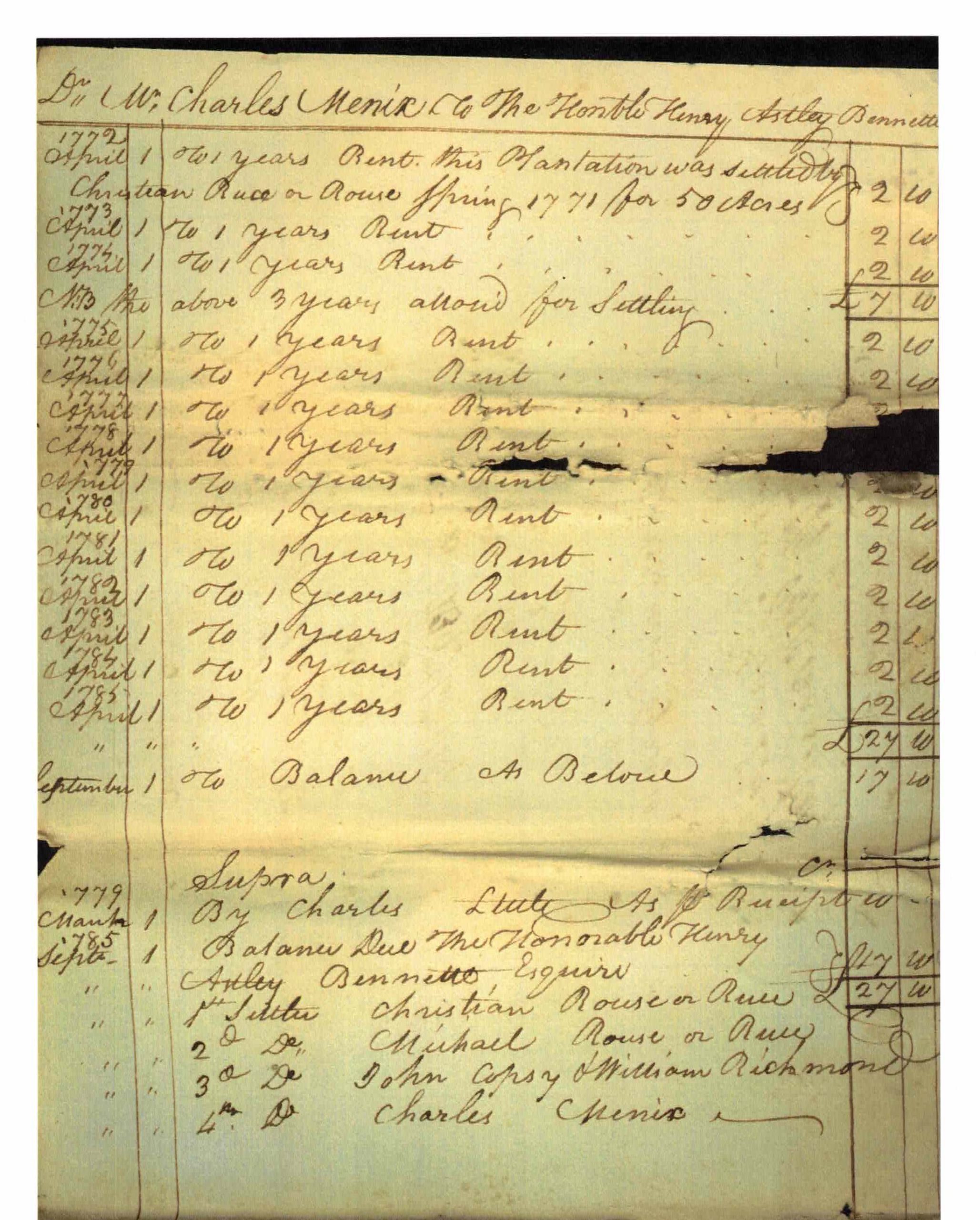

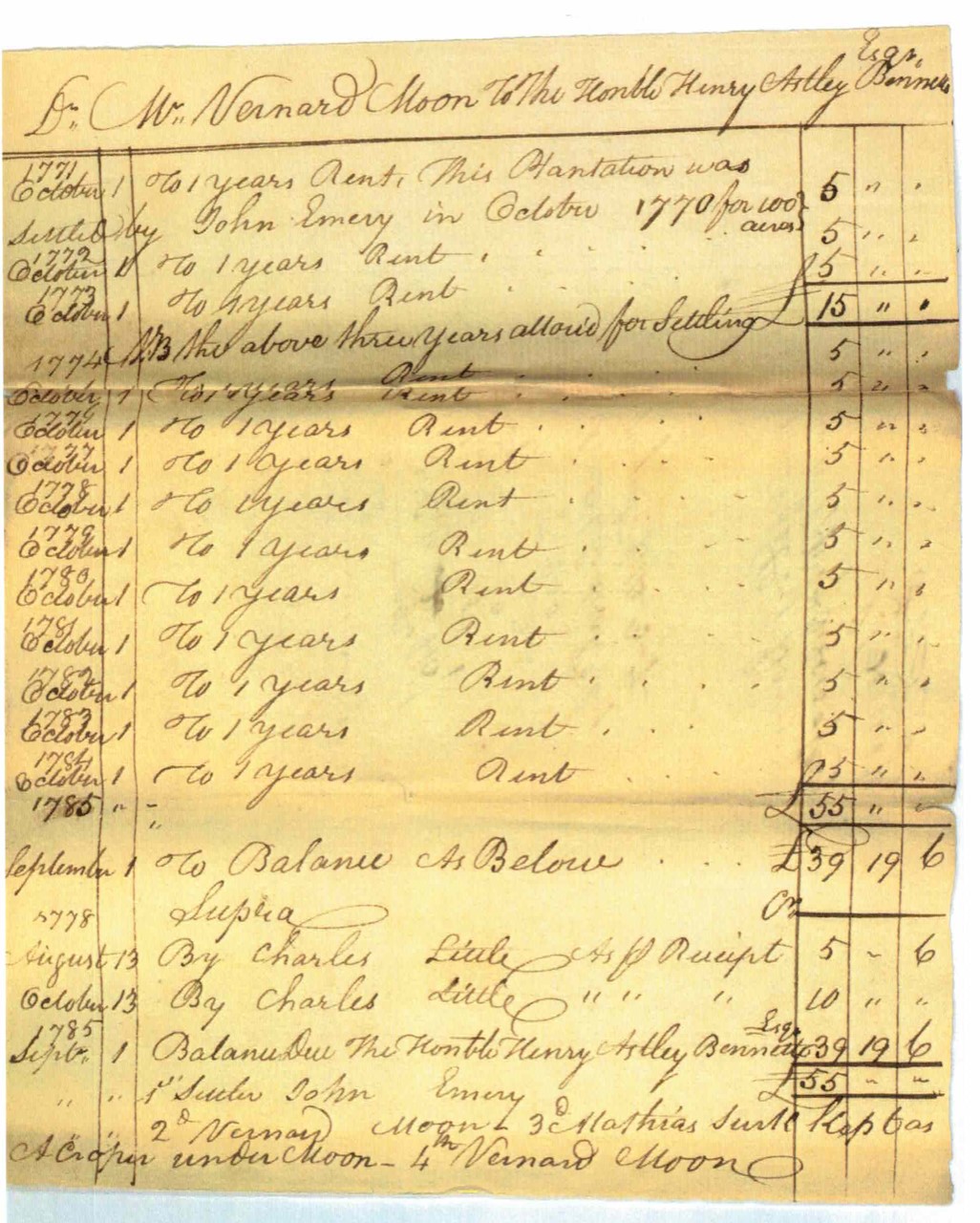

To take one example, the account of how much Charles Menix was alleged to owe to Henry Bennett. The statement begins by stating when the tract of land (or “plantation”) was settled. “This plantation was settled by Christian Ruse or Rouse, Spring 1771 for 50 Acres.” (Christian Ruse, a German settler, should be known to many of our readers.[v]) At the bottom, is a listing of settlers on that parcel of land: “1st Settler, Christian Rouse or Ruse; 2nd Michael Rouse or Ruse; 3rd John Copsy and William Richmond; 4th Charles Menix.”

