A Discussion of the Historic Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court Ruling against School Segregation and Its Result in Loudoun County

By Nancy Spannaus*

Approximately 60 Loudoun County residents gathered at the historic Black Douglass High School in Leesburg, Virginia on April 13, to hear a panel discussion on the battles around school desegregation in Virginia and the role of the judiciary, especially the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court. The event was hosted by the Edwin Washington Society [1] and the Loudoun Douglass Alumni Association, and kicked off by Larry Roeder, founder of the Society and co-author of the recent book on Loudoun County fight for desegregation Dirt Don’t Burn. That book, as Roeder explained, draws on the records of the fight by parents and teachers in Loudoun for an equal education for Black children, which are reflected in hand-written petitions and other documents unearthed at the Loudoun County public schools and various other locations.

The title “Dirt Don’t Burn” comes from a 1955 letter from a teacher to the Board of Education, in which she pointed out that her “colored school” had no coal with which to heat the building. We are “down to dirt, which doesn’t quite burn,” she wrote, and we need coal. (She got it.)

Roeder opened the meeting with an overview stressing the heroic struggle of often overlooked men and women to fight for a quality education for Black children. “Our kids deserve better,” they argued, while marching and petitioning for funds and adequate facilities. In the late 1930s, the Black community in Loudoun formed the County-Wide League which proceeded to raise the funds to buy land for the building of an accredited high school. As a result of legal as well as political pressure, the Loudoun County School Board finally agreed to build and fund the school in 1941 – after insisting that the League transfer the land to them for $1!

Following Roeder, Alumni Association president and Douglass graduate Charles Avery gave a brief description of the Association and its activities, and his own experience growing up under “separate but equal.” Avery had to ride a bus 18 miles every day to Douglass, which was the only high school available to Black students until the courts finally got compliance from the County to desegregate in 1968. But “you don’t know what you don’t know until you know it,” he commented. And while he didn’t know what he might be missing by not going to a better-funded, integrated high school, he noted that the students at Douglass enjoyed small classes and young energetic, highly committed teachers.

The panel discussion and audience participation that followed not only proved highly educational, but reflected the intense involvement of many audience members in this issue. A substantial number of attendees were Black and old enough to have experienced segregated education; younger members of the audience, white and Black, were more focused on what they saw as today’s parallels to the backlash against desegregation which occurred especially in Virginia, as well as how to combat it.

Clearly, such events – oriented, in Roeder’s words, to fostering a non-partisan conversation on this complex subject – can provide opportunities for healthy discussion and debate. With the 70thanniversary of Brown v. Board of Education coming up May 17 of this year, the time is ripe for such education and dialogue.

The Legal Battle for Desegregation

Event Chairwoman Lisa O’Donnell, a past president of the Virginia Trial Lawyers Association, opened the panel discussion with a detailed review of the history of the road from “separate but equal” (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896) to the Brown v. Board of Education’s ruling that such treatment was unconstitutional (1954). Her detailed description, summarized below, was clearly enlightening to many in the audience.**

Access to public education was highly uneven throughout the United States in the antebellum period, and in the Southern states like Virginia, did not even get going until after the Civil War. Crucial in spurring an expansion of public education to Black children in the South were the Reconstruction Era amendments to the Constitution, which outlawed slavery, defined citizenship, and banned racial discrimination in voting. The key was the 14th Amendment, which promised “equal protection under the law” and “due process of law.”

But in 1896, the Supreme Court made a decision which was used to undercut those principles for decades. The case at issue was brought by a Louisiana man of mixed race, Homer Plessy, who had the nerve to sit in a whites-only car on a train. After he was arrested and convicted, Plessy eventually appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing for “equal protection under the law.” The Court ruled against him, claiming that segregation was okay as long as Blacks were given “equal” accommodations.

Civil rights lawyers fought a losing battle against segregation during the following decades but in the early 1950s, decided to turn their attention to desegregating K-12 education. The chosen case was that of 6-year-old African American Linda Brown in Topeka, Kansas, who was denied the right to attend her neighborhood school due to her race. Her father decided to press the issue and take it to the top.

