By Edward Spannaus

In Part III of this series, we “listened in,” so to speak, on discussions between the 4th Earl of Tankerville (Charles Bennett), his brother Henry A. Bennett, and their agents and attorneys across the Atlantic, in America. Their land agent, Robert T. Hooe, described his secret consultations with Virginia’s Attorney General and then Governor Edmund Randolph, and how Randolph advised then on how to try to prevent confiscation of the Tankerville Estates as Loyalist properties. In a 1788 letter, Hooe reported confidently that some legal actions against them had been quashed by the courts, but by the end of 1789, he was complaining that they were having trouble defending against some of the lawsuits brought by tenants. Worse, he lamented, they were being forced to grant leases to some of those occupying their lands.

In this installment, we will hear the tenants’ side of the story, as told in a couple of lawsuits, and we will learn about their claims of the abuses visited upon them by the Tankervilles’ agents.

It is obvious from the Loudoun County Court Order Books, and from land records, that there were a great many legal actions brought against the Tankervilles and their agents – and preceding those, many lawsuits brought by the Tankervilles and their agents against the settler/tenants and those who had been occupying their lands for many years, even decades. Unfortunately, few court documents from those lawsuits have survived.

We have been able to examine a couple of cases where documents can still be found. Both arose from actions taken by Charles A. Little, who was appointed as Commissioner to manage the Tankerville lands after they were sequestered under the March 1778 Act of the General Assembly against British and Loyalist properties. One such case, is a 1784 legal action against Charles Little brought by a Waterford Quaker, Samuel Schooley, and two German settlers, Adam Wolf and Thomas Davis. The other case was filed in 1787 by tenant Nathan Laycock.

Let’s listen to what these tenants had to say about how they were treated by the self-styled “Gentlemen” who were put in charge of the Tankerville lands by either the General Assembly or the Tankervilles themselves. (Charles Little was both: when he was appointed as Commissioner of the Tankerville Estates by the General Assembly, he had already been involved with the Tankerville lands and had worked with Robert Hooe. Such cronyism was typical of the manner in which sequestered and confiscated Loyalist properties were handled in Virginia during the Revolutionary War.)

The Schooley-Davis-Wolf case

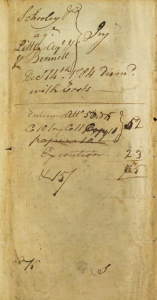

Schooley, Davis, and Wolf filed their action in the Chancery Court of Loudoun County on December 13, 1874.[i] A little background will be helpful in understanding this. Virginia, as had other colonies, inherited a dual court system from the English, with Courts of Law and Courts of Chancery. The Chancery Courts were intended to serve as courts of equity, created to remedy injustices rendered by a strict application of the Common Law.

The action brought by the plaintiffs in the Schooley case was effectively what we would call a “class action” today, since they were speaking of unjust actions that affected other tenants as well as themselves.

The major injustice of which these tenants complained, was that after the lands were sequestered in 1778, Commissioner Charles Little and William Ellzey[ii] had come onto the land which the tenants occupied, and demanded that they pay back rents to Little at inflated rates. When the tenants couldn’t pay immediately, Little seized the tenants’ personal property, and forced it to be sold. All of this was accompanied by threats and legal maneuvering.

Many of these tenants were essentially “squatters” without formal leases. The Tankervilles, as well as the Fairfaxes and other large landowners, wanted people to settle the lands and improve them, since under the original land grants (Culpeper, Fairfax, etc.), the lands had to be improved within a certain number of years, or they would be forfeited. These provisions were not strictly enforced, but for many of the landlords, having the land improved was more important than collecting rents – although at times they would do both.

Because many, if not most, of the settler/tenants on the Fairfax and Tankerville lands in northern Loudoun County did not have formal leases, they did not have any legal protection from arbitrary actions from the landlords. Schooley, Davis, and Wolfe stated that for those without leases, there was great uncertainty as to both the quantity of land they were occupying, and the amount of rent they were obliged to pay.

From other court actions brought by Tankerville, Bennett, and their agents such as Hooe, it seems clear that many of the tenants had not been paying rents regularly. One should keep in mind that the Revolutionary War years were a time of great hardship in Virginia, which was exacerbated by the runaway inflation of paper money. In the period after the Revolutionary War, and even during the last years of the War, there was an aggressive effort by the Tankervilles’s agents such as Hooe, to collect back rents—whether or not they had already been paid. This is what Little seems to have been doing, under the color of being a state-appointed “Commissioner.”