Back at the top, after stating when the land was first settled, it lists three years rents, under the statement “above 3 years allowed for Settling” – in his case amounting to ₤7. Then 12 years, totaling ₤24, with a balance of ₤17 (subtracting the first three years). The it shows ₤10 “By Charles Little” in March 1779, which would refer to rent collected by Little to be paid into the State of Virginia sequestration accounts for Loyalist property. This adds up to a total of ₤27, with a ₤17 “Balance Due The Honorable Henry Astly Bennett, Esquire.”

These account statements are both interesting and curious.

- They list all the settlers on a particular tract of land, usually 100 acres, since the Tankervilles began seeking settlers for the land in the late 1760s. It seems like a fairly high turnover of settler/tenants, which might be expected when the tenants were “squatters” with no formal leases.

- They generally show rent collection by Charles Little in 1778-1779, when the Tankerville lands were sequestered as Loyalist property. These rents presumably made up part of the ₤1,219.42 that was paid into the State Treasury on May 13, 1779 on behalf of Henry Bennett.[vi]

- Some show additional rent collection by Little in 1783-84, although at this time Little would not have been acting as Commissioner for Sequestration, but simply as the Tankerville land agent.

- The assumption is that no rents were ever collected, except by Little, and that the current tenant was somehow liable for the entire balance due—although the arbitrators and the court did not seek payment of the full amount.

It may well be that the Tankerville/Bennetts did in fact not collect rents from many of their tenants. Hooe hints at this in the section of his December 1789 letter, quoted below. The allowance for three rent-free years for settling the land was set by the Arbitrators. The Tankervilles were probably more interested in owning the land itself, rather than in collecting rents. The tenants were expected to improve the land by erecting houses and barns, and by planting orchards and crops. This increased the land’s value, and, as we have noted, was a requirement under the land grants obtained from the Virginia colonial government.

Back to the Hooe letter, where he reports that the spate of litigation has forced them to conduct surveys of the land tracts, and how this has brought some order to what was “darkness and confusion.”

Since last Spring both Colo. Little & myself with two surveyors, Chain carriers &c at Catoctan & Louden County together have on the whole attended upwards of Eighty days in [determining] the outlines of the Land & the Lotts and Tenements & disputes within & frequently [we] have been obliged to have a number of Witnesses, generally two Lawyers & two Arbitrators with us, which has made the survey an expensive piece of Business, but there was no avoiding it for we have been obliged to fight our way thro’ Inch by Inch to get things so far Settled as they are, and altho’ not yet finished, yet we are happy to say we have reduced the greater part from out of darkness and confusion into System & order, and altho’ it has been done at a heavy expense, it has turned out a Profitable piece of Business to Mr Bennett. By disputing quarrelling, & Arbitrating we have at length recovered by Bond & Security & Money to the amount received, ₤3029.11.7 back Rents, many of which have been standing 27 Years unsettled.

What the Court decided

How this worked out, in this phase, can be gleaned from a long statement, dated 10 September 1789, apparently from the two Arbitrators, which was approved by the court and published in the Order Book for the court session in November, 1789.[vii] This order covered 13 tenants who had sued Henry Bennett and his bailiffs, and apparently was the template for many more in this phase.