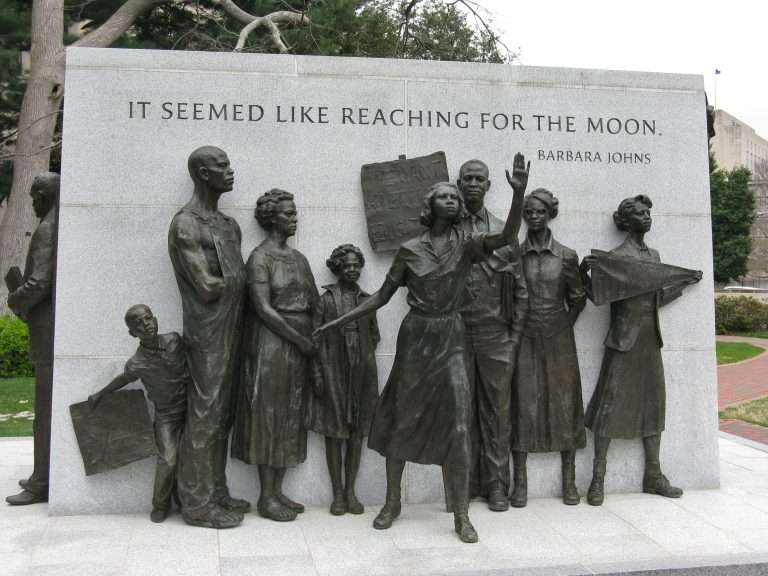

Brown’s challenge to school segregation was not the only one in process. Even more dramatic was that in Prince Edward County, Virginia where teenager Barbara Johns courageously launched legal action for desegregation after calling a student strike. Johns was spurred to act by the death of a friend, which was due to the fact that her school bus (a dilapidated reject from the white schools) had broken down on the railroad tracks. Ultimately, Johns’ case, along with others in Delaware, D.C., and South Carolina, were combined with Brown’s to bring the issue of the constitutionality of school segregation to the Supreme Court in 1953.

As O’Donnell described it, Chief Justice Fred Vinson delayed a decision that year in the interest of gaining more unanimity, but then died, leaving it to President Eisenhower to appoint a new Chief Justice. Ike appointed Earl Warren, who was determined to rule for the plaintiffs, but also took his time in order to get a unanimous decision, in hopes of preventing the opposition from taking advantage of a division. He succeeded in getting the former.

Brown v. Board of Education made two key statements, O’Donnell said. First, it asserted that education is the most important function of state and local governments. Second, it declared that “separate but equal” violates the 14th Amendment since it made education inherently unequal (as could be easily empirically verified). Since the decision declared no timetable, it was followed up in 1955 with what is called “Brown II,” which mandated that desegregation occur “with all deliberate speed.”

The Panel Discussion

Three panelists then commented on the consequences of the Brown decision.

Professor Danielle Wingfield, an assistant professor of Law at Richmond University Law School, honed in on the Massive Resistance movement which was spawned in Virginia in reaction. Wingfield, who was born in Prince Edward County, cited her grandparents’ inability to go to school during the 1959 to 1964 period when that county shut down the public school system in order to avoid court-ordered integration. Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd coined the term Massive Resistance and urged actions to get around the legal orders. Wingfield concluded by saying that she saw a resurgence of massive resistance today in the rulings against affirmative action and in the school choice movement.

Alexandria civil rights attorney Chris Brown picked up the narrative about the organizing of Massive Resistance. It began with Governor Thomas Stanley, under whose tenure Virginia passed a plan which provided funds for schools that refused to desegregate, and, in its final iteration, defunded schools which integrated. Meanwhile U.S. Senator Harry Byrd was organizing broader resistance, ultimately getting more than 100 Southern Congressmen (82 Congressmen and 19 Senators) to sign a “Southern Manifesto” in 1956, which called Brown an infringement upon Constitutionally guaranteed states’ rights, andurged resistance to forced integration “by any lawful means.”

Public schools were closed in many areas of Virginia, in accordance with the Stanley plan. When the Virginia Supreme Court invalidated it in 1959, the opponents of desegregation turned to “freedom of choice” programs which led to many white students leaving the public schools which were integrated. This policy was ultimately crippled with the 1968 Supreme Court decision in Green v. New Kent City (Virginia). Green set up new standards for desegregation, which vastly accelerated the process in the southern states.

It was a long struggle, Brown commented, noting that efforts to overturn Plessy v. Ferguson had begun in earnest in the 1930s. It’s critical for citizens to get involved in the fight, and vote.

The final panelist was Nathan Bailey, a volunteer for the Edwin Washington Project who has specialized in documenting the transportation system for the Loudoun County public schools from 1870 to 1968. Bailey chronicled the growth of the bus system, and its operation during segregation, showing its obvious disparity. His work was based in part on interviews with drivers, some of whom were students who had gotten their licenses and taken on the job.

Sharing the Stories

The last part of the meeting featured contributions from the audience as well as additional stories from the panelists. O’Donnell, for example, reviewed the case of the racially motivated prosecution of basketball star Allen Iverson, which she successfully overturned in the courts. Roeder recounted some egregious examples of discrimination, emphasizing the courage of those who challenged the racism. One woman in the audience described a circumstance at a local high school which showed that racial discrimination is still a problem today.