When Little and his assistants came onto the tenants’ lands and threatened the tenants if they did not meet their demands, the tenant/settlers were understandably frightened, and they made their best efforts to comply.

The Schooley complaint, really a petition to the Chancery Court, stated that these settlers, “being mostly Germans, unlettered men, unacquainted in the Law and Customs of this County,” tried to meet these demands in the best manner they could. They raised the funds from the sale of their horses, cows, and other property, and held the money until, “to their great surprise,” the legislature declared the money to be no longer lawful currency.[iii]

Nonetheless, Little continued to demand payments of arbitrary amounts of claimed arrears, “contrary to the known laws and usages of this State,” and he persuaded the courts to seize the tenants’ personal property, using the legal actions known at the time as “distraint” or “distress.”

Furthermore, the tenants said, they had wanted to get legal advice to show that the legal “distress” was “illegal, and contrary to justice and equity.” But they couldn’t find any lawyers, because Little and Hooe had already retained all the attorneys who practiced before the Loudoun courts!

The tenants then prepared to act “of our own accord” (what today we would call “pro se,”) and seek an order (a “writ of replevin”) from the court for the return of their seized property.

But Little attempted to intimidate them, by “menaces and threats,” to dissuade them from bringing an action, and he threatened that they would have to pay double damages if they proceeded to bring this action. But the tenants went ahead, asking the Court to keep in mind that they were unlettered men, acting without counsel. Their sense of urgency was driven by the fact that the appointed date was approaching for the distress sale of their personal property, by which they would be “greatly injured and oppressed.”

They also raised an interesting issue, of whether it would even be legal for them to pay the Tankervilles’s agent Charles Little, since, the tenants said, they had been informed that the General Assembly had passed an Act prohibiting the payment of British debts, and Little was of course acting on behalf of Henry Bennett, a British subject. During the war, under the Sequestration Act, revenues from sequestered properties were supposed to be paid into the State Treasury.[iv] However, with the war’s end, and the Treaty of Paris, the status of sequestered properties was unclear, and it seems that Little was now trying to collect rents and arrears aggressively for the direct benefit of himself and the Tankervilles – since no evidence has been found that Little paid any more monies into the Treasury after 1779.

The petitioners, noting they had no remedy under the strict rules of the Common Law, appealed to the Court of Chancery, asking the court to issue a subpoena to Little, so that he could be asked a number of questions which they spelled out. These included:

- Had Little been appointed by the State of Virginia, and under what authority was he acting?

- Was it under the State Government that he was continuing to act, or under what authority?

- Had he agreed with the tenants to have the lands surveyed, and was this ever done?

- Had he ever received any part of the rents during the period of paper currency? Where and when?

There were also a number of questions which implied that Little was taking advantage of those tenants who didn’t have leases, and charging them at a higher rate than those who did have leases.

The relief that the tenants asked the court to provide, was to compel Little and his agents to return the seized property to those from whom it had been unjustly taken, that all obligations created under the legal proceedings in the Common Law Court be declared void, and that all monies be returned to the tenants, so that they might be restored to the situation they were in “before these cruel seizures were made.”

They pleaded to the court to provide them with the benefit of the laws, of which they have been deprived by “oppression on one side, and ignorance and mistakes on the other.” They concluded by asking the Chancery Court to issue an injunction against Little and his agents from taking any further action until the matter could be fully heard by that court.

From the documents remaining, it appears that the case was quickly dismissed on the next day, December 14, 1784, and Schooley, Davis, and Wolf were charged with bearing the costs of the proceeding. It would be a couple of more years, before the tide would begin to turn and Tankerville’s tenants could successfully assert their rights.

Nathan Laycock’s case

More light is shed on Charles Little’s abusive practices by another Chancery case brought by one Nathan Laycock against Little in June 1787.[v] Laycock had purchased a lease from Col. James Hamilton on the property of the late Earl of Tankerville, at a rent of ₤3 per year, starting in 1766. But after the beginning of the (Revolutionary) War, Laycock had been charged for taxes, and he paid these taxes after being advised that his property could be seized if he didn’t pay them. He did this, even though under the terms of the lease, he wasn’t liable for any taxes or quit-rents.

After Charles Little was appointed Commissioner under the Sequestration Act, he starting coming around to collect rents. In April 1779, about a year after Little was appointed, he came to a settlement with Laycock, and gave him receipts for 11 years’ rents – which Laycock said he was prepared to produce in court. But even after reaching the settlement with Little, Laycock still paid the taxes on the land, for fear of being evicted.

On September 1782, Little sent a certain George Muir around to collect rents from the tenants on behalf of Henry Bennett. Laycock paid, and was given a receipt.

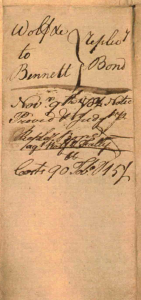

Despite everything that Laycock had paid, in March 1783 Deputy Sheriff John A. Binns, at the direction of Little, made “distress” (i.e., seized his personal property) upon Laycock for upwards of ₤39. Laycock posted a (replevin) bond for the whole amount of the distress. Little acknowledged that he had distressed Laycock for more rent than would have even been due had Laycock made no payments or advances after the April 1779 settlement.

As Laycock described it, Little pretended that he would give Laycock credit for what he had already paid, and would only take a judgment for what was actually due. But instead, he combined (i.e. conspired) with diverse persons and obtained a judgment against Laycock for ₤22.8, with interest.[vi] This included all the rent arrears which Little pretended were due. Plus, Laycock had greatly overpaid the amount of taxes due on the land, because he was told (wrongly) that he was compelled to do so.

Charles Little didn’t give Laycock credit for any of the amounts he had already paid, but instead he threatened to execute the judgment on Laycock’s personal property immediately. All of Little’s actions “are contrary to equity and good conscience,” Laycock asserted in his complaint.

As Schooley et al. had done previously, Laycock then set forth a series of questions about which the Chancery Court should interrogate Little. These pertained to the amount of rent and taxes which Laycock had already paid, whether Little had given Laycock any credit for these payments, the circumstances of the distress against Laycock, and so forth.

Laycock asked the Court to enjoin Little from proceeding to execute the judgment against him–except for a small amount of interest which Laycock had agreed that he owed–and he requested that the Court should issue a subpoena to Little so he could be questioned by the Court.

With the Treaty of Paris now signed and ratified, and the federal Constitution under consideration, the courts seemed to be looking more favorably upon tenants’ complaints than they did in the Schooley case a few years earlier. The Chancery Court appears to have reached a compromise. Shortly after Laycock filed his action, the Court did grant his request for an injunction against Little, barring Little from proceeding with the distress sale of Laycock’s personal property. But Laycock was required to post a bond.

The case was continued (postponed) for over two years, by which time public sentiment had apparently further shifted. In early 1790 the case was settled, with Laycock paying costs, but without his property being sold. From scanning other similar cases, this seems to have been the pattern by this time. (Those court papers which still exist are tiny pieces of paper, with even smaller handwriting which is often indecipherable to the modern reader.)

In our final installment next month, we will look at the changes in landlord-tenant relations, and how the feudal manor system was abolished—even though it took over a decade after the end of the Revolutionary War, to complete this process.

[i] Samuel Schooley et al. vs. Charles Little, Agent. In Chancery, Loudoun County 1784-001, M-7060. Available at Library of Virginia website, and Loudoun County Clerk of Court, Historic Archives Division.

[ii] Wiliam Ellzey was, among other things, a Virginia State Senator from Loudoun County.

[iii] This may be a reference to the action of the General Assembly in late 1781, when it abolished highly-depreciated paper money (“Continentals”) as legal tender, and issued a new currency.

[iv] Little and Hooe did pay ₤1,219.42 into the state treasury on May 13, 1779. No further payments have been found.

[v] Nathan Laycock vs. Charles Little, agent for Henry A. Bennett. In Chancery, Loudoun County 1790-015, M-1359. Available at Library of Virginia website, and Loudoun County Clerk of Court, Historic Archives Division.

[vi] It appears that this judgment of ₤22.8 was re-issued on April 10, 1787, in the case styled Bennett vs. Laycock and Myers.