The Arbitrators decided that three of the tenants (Holler, Cecily Minix, and Neis) were entitled to a lease for two lives, and nine others (Moon, Lambach, J. Stoneburner, Charles Minix, McCashland, DeSedorius, J. Grove, Weast, and Crook) were awarded only year-to-year leases. The Arbitrators noted that it was their decision to allow three years rent-free from the first settlement, and that they had fixed the rents at ₤3 per annum per 100 acres. Those not entitled to leases were assessed rents that the same rate as the others, except that after 1779 (a time of great inflation) the rents were ₤10/annum “until the time of making the distress” (i.e. the seizure of personal property) when all arrears were considered due. With respect to the payment of taxes, they said that they had “proportioned” the taxes for 1780 between the landlord and the tenants,

… and in the year 1781 we allowed each tenant the whole of the rent in consideration of the payments of the said taxes; on this we were governed by the Acts of the Assembly and the nature of the submissions, tho’ we thought it hard upon the landlord.

Interestingly, one of the arguments made by the lead tenant-plaintiff in this case, Jacob Grove (Groff), was to challenge whether Bennett, as a British subject, had the legal right to bring or maintain any action in the Virginia courts. Grove argued that:

Henry Astley Bennett is, and was at the time of the taking the goods and chattels, an alien born in the Kingdom of Great Britain under the ligeance of the King of Great Britain, and that he is … a Subject and under the ligeance of George the Third, King of Great Britain and as such is incapable of maintaining any real or mixed Action within the Commonwealth of Virginia …. Jacob prays for judgement and his damages by Occasion of the taking and unjustly detaining the said goods and chattels….

By this time, the Treaty of Paris had been ratified, which allowed for restitution to British property owners and for British creditors to seek payment of debts. However, Virginia was slow to recognize these provisions of the Treaty, which may be why Grove/Groff raised the issue in the Loudoun County Court.

We mentioned above that Adam Wolfe, one of the tenants who sued Bennett in 1784, did eventually get a formal lease, in April 1789.[viii] That award was based on the promise that was made by John West, who was mentioned in Hooe’s letter to Tankerville. The lease states that Adam Wolfe has obtained a judgment for the award of a lease for three lives, for 100 acres as promised to Moses Heaton (the prior tenant) by John West, agent for Charles, the 3rd Earl of Tankerville. In compliance with the judgment, Bennett is granting a long-term lease for the property, which was at that time occupied and being farmed by of Adam Wolfe.

A number of other promises made by John West are cited in the leases granted in August 1789, for example, to Devault Nies, Thomas Davis, and Peter Holler

The result of all this litigation, was that Henry Bennett was compelled to grant 30 leases in the year 1789, eight more in 1790, and the last one in 1791.

The Bennetts were still not selling land to their long-time tenants, but just leasing it under the semi-feudal system of lease-for-lives.[ix] How they finally did sell off their Loudoun County land holdings, bringing their piece of the British manor system to a close, will be the subject of our next and final installment.

[i] This included microfilm copies of the ledgers of the Auditor of Public Accounts, which showed all deposits, including sequestered land revenues, which went into the State Treasury. There is still much to be explored in these records and related records.

[ii] These letters were transcribed by the author and reviewed by a colleague. I have removed some of the cross-outs, and added some punctuation for clarity.

[iii] John West was John Colville’s son-in-law, who with Colville’s daughter Catherine had inherited 1000 acres of land under John Colville’s Will.

[iv] Loudoun County Order Book L, Grove v. Binns et al., 14 September 1789.

[v] Christian Ruse was owner for many years of the property that became Lovettsville Community Park. See article http://www.lovettsvillehistoricalsociety.org/index.php/the-ruse-family-a-typical-story-of-our-german-settlers/

[vi] Receipts of State Loan Office, compiled by Auditor of Public Accounts (APA 54, Vol. I, 1778-1787). This was also later stated in dollars as $4,064.72, in a report to the General Assembly in 1790.

[vii] Loudoun County Order Book L, 11 November 1789, pp. 305-307.

[viii] Lease for lives from Henry Bennett to Adam Wolfe, April 1, 1789, Loudoun County Deed Book R 373.

[ix] This description of the lease-for-lives system in the manors of northern Viriginia as “quasi-feudal,” was made by historian John T. Phillips II in The Historian’s Guide to Loudoun County, Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996). These types of leases, also known as “farm leases,” were generally for the lives of three named family members.