Of particular note was the intervention of Gladys Burke, a Loudoun entrepreneur, who grew up in an all-Black community in South Carolina, and experienced her elementary education mostly under segregation and high school under desegregation, but at a Black-dominated school. To the surprise of some, Burke strongly asserted her view that she received an excellent education, one that left her totally confident in the company of those educated in Ivy League schools. Burke’s view was reinforced by two other speakers who also went to segregated schools.

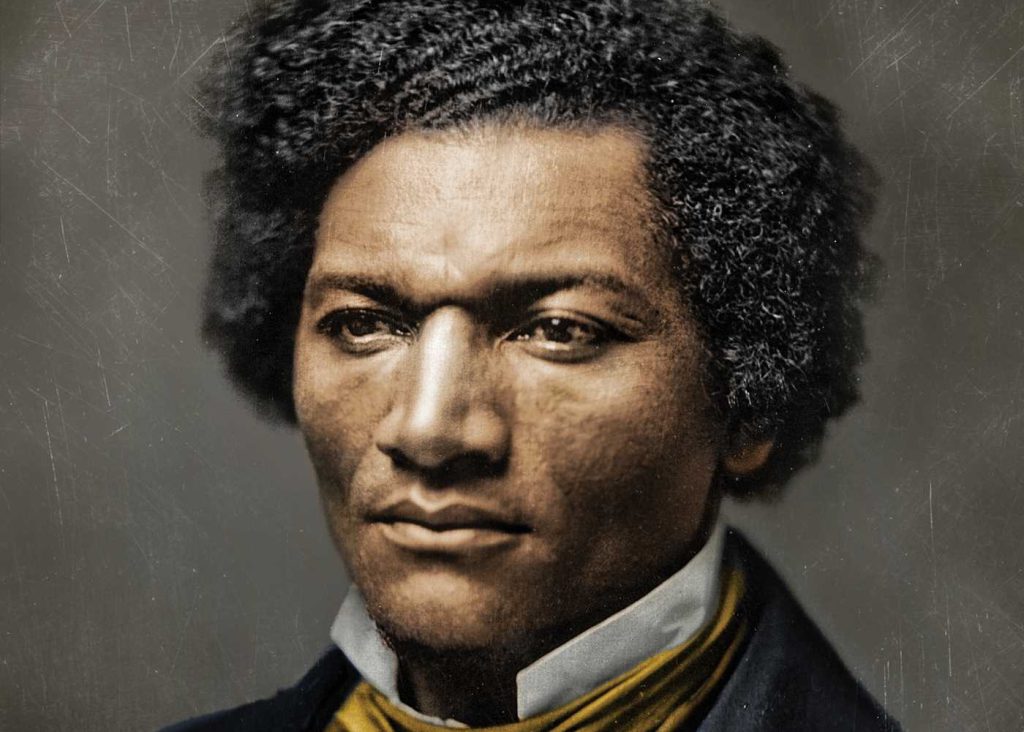

These statements led me to make the following observation: Could it be that students in the all-Black schools under segregation, despite the material deprivations, benefited from the stronger commitment to the value of education expressed by their teachers and the community? The fierce determination to fight for an education, as expressed by civil rights hero Frederick Douglass, gave those children a cultural advantage which is often not shared in white-dominated schools where the right to an education is taken for granted.

I noted the comments of former Virginia Supreme Court Justice Charles Thomas, made at the recent Virginia250! Conference which I attended, on the difficulty of getting Black youth to engage with history.[2] They are taking their current rights for granted, he said, as opposed to those of us who had to fight to obtain those rights. I then added that Frederick Douglass himself put extraordinary value on education, noting in his Autobiography that “Knowledge unfits a man to be a slave.”

The meeting concluded with some closing remarks by Roeder, who emphasized the complexity of the issue, and by his co-author, Barry Harrelson. Roeder then invited attendees to share in refreshments, and to purchase Dirt Don’t Burn. Judging from the animated discussion both during and after the event, it is clear that such opportunities for education and dialogue are highly appreciated. Fortunately, a video of the event will shortly be made available by the Society.

*Nancy Spannaus is the author of Defeating Slavery: Hamilton’s American System Showed the Way, available here.

** I apologize in advance for any factual errors, as I am writing from notes, not a transcript.

[1] The Edwin Washington Society is a non-profit dedicated to documenting the history of the fight to desegregate Loudoun County schools. It takes its name from a young African American, who, in 1866, was so determined to get an education that he took the unusual step of negotiating with his employer to get the time to be able to go to school, even while maintaining his job.

[2] See my post on this event